French Impressions: Tilar J. Mazzeo’s “The Hotel on Place Vendôme” – 1940s sex, parties and political intrigue at the Ritz in Paris

29 Tuesday Apr 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Cultures, Interviews

Tags

Alan T Marty MD Paris City of Light, And the Show Went On by Alan Riding, Clara C Piper Associate Professor of English at Colby College Tilar J Mazzeo, Coco Chanel Ritz Paris World War II, Dreaming in French by Alice Kaplan, Emile Zola Dreyfus Affair Paris, Ernest Hemingway Ritz Paris 1944 Liberation, European Union, France, Harper's Bazaar, HarperCollins, Herman Goring World War II, Hotel Ritz Paris, Hotel Ritz Paris 1898, How Paris Became Paris by Joan DeJean, How the French Invented Love by Marilyn Yalom, Liberation of Paris 1944, Molecular Gastronomy by Herve This, National Archives in Washington, New York Post, New York Times, Occupation in Paris, Out Stealing Horses by Per Petterson, Paris, Paris 1940 - 1944 World War II, Paris at the End of the World by John Baxter, Pierre Laval World War II, Place Vendôme Paris, Second World War France, The Hotel on Place Vendome Tilar J Mazzeo HarperCollins, The Secret of Chanel No 5 by Tilar J Mazzeo, The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt, The White Album by Joan Didion, The Widow Clicquot by Tilar J Mazzeo, University of California at Davis, Unlikely Collaboration by Barbara Will, Vichy regime France World War II, W Scott Haine Simone de Beauvoir World War II

Share it

Tilar J. Mazzeo is a cultural historian and biographer, and the author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, The Secret of Chanel No. 5, and nearly two-dozen other books, articles, essays, and reviews. The Clara C. Piper Associate Professor of English at Colby College, she divides her time between coastal Maine, Manhattan, and Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

Tilar J. Mazzeo is a cultural historian and biographer, and the author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, The Secret of Chanel No. 5, and nearly two-dozen other books, articles, essays, and reviews. The Clara C. Piper Associate Professor of English at Colby College, she divides her time between coastal Maine, Manhattan, and Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

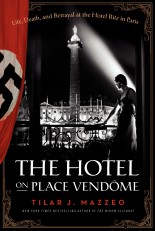

For over a century, the Hôtel Ritz has stood in the heart of Paris as a world-renowned symbol of opulence and modernity. A gathering spot for the rich and celebrated, this grand palace in the Place Vendôme is legendary—and yet a vital piece of its past remains shrouded in secrecy.

Now in The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris, is a riveting account that spans from 1898 to the present day, New York Times bestselling author Tilar J. Mazzeo uncovers the remarkable experiences of those who lived in the hotel during the German occupation of Paris, revealing how what happened in the Ritz’s corridors, palatial suites, and basement kitchens shaped the fate of those who met there by chance or assignation, the future of France, and the course of history. For more information about Tilar J. Mazzeo visit: (Website) (Facebook) (Twitter) (Purchase)

Now in The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris, is a riveting account that spans from 1898 to the present day, New York Times bestselling author Tilar J. Mazzeo uncovers the remarkable experiences of those who lived in the hotel during the German occupation of Paris, revealing how what happened in the Ritz’s corridors, palatial suites, and basement kitchens shaped the fate of those who met there by chance or assignation, the future of France, and the course of history. For more information about Tilar J. Mazzeo visit: (Website) (Facebook) (Twitter) (Purchase)

Excerpt from The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris by Tilar J. Mazzeo ©2014 Tilar J. Mazzeo. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Photo credit: Sarah Rose

“Tilar J. Mazzeo tells the tale of the Hotel Ritz, a landmark so imbued with glamour that it was the only hotel in Paris the Nazis ordered to stay open during the war. The antics at and around it during World War II were often shocking.” —New York Post

“In The Hotel on Place Vendôme, [Mazzeo] pulls back the heavy curtains of the Ritz in Paris to reveal a steamy world of sex, drugs, partying and political intrigue.” —Alan Riding, author of And The Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris

“Must read. . . . Mazzeo artfully transports readers to the Nazi occupation of World War II . . . The Hôtel on Place Vendôme contextualizes the opulence of 1940s Paris, making for a work of history that reads as enticingly as a novel.” —Harper’s Bazaar

INTERVIEW

The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the HôtelRitz in Paris

Since opening its doors in 1898, Paris’ Hôtel Ritz has epitomized world-class luxury and incomparable glamour while serving as a favorite destination for royalty, statesmen, movie stars, and Lost Generation writers among others. But what is less known about this lavish establishment is the high-stakes drama that played out within its fabled walls during the German occupation of France in the Second World War.

