John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “MANY FÊTES”: The Hôtel du Cap and Tender Is the Night (excerpt)

15 Wednesday Jul 2015

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures

Tags

Alice Terry, Antibes France, Archibald MacLeish, Art Literature Love Life Côte d'Azur France, Cannes Film Festival, Charles Brackett, Cole Porter Begin the Beguine, Donald Ogden Stewart, Duke of Windsor King Edward VIII England, E Phillips Oppenheim, Elsa Maxwell, Ernest Hemingway, Étinne de Beaumont, F Scott Fitzgerald Tender is the Night, F Scott Zelda Fitzgerald, French art, French culture, French Riviera and Its Artists Art Literature Love and Life on the Côte d'Azur John Baxter, French Riviera Hotel du Cap, General Charles de Gaulle Hôtel du Cap, Gerald Sara Murphy, Hôtel du Cap French Riviera, James Gordon Bennett Hôtel du Cap French Riviera, Jean Cocteau, Josef von Sternberg, Joseph Kennedy, Le Figaro Hippolyte de Villemessant, Le Train Bleu Jean Cocteau, Lescure France, Marlene Dietrich, Mediterranean, Mistinguett, Natacha Rambova, Pablo Picasso, Paris, Rex Ingram, Rudolph Valentino, Save Me the Waltz Zelda Fitzgerald, Tender is the Night Dick Diver F Scott Fitzgerald, Tender is the Night Scott Fitzgerald, Three Soldiers John dos Passos, Villa du Soleil Côte d'Azur, Wallis Simpson, Winston Churchill, World War I, World War II

Share it

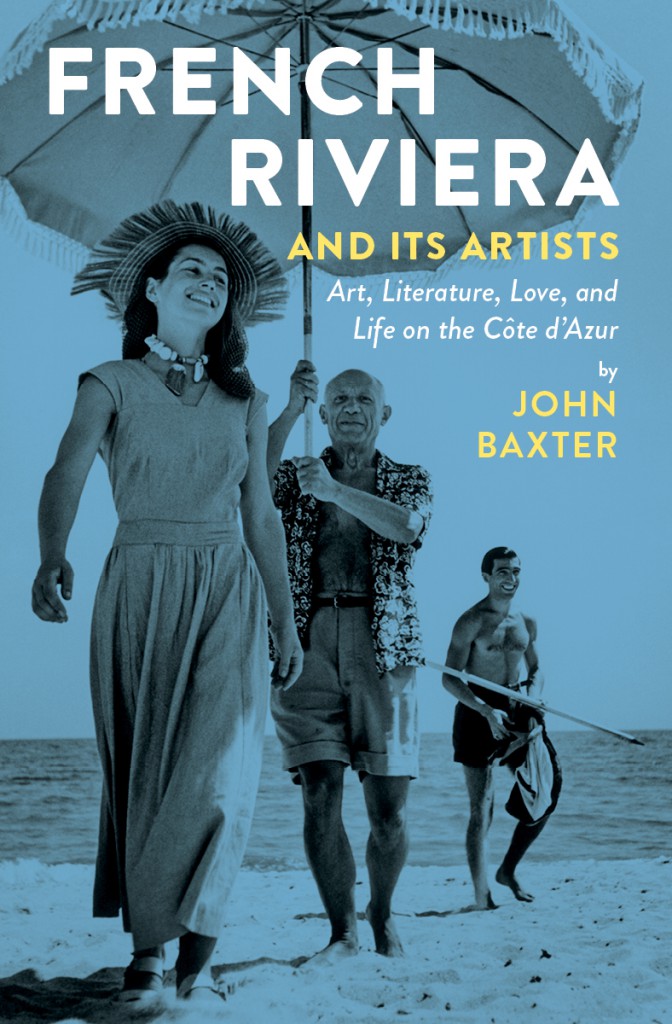

Excerpt from French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur – “MANY FÊTES”: The Hôtel du Cap and Tender Is the Night (excerpt), by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Museyon. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur – “MANY FÊTES”: The Hôtel du Cap and Tender Is the Night (excerpt), by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Museyon. All rights reserved.

Get swept up in the glitz and glamour of the French Riviera as author and filmmaker John Baxter takes readers on a whirlwind tour through the star-studded cultural history of the Côte d’Azur that’s sure to delight travelers, Francophiles, and culture lovers alike.

For jesters and armchair travelers alike, French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur is sure to become an instant classic and will make even the most dedicated home-bodies yearn for the land of cafés and literary greats. (July, 2015, Museyon) (Purchase)

Praise for French Riviera and Its Artists

“These luminaries celebrated life and created art amid paradise and this book is the ultimate guide to the Riviera’s golden age.” —Christine Gray, luxurytravelmagazine.com

“As with all Museyon guidebooks, the volume is richly illustrated: The back matter alone features an art gallery of the French Riviera and its artists, but paintings are interspersed throughout the book.” —June Sawyers, Chicago Tribune

Subscribers, French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur by John Baxter bestselling author of The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, and We’ll Always Have Paris. Free book giveaway to two subscribers ends July 15, 2015.

