Tilar J. Mazzeo’s “The Hotel on Place Vendôme” – Hôtel Ritz in Paris: June 1940 (excerpt)

24 Thursday Apr 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures

Tags

Alsace France 1940-1944, Ardennes France, Belgium World War II, Bordeaux France World War II, Calude Auzello, Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, Cesar Ritz, Charles de Gaulle, Clara C Piper Associate Professor of English Colby College Tilar J Mazzeo, Coco Chanel, Ernest Hemingway, First World War, France, France in Second World War, Frank Meier, Georges Mandel, German Rhineland World War II, Hanz Franz Elminger, Harper's Bazaar, HarperCollins Publishers, Hermann Göring, Holland World War II, Lost Generation, Luxembourg World War II, Maginot Line, Maine, Manhattan, Marie-Louise Ritz, Nazi occupation World War II, New York Times, New York Times bestseller list, Operation Valkyrie, Paris, Paul Reynaud, The Hotel on Place Vendôme Life Death and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in Paris Tilar J Mazzeo, The Hotel Ritz in Paris, The Occupation of Paris 1940-1944 Ritz Hotel, The Secret of Chanel No 5 by Tilar J Mazzeo, The Widow Clicquot by Tilar J Mazzeo, Third Reich, Vancouver Island British Columbia, Vichy regime France World War Two, Winston Churchill, World War II

Share it

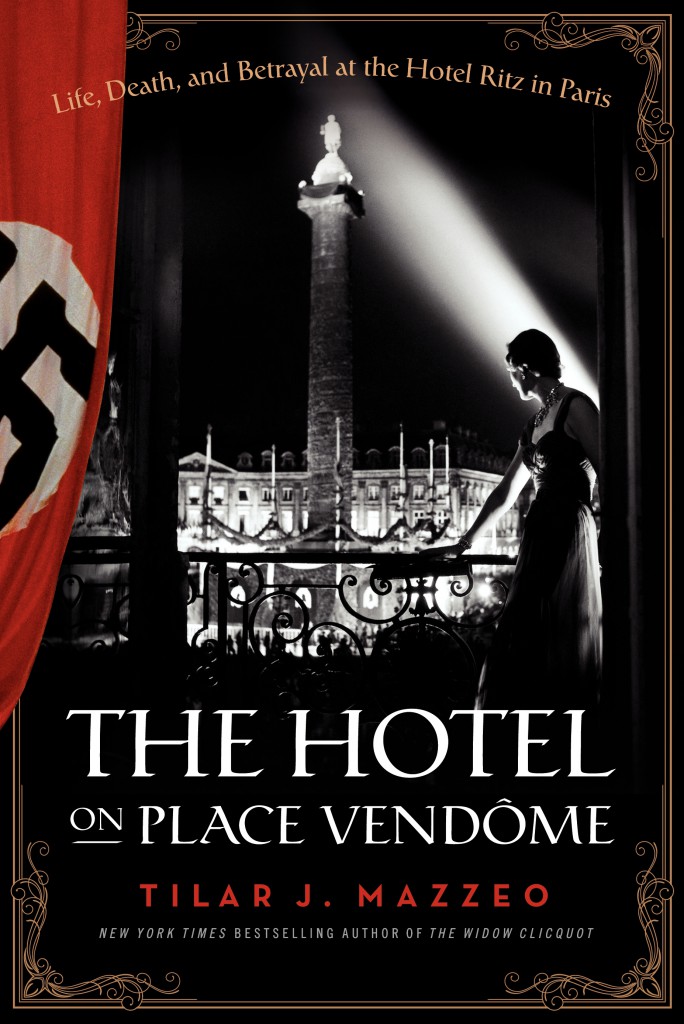

Excerpt from The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris by Tilar J. Mazzeo ©2014 Tilar J. Mazzeo. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Excerpt from The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris by Tilar J. Mazzeo ©2014 Tilar J. Mazzeo. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Since opening its doors in 1898, Paris’ Hôtel Ritz has epitomized world-class luxury and incomparable glamour while serving as a favorite destination for royalty, statesmen, movie stars, and Lost Generation writers among others. But what is less known about this lavish establishment is the high-stakes drama that played out within its fabled walls during the German occupation of France in the Second World War.