When France fell in June of 1940, Berlin decreed that, unlike other plush properties, which were simply commandeered by the Germans, the extremely symbolic Ritz would remain operational. So, the French capital’s most iconic hotel was divided in half and began housing the Nazi elite alongside its usual rich, famous, and infamous clientele. This legendary landmark quickly became the city’s epicenter of intrigue—both in its grand public spaces and in its secret areas—and a place where some lives were saved, others were betrayed, and many were changed forever.

“Of course, great hotels have always been social ideas, flawless mirrors to the particular societies they service.” —Joan Didion, The White Album, 1979

AWP: You are the author of The Hotel on Place Vendôme. What inspired you to write this book?

TM: I became fascinated by the story of the Ritz in Paris while researching my earlier book The Secret of Chanel No. 5. Coco Chanel, of course, spent the Second World War living in the Ritz with her German boyfriend. At one point I discovered in some files an incredible history of espionage at the hotel and decided to tell the story of what happened there during the occupation.

AWP: On at least one occasion you were warned that you should not attempt to tell this story. What was this warning and by whom?

TM: At one stage in my research, I was fortunate enough to speak with an elderly French woman whose husband had been senior in the resistance. I tell the story of that encounter in the prologue to the book, and she had warned me that trying to tell the history of what happened in Paris during the occupation would be incredibly difficult, in part because people had such powerful reasons for misremembering or forgetting.

AWP: How did this warning influence your book, The Hotel on Place Vendôme?

TM: It was a very useful warning as my research continued, because as she promised information was often hard to come by, people often were reluctant to talk, and sometimes the files were at odds with each other. In the end, the only records that one could trust were the archival materials. In the case of Blanche and Claude Auzello, for example, the German police files show clearly that they were suspected of acts of resistance. This lends credibility to their own claims about their actions—corroborates those claims, as it were. In other cases, people claimed to have been part of the resistance (or others claimed they were collaborators, conversely) but there is no record to support the story. In those cases, a historian needs to tread very carefully and acknowledge the impossibility of knowing for certain.

AWP: Your research is exemplary. How did you accumulate and obtain this information? From civil and court records, memoirs, letters, eyewitnesses, among others? Was the information primarily in French? What were the challenges and how did you uncover these stories?

TM: This book was intensively researched, and the materials were variously in French, German, and English. I conducted oral history interviews with a number of people and with the family members of some of the “characters” in the book, but most of the sources were from the National Archives in Washington, London, and Paris, from the police archives in Paris and Berlin, and from archives for Parisian history and Jewish history. Fortunately, those who lived at the Ritz during the war weren’t trying to hide the fact of their celebrity in many cases. They had their photos taken in Paris, sent letters, left journals. The hardest part of writing the book actually was organizing all the information, because it was a sprawling network of people, whose lives touched upon each other sometimes over a period of years.

AWP: During your research for The Hotel on Place Vendôme, what aspect of Paris’ history—from the years just before the occupation to the present—wouldn’t you include?

TM: Although this book has a chapter on the opening of the Ritz in 1898 and a chapter on the First World War, those are both prefatory to the real story here—the story of 1944 and 1945 in Paris. Of course one needs to set the stage and explain not only how the Ritz came into being but also how it became “The Ritz,” the legend. And there were lots of other stories about the earlier years of the war I could have told. But in 1944, the year of the Liberation of Paris, so many stories were reaching their climax that it was the perfect moment to focus on. I like to think of this book, after all, as not just a story of the Ritz and of the war but also as a biography of Paris as a city, from a very particular perspective and lens.

AWP: You have great insights into human nature and the sublime experience of social connectivity; a theme that runs throughout your book. What is the most surprising thing you learned about the Parisians? The Germans? The Americans?

TM: Yes, social connectivity and the ways lives are shaped by accidental encounters were two of the most fascinating themes that emerged for me in this book. The other theme I thought a lot about in writing the book was the question of neutrality—not just the forced “neutrality” many Parisians caught up in the city during the war struggled with but the neutrality as well of the Americans, the Swiss, the photojournalists, and of course myself as an historian. The most surprising things I learned—or perhaps “relearned”—about each of those countries had to do with the pressures of neutrality, in a way. I was surprised over and over again by how decidedly partisan and cruel the Vichy government was at moments. I was also surprised, on the other hand, by the stories of the small handful of Germans who didn’t act like so many of their compatriots. The story of the sexual tensions between the Americans and the French civilians after the war, I must say, was a bit shocking.