Free Subscription: Join our thousands of followers to receive your copy of our Readers’ Choice: 253 Books About France, including books about Architecture, Interiors and Gardens; Arts; Biography; Children; Culture; Fashion; Food and Wine; Memoir; Mystery; Novel; Science; Travel; and War, along with email notifications of new posts on the website.

Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. We never sell or share member information.

Excerpt: John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”: Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir published with permission by A Woman’s Paris®.

Excerpt: John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “PABLO PICASSO”: In a Season of Calm Weather… (excerpt) published with permission on A Woman’s Paris®.

Interview: French Impressions: Author John Baxter and Editor Janice Battiste – conversations of the evolution of the book, “French Riviera and Its Artists” on A Woman’s Paris®.

French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur (excerpt)

“MANY FÊTES”:

The Hotel du Cap and Tender Is the Night

by John Baxter

“On the pleasant shore of the French Riviera, about half way between Marseille and the Italian border, stands a large, proud, rose-colored hotel. Deferential palms cool its flushed facade, and before it stretches a short dazzling beach. Lately it has become a summer resort of notable and fashionable people.”

Scott Fitzgerald was right to begin Tender Is the Night, the finest of all Riviera novels, with this description of the Côte d’Azur’s most exclusive hotel. He calls it Gauss’s Hotel des Etrangers—the Hotel of Foreigners—but the name, like the beach, is a fiction. Disdaining the democracy of sand, guests at the Hôtel du Cap swim in a heated saltwater pool hewn from the granite of the headland, its water replenished with each wave that crashes on the rocks.

The founder of the newspaper Le Figaro, Hippolyte de Villemessant, built the Villa du Soleil in 1869 as a refuge for authors suffering from writer’s block. As successful writers didn’t need such a place and the unsuccessful couldn’t afford it, his plan flopped. In 1889, he reopened the villa as a simple hotel, named Hôtel du Cap. At this it also failed. Visitors to the Riviera came to see and be seen, not to doze in seclusion. Business dwindled until the staff of forty served a mere two guests—a pair of elderly English ladies who paid the minimum rate of twelve francs a day. Each morning, the manager sent a horse-drawn omnibus to the railway station in hopes of new clients, but it invariably returned empty.

The hotel was rescued by American newspaper-owner James Gordon Bennett, who wanted a place for his recently widowed sister to grieve and recover in peace. Rather than bother with weekly bills, he slapped down 40,000 francs and told the proprietor to let him know when that was used up. (The principle of accepting payment only in cash became a tradition. Until the early 2000s, the Cap refused credit cards.)

Bennett’s intervention persuaded the hotel to promote seclusion as an asset. Where better for a crowned head to relax incognito, a celebrity to enjoy a holiday untroubled by fans, or an illicit couple to consummate a clandestine liaison? The approach to the hotel through a private wood guaranteed secrecy, while deep water just offshore and a dock at the base of the cliff allowed passengers to debark from their yachts with a stealth impossible at the Carlton.

Privacy, however, only went so far. In 1903, Lord William Onslow, a regular guest, was being taken to the station by the owner when they fell to discussing the hotel’s lack of central heating, elevators, and en suite bathrooms. Before he boarded the train, Onslow bought the hotel outright and ordered the necessary improvements.

After renovations, occupancy rose, and with it the rates. In 1914, the hotel added its outdoor pool. A second building, the Eden Roc pavilion, at the very tip of the headland, provided an indoor pool and restaurant. In addition, thirty-three private cabanas appeared along the cliff edge and among the umbrella pines. These semi-permanent huts with couches and bathrooms, available only by day and intended as places to change before and after a dip, quickly assumed other functions. Jean Cocteau’s 1924 ballet Le Train Bleu tipped a knowing wink when it showed illicit couples slipping away into similar hideaways for a little afternoon delight.

Although the hotel originally closed from May to October, it began cautiously to extend its season after wealthy expatriates Gerald and Sara Murphy, house hunting in the area, persuaded the owners to keep one wing open through the summer of 1923. Once F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald rented a villa in nearby Lescure, they hung out at the hotel, which became an informal clubhouse for sun-birds. Not that its amenities saw much use. “At the most gorgeous paradise for swimmers on the Mediterranean,” lamented Fitzgerald, “no one swam any more, save for a short hangover dip at noon.” For the Fitzgerald/Murphy set, a hangover came with the territory. If you weren’t behaving badly, you weren’t doing it right. In Tender Is the Night, Dick Diver yearns for the dramatic squalor of a “bad party, where there’s a brawl and seductions and people going home with their feelings hurt and women passing out in the cabinette de toilette.”