When France fell in June of 1940, Berlin decreed that unlike other plush properties, which were simply commandeered by the Germans, the extremely symbolic Ritz would remain operational. So, the French capital’s most iconic hotel was divided in half and began housing the Nazi elite alongside its usual rich, famous, and infamous clientele. This legendary landmark quickly became the city’s epicenter of intrigue—both in its grand public spaces and in its secret areas—and a place where some lives were saved, others were betrayed, and many were forever changed.

Told in vivid detail and with gripping immediacy, The Hotel on Place Vendôme introduces a sprawling cast of characters that includes actors, intellectuals, artists, aristocrats, socialites, Vichy politicians, spies, double agents, and Germans officials as well as the hotel’s staff and owners. Chronicling the lifespan of the occupation, Mazzeo produces a thrilling narrative that spotlights the activities of notable residents such as Hermann Göring, the obese, drug-addled air force general who spent countless hours amassing a priceless collection of looted art when not running Hitler’s war machine, and Coco Chanel, who closed her fashion house and lived with her German lover for the duration of the war, and influential figures like Frank Meier, the one-quarter Jewish bartender who was involved in the resistance, and Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, the military commander of occupied Paris and a key player in the failed Operation Valkyrie.

Chapter One: “This Switzerland in Paris–June 1940” by Tilar J. Mazzeo

For anyone looking at a map of France, that breach to which de Gaulle refers lies where the borders of the Alsace and the Lorraine jut sharply into the German Rhineland. To the north rest the low-lying countries of Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg. To the south rise up the Alps and the mountain state of Switzerland.

By 1939—after ten years of disastrously expensive construction and the hard-won lessons of the First World War—the French had built, along that boundary from Luxembourg to Switzerland, a barricade against a dark future: a series of formidable steel-and-concrete fortresses known simply as the Maginot Line, named after the general who planned them.

Those fortifications, however, also had a fatal weakness. At the northern edge of the French border, to the east, lay Belgium, and that deep and friendly frontier remained largely unprotected. Nowhere were the fortifications lighter than where the border ran along the dense forestland of the Ardennes. It was considered impenetrable. In a matter of days in May 1940, a million German soldiers proved that it was not.

With fearsome speed that spring, the forces of the Third Reich swept through the Low Countries and into France. Their object was the citadel at the heart of the country: the storied capital city of Paris.

And for many of the high-ranking German officers, who were no more immune to the enticements of legend than the rest of their generation, the Hôtel Ritz was already at the heart of Paris. Since the end of the nineteenth century, this palace hotel on the spacious Place Vendôme in the city’s first arrondissement, or “district,” had been an international symbol of luxury and all that was glamorous about modernity, home to film stars and celebrity writers, American heiresses and risqué flappers, playboys, and princes. The 300,000 Germans who would soon occupy the city would live in Paris not just as an army and as bureaucrats but also as tourists, many of whom wanted nothing more than to be delighted with the pleasures of this famously beautiful metropolis.

Before the war had even begun, the Hôtel Ritz had already been at the center of political action on the Continent and was shaping this century. The German arrival would change nothing about that. Winston Churchill had visited the hotel not once but twice in the weeks before the Germans skirted the Maginot Line. In fact, immediately after delivering at mid-month his first radio broadcast as Britain’s prime minister—in which he conceded that “[i]t would be foolish to disguise the gravity of the hour”—he headed straight to Paris for a crisis meeting of the supreme war council with his French counterpart, Paul Reynaud. At the end of the month, on May 31, 1940, Winston Churchill came again, this time to see if there was any way France could survive the westward onslaught.

Winston Churchill always preferred to stay at the Hôtel Ritz. “When in Paris,” Ernest Hemingway once quipped, “the only reason not to stay at the Ritz is if you can’t afford it,” and Winston Churchill, the son of an English lord, had never been short of resources.

With the Germans on the march that spring, there was one old friend that Churchill especially wanted to talk things over with. He and Georges Mandel, the Jewish-born French minister of the interior, had talked things over like this many times in the last decade, when, together in the political wilderness of the 1930s, they had warned their countrymen that the unfettered rise of a nostalgic German nationalism would have terrible consequences. Their predictions had been sadly accurate.