AWP: At times you intimately describe the selling of dreams—the dream of fitting in, the notion that if you dined at the right tables, rubbed shoulders with the right guests, people might indeed look at you in a new way. How do you unfold this story of transformation from the beginning of the occupation to its end?

TM: In many ways, what it means to fit into a society or a social circle is how the Ritz began for those who were drawn to it in 1898. It might not have been the Ritz, of course. It could have been some other space. But in the end, for reasons of chance in some cases, the Ritz became long before the 1920s the place in Paris where the vision of “modernity” in France and in the French arts and culture came together for a group of people who went on to become famous. Later, after the war, that story continued and the hotel was always the place where you went if you want to be part of everything that was “ritzy.”

AWP: Sociability, conviviality—was there an art to fitting in at the Ritz?

TM: The Ritz in the first decades and into the war was the chosen home of the artists, film stars, and bohemian socialites. There has always been something just a bit cutting edge about the circle that gathered there. The art of fitting in at the Ritz was to have one’s own vision and to be just this side of daring about it.

AWP: What were the rituals and rhythms of life at the Ritz?

TM: Of course there was tea in the garden, and there were Frank’s cocktails in the bar. Frank was a consummate barman and invented any number of cocktails for clients—something that is still a Ritz tradition. Hemingway wrote longingly about the quiet rooms “on the garden side” of the hotel, which were his favorite. His tradition was always Perrier Jouet champagne, but then of course champagne is always a Ritz tradition.

AWP: During the early years of the occupation, did many writers, philosophers and artists believe they were framers of a new era? Do we know their shared “truths”? Were they caught in their own web of self-proclaimed “genius” or did they see themselves as historical interpreters, thereby influencing events around them?

TM: One of the reasons the book begins with the opening of the Ritz in June of 1898 is because it’s so important what is going on at the same time in Paris: the second trial of Emile Zola in the Dreyfus Affair. That moment was a rupture in French society between the traditionalists and the modern-looking intellectuals, and those who took up the Ritz most passionately were the innovators of the capital. They were part of a movement that was sweeping Europe and North America at the turn of the twentieth century, and I think their “truths” were those we have come to recognize as distinctly modern—the idea of women’s independence, of the artist and intellectual as a voice of political conscience, of the surreal as the truest form of realism, of sexual liberation and class mobility, and of a certain kind of artistic meritocracy that energized the last century in so many ways.

AWP: How descriptive were the writings of common life on the streets and in the cafés and the goings on around them by writers and philosophers, in particular?

TM: There are a great number of letters, journals, memoirs, and so on where people describe life on the streets of Paris in wonderful detail. Those materials are the source for the atmospheric descriptions in my book. Because it’s narrative nonfiction, nothing is invented, and everything is drawn from some source that I found.

AWP: Collaboration is a serious charge: a term, as you write, that belongs in a black and white world. How do we understand the term collaboration in the grey-zone of life in France during the occupation? Were there subtle difference in the ways people of Paris interacted with their Nazi occupiers?

TM: Indeed, collaboration is a very sensitive subject. I was extremely cautious about making the suggestion anyone had collaborated unless there were clear written records and documentation to support even the suggestion. If someone was investigated after the war as a collaborator, for example, then it’s just a historical fact to say they were suspected of collaboration. There’s no ambiguity. Or if they wrote, as some people did, memoirs or books attempting to explain why their helping the Germans or the Vichy government didn’t seem like collaboration to them even though it seemed that way to their community, then that record of their involvement was also a historical fact. Pierre Laval, for example, wanted to claim that he was not guilty of collaboration at the end of the war—but in the end the French post-war government didn’t accept those claims and the documentation shows that he played a clear role in the deportation of Jewish children in France. In some cases, like these, the shades of grey aren’t very deep. In other cases, those shades of grey are nearly impenetrable. Was having a German boyfriend, for example, collaboration? Was waiting on Hermann Goring’s table at a café collaboration? Was neutrality a kind of collaboration? These are very difficulty and painful subjects in France. For me, the most important parts of this book are the new stories of the courageous staff members at the Ritz (and some of the guests too) he struggled with those risks and with the problems of neutrality and decided to help another person.

AWP: How have you been able to find a way of telling this story so that what people feel isn’t hatred or despair, but the larger sense of the fragility of life?

TM: That’s a good way to put it—the “fragility of life”—that’s very much what this book is about. It isn’t a book meant to make the reader feel hatred or rage, though of course it’s sometimes impossible not to be angry reading any history of the Second World War and impossible not to condemn so much of what was allowed to happen. But what I wanted to think about in this book was how complicated it is to be human and to face the ethical demands of our humanity, especially at a moment when so many things are conspiring to encourage people to remain aloof, to turn a blind eye to the plight of others. The risks of helping another, after all, were sometimes monstrous.