Among the first celebrity guests was General Charles de Gaulle, who spent his honeymoon there in 1921. As word spread of this trendy new holiday spot, more artists and movie people drifted in. “That summer there was no one in Antibes,” wrote Fitzgerald drily, “except…” and here he reeled off a list of illustrious names: film-star Rudolph Valentino and his choreographer wife Natacha Rambova; director Rex Ingram with wife and star Alice Terry; crime novelist E. Phillips Oppenheim; cabaret queen Mistinguett; poet Archibald MacLeish; Hollywood writer Charles Brackett; socialite Étienne de Beaumont; novelist John Dos Passos and humorist Donald Ogden Stewart, both returning from having run with the bulls in Pamplona in company with Ernest Hemingway. “Just a real place to rough it,” concluded Fitzgerald ironically, “to escape from the world.”

It was at the Hôtel du Cap that Zelda Fitzgerald exhibited the first signs of her accelerating slide into bipolar disorder. After a dinner party, she would demand that Scott drive her there, and, stripping off her evening gown, dive near-naked into the ink-black sea. Scott followed, but gingerly—more proof to her of his dubious virility.

Further to taunt him, she began an affair with a flier from the air base at Fréjus. (“He was bronze and smelt of the sand and sun,” she wrote in her autobiographical novel Save Me the Waltz. “She felt him naked underneath the starched linen. She didn’t think of [her husband]. She hoped he hadn’t seen; she didn’t care.”) The night the affair ended, Zelda overdosed on sleeping pills. Called to the hotel by a frantic Scott, the Murphys took turns walking her for hours until the effects of the drugs wore off.

The stock market crash of 1929 drove most American expatriates back home. Abandoning his ambition to paint, Gerald Murphy returned to New York to resume control of the family business. After an abortive attempt by Zelda to train as a ballet dancer, the Fitzgeralds too went back home, where Zelda was hospitalized with schizophrenia. Scott’s epitaph for those lost Riviera summers, Tender Is the Night, appeared in 1934. While dedicated to the Murphys in recognition of their generosity and hospitality (“Gerald and Sara—many fêtes”), the novel depicted a couple who, though superficially resembling them, exhibited a tormented sexual and psychological history closer to that of the Fitzgeralds. Gerald was philosophical about the book but Sara saw it as the worst kind of betrayal.

The Americans might have left the Riviera but the fashion to spend summers on the Côte d’Azur was firmly established. Now it was Picasso and Cocteau who visited the Hôtel du Cap, leaving sketches in its guest book. Winston Churchill visited to relax and indulge his hobby of painting. The Duke of Windsor (the former King Edward VIII of England, who gave up the throne to marry American divorcee Wallis Simpson) stayed there with his new wife while they shopped for a villa.

It was late in the 1930s before Americans returned in numbers, and for a year or two life on the headland reverted to the golden days of a decade before. Few seasons were more glittering or dramatic than the summer of 1939. Among the hotel’s guests that June were film star Marlene Dietrich and Joseph Kennedy, the former movie mogul recently appointed U.S. ambassador to Britain. Kennedy and Dietrich continued the affair they’d begun the year before in the anonymity of its cabanas. At a party thrown by socialite Elsa Maxwell, Dietrich also ensured that her lover’s twenty-one-year-old son John would always remember the occasion. As she and the future president of the United States danced to the year’s big hit, Cole Porter’s Begin the Beguine, she slipped her hand into his trousers.

Reality intruded with the arrival from Berlin of Dietrich’s director and lover Josef von Sternberg. He brought embassy gossip of an impending non-aggression pact between Germany and Russia. Cutting short his holiday, Kennedy and family hurried back to London. Stalin and Hitler signed their pact on August 23. On September 1, Germany invaded Poland. Once the war moved into France, the Nazi-backed puppet government made the Hôtel du Cap its Riviera headquarters.

Having ridden out the occupation, the hotel received a transfusion of customers with the relaunch in 1946 of the Cannes Film Festival. The influx of wealthy foreign celebrities reinforced the air of distinction. Privacy became an even more potent selling point. Reporters never got past the front gate and aliases were standard—all signifiers of an old-fashioned snobbery that clients relished. Always impressed by “notable and fashionable” people, F. Scott Fitzgerald would have approved.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, and Five Nights in Paris. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, and Five Nights in Paris. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

Since moving to France, John has published biographies of Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Josef von Sternberg, Robert De Niro, and the author J.G. Ballard. He has also written five autobiographies, including A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. His most recent books are Chronicles of Old Paris and The Paris Men’s Salon, a selection from his uncollected prose pieces. John’s translations of Morphine, by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest and Fumée d’Opium, by Claude Farrère, have also been published by HarperCollins, the latter as My Lady Opium.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker at universities and writers workshops. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the internet in search of new acquisitions.