Georges Mandel, however, didn’t just stay at the Hôtel Ritz occasionally. He had lived in darkened rooms on the fourth floor full-time since the mid-1930s. The Hôtel Ritz had among its numbers in those days at least a dozen permanent residents, none of them obscure or powerless.

Some of those residents would soon be leaving. By June 11, 1940, with German troops within thirty miles of the city, a collective panic swept through Paris. The French government fled the capital overnight and decamped to Bordeaux, in the southwest of the country. The railway system ground to a halt only a few hours later. Over the radio the next afternoon came an order for all the men in the city to leave the capital to prevent their capture. Rumors flew about the brutality and sadism of the advancing German soldiers, and no woman relished being left behind as a war trophy in a fallen city.

In the mass exodus that followed, a full 70 percent of the city’s population—close to two million people—took to the highways, hauling their possessions and their infirm relatives behind them in an effort to flee the German advance, joining a stream of refugees from Belgium and Holland. But it was already hopeless. They would turn the roads heading south into a colossal traffic jam. Most would never make it more than a hundred miles beyond Paris.

The Hôtel Ritz was not immune to the panic. By June 12, 1940, for the second time since the battle for France had begun, the German air force, the fearsome Luftwaffe, was pounding the city of Paris with incendiary bombs, and a siege seemed inevitable. The hotel’s newly promoted director, an old French soldier named Claude Auzello, had been called up for military service, and his American-born wife, Blanche, had followed him to his posting in Provence. His deputy director, Hans Franz Elminger, the nephew of the hotel’s most important aristocratic investor, however, was Swiss—and the Swiss, of course, were famously neutral. So that week it was left to Hans Elminger, along with the elderly Marie-Louise Ritz, the Swiss widow of the hotel’s eponymous founder, César Ritz, to chart a course for the cast of characters who inhabited this luxurious refuge. The next few days would require deft diplomacy and all their combined efforts.

Praise for The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris

“Must read… Mazzeo artfully transports readers to the Nazi occupation of World War II… The Hôtel on Place Vendôme contextualizes the opulence of 1940s Paris, making for a work of history that reads as enticingly as a novel.” —Harper’s Bazaar

“Tilar J. Mazzeo tells the tale of the Hotel Ritz, a landmark so imbued with glamour that it was the only hotel in Paris the Nazis ordered to stay open during the war. The antics at and around it during World War II were often shocking.” —New York Post

Tilar J. Mazzeo is a cultural historian and biographer, and the author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, The Secret of Chanel No. 5, and nearly two-dozen other books, articles, essays, and reviews. The Clara C. Piper Associate Professor of English at Colby College, she divides her time between coastal Maine, Manhattan, and Vancouver Island in British Columbia. (Website)(Facebook)(Twitter)(Purchase)(A Woman’s Paris Interview with Tilar J. Mazzeo)

Tilar J. Mazzeo is a cultural historian and biographer, and the author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, The Secret of Chanel No. 5, and nearly two-dozen other books, articles, essays, and reviews. The Clara C. Piper Associate Professor of English at Colby College, she divides her time between coastal Maine, Manhattan, and Vancouver Island in British Columbia. (Website)(Facebook)(Twitter)(Purchase)(A Woman’s Paris Interview with Tilar J. Mazzeo)

Photo credit: Sarah Rose

Selected Books by Tilar J. Mazzeo

The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris. Harper, March 2014, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

The Secret of Chanel No. 5: The Intimate History of the World’s Most Famous Perfume. Harper, November 2010, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It. HarperBusiness, October 2009

A Woman’s Paris® is a community-based online media service, bringing fresh thinking about people and ideas that shape our world and presents a simplicity and style, in English and French.

Connecting with you has been a joyous experience—especially in learning how to enjoy the good things in life. Like us on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter. Share us with your friends.

Barbara Redmond

Publisher

barbara@awomansparis.com

Text copyright ©2014 Tilar J. Mazzeo. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

Photography copyright ©2014 Sarah Rose. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com