In 1974, John was invited to become a visiting professor of film at Hollins College in Virginia, U.S.A. While in the United States, he collaborated with Thomas Atkins on The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, a highly successful book of scientific speculation, and wrote a study of director King Vidor, as well as completing two novels, The Hermes Fall and Bidding. (Facebook) (Website)

Photo: Rudy Gelenter

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”: Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir (excerpt). Graphic artist, playwright, poet, novelist, film director—Jean Cocteau was too multi-talented for his own good. In a period characterized by commitment and specialization, his contemporaries scorned his failure to join some movement or embrace a cread. Cocteau felt himself to be above petty categorizations. He preferred to echo Oscar Wilde, who, on being asked by U.S. Customs if he had anything to declare, is said to have replied, “Only my Genius.”

John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “PABLO PICASSO”: In a Season of Calm Weather… (excerpt). In 1959, fantasy writer Ray Bradbury published the short story In a Season of Calm Weather. It describes an enthusiast for Pablo Picasso who visits the Riviera in hopes of meeting him. Walking on the beach one evening, he does indeed run into the artist and watches in wonder as Picasso, using nothing but a small stick, idly scratches a riotus frieze of nymphs and satyrs in the wet sand. But his delight has a downside…

French Impressions: Author John Baxter and Editor Janice Battiste – conversations on the evolution of the book, “French Riviera and Its Artists”. “Writers interviewed by the media or at festivals often describe the crucial moment they decided to write a book,” writes John Baxter. “In my experience, such moments seldom exist.” John never set out to write a book about the French Riviera and its artists. The idea caome from a New York publisher, Akira Chiba, who owns a small company called Museyon. Akira handed editing of the book to a trusted collaborator, the free-lance editor Janice Battiste. Janice and John had worked with great congeniality on The Golden Moments of Paris, so it was a pleasure for them to set out again. The extracts from John and Janice’s emails synopsize the process by which they jointly brought The French Riviera and Its Artists to a successful conclusion.

“Not All Here” by Paula Butturini – A peripatetic American ex-pat finds that the familiarity of “home” is always slightly out of reach. Perhaps it’s the sea changes in American life that explains Paula Butturini’s unease. Who sent our factory jobs to the developing world while I was gone, our secretarial and administrative jobs to customers’ home computers? Whe did the poisonous party politics replace public discourse? Butturini returned to the United States in 2015, and after more than three decades away, where she lived and worked in London, Madrid, Rome, Warsaw, Berline and Paris.

The Art Diaries: From Paris to Bretagne (part one) by Lilianne Milgrom. An artist and writer, Lilianne Milgrom is Paris-born, grew up in Australia, lived for extensive periods in Isreal, and currently resides in Washington D.C. A Winter’s Diary was written during her recent trip to Paris where she curated an exhibition at Saint-Germain des Prés, followed by an extended stay in Dinan as artist-in-residence under the auspices of Yvonne Jean-Haffen Museum. The Art Diaries, first published on AWomansParis.com, are excerpts from her journal A Winter’s Diary.

Travel Diaries: Two for the Road – Paris’s Line 2 (small-scale adventures on the Right Bank), by Rachel Rixen. By following the arc of the métro’s line two that cuts through the heart of the right side from west to east, Rachel sets out to catch a coup d’œil of her northern neighbors in the places that make them feel at home. The sun is hard to come by in Paris’s fall and winter months and any occasion to conveniently forget a beat-up umbrella is reason enough to go on a small-scale adventure.

Travel Diaries: Missing your train (in Paris): C’est la vie by Parisienne Bénédicte Mahé who shares stories of missing your train as a result of accidents on the railway due to animals, strikes or the weather—plus other practical ways of getting around France. Including websites to travel by trains in France.

Summer in Paris: a guide to surviving a heat wave (and still have fun). Parisienne Bénédicte Mahé shares how she survives the city with basically no wind, and how she escapes a very warm apartment to enjoy the many parks, open-air swimming pools, lakes with row boats, markets, public libraries, open-air movie theaters, and adds a South of France feeling with a pastis! Included are links to activities for children and adults.

Text copyright ©2015 John Baxter. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

1 comments

Jacqueline Bucar said:

July 15, 2015 at 5:24 am

Wow! If walls could talk…well actually they are! Baxter at his best, bringing his literary tours of Paris to the Riviera. But did the hotel really think it could make it when it originally closed between May and October? Next summer when I’m in Les Issambres for a wedding, I will definitely take a short detour to Nice and walk by the Hotel du Cap with a knowing wink.