AWP: You are making some very interesting discoveries about Paris during World War II through research. Are you finding an underlying message that is especially significant for us today?

TM: One of the things I learned in the course of writing this book was how profoundly the Second World War shaped the history of the European Union’s development, and there are ways in which some of those tensions remain very much with us. I found that very interesting to consider.

AWP: The Hôtel Ritz in Paris has been closed for renovation and will reopen its doors in July 2014. During the renovation, did you find interesting discoveries among its corridors, palatial suites, and basement kitchens?

TM: We’re all eagerly awaiting the reopening of the Ritz, of course. I haven’t seen the renovation work—they are keeping it quite a secret—but we already know that there have been amazing discoveries, like the Le Brun painting authenticated in the Chanel suite. That was quite a surprise for art historians.

AWP: What was the most surprising thing you learned about the war from the writer-historian’s distance of nearly seventy-five years at its start?

TM: Not long ago, I read the book Indigniez Vous (“A Time for Outrage” in English), by the recently deceased Stephane Hessel, which of course was a bestseller in France. In that book he talks about his time in the French resistance and in a camp during the war, and he shared his thoughts on exactly this question—what we need to remember about how the Second World War began and the conditions that fostered it. I was quite moved by that book, and I must saying the story of the Ritz during the occupation convinced me that he was saying something very important about why we need to be vigilant about xenophobia, the overreaching of the state, and the vulnerabilities of economic crises.

AWP: How did this extraordinary period become essential in forging the spirit of the European Union we know today?

TM: The European Union is a great achievement, and it is not the same thing as what Hitler imagined, needless to say. But Hitler did imagine a unified Europe under the Third Reich. From my perspective, that’s a very interesting fact.

WRITING

AWP: What inspired you toward a life and career so dependent on scholarship and the ability to communicate?

TM: My parents say that I announced my intention to become a writer when I was six, so I think telling stories might have always been part of how I made sense of the world.

AWP: Why did you feel that now, in particular, would be the right time to publish your book, The Hotel on Place Vendôme?

TM: The timing of this book and the closure and reopening of the Ritz during the renovations was a complete coincidence. The story grew naturally out of my research on Coco Chanel. It is an exciting time for books on the Second World War because so many new documents are being declassified each day at the moment. That was a definite factor.

AWP: When you started writing The Hotel on Place Vendôme, did you have a sense of what you wanted to do differently from other authors whose work you had seen?

TM: While I hoped this book would appeal to the hard-core history buffs, above all I wanted to write a story for people who also didn’t think of themselves as drawn particularly to the Second World War. So this is a very character driven history book—about the relationships among people and how the course of our lives can be shaped by the history going on around us.

AWP: Are there things that you feel haven’t been said about the occupation that you are trying to explore in your work now?

TM: My next book will be on the Polish Holocaust heroine Irena Sendler and on the group of “average” people who gathered around her to do courage things. For me, that’s the most interesting part of the Second World War: the stories we are still discovering of people with immense courage and dignity.

AWP: Your books, The Widow Clicquot and The Secret of Chanel No.5, have had a huge impact on Francophiles, historians and expatriates living in France. What do you think it is about your books that make readers connect in such a powerful way?

TM: What I hope readers take away from my books is both my love for France—a place I’ve spent many, many happy parts of my life—and a sense of a clear-eyed view of what has shaped that culture and especially the experience that so many expatriates have of it. One of the wonderful things about being an expatriate is the chance to love a country and to know it intimately but to see its strengths, flaws, and complexities with a certain kind of emotional disengagement. My husband is a Canadian, and so it’s something I’ve been thinking about especially in the last year or so all over again.

AWP: Could you talk about your process as a writer?

TM: I’m one of those writers who are very disciplined, largely because I find that gives me the most freedom. I write in the mornings, six days a week, and I give myself a number of words. When I’ve written 500 great words (or whatever the number is; it varies), it doesn’t matter what time it is. If it’s 10 AM, I can kick off for the day and treat myself to an afternoon of leisure. Other days, I’m chained to the computer still at 3 PM, and that’s just the reality of being a writer. After I finish a book, I do take a few months off from writing (but not reading or researching) just to recharge.

AWP: Some women and men are predisposed, each in their own way, toward a passion for France: through fantasy, family or cultural context. How did your interest in France unfold?

TM: I suppose my love affair with France began very early—certainly by the time I was a teenager. During high school, I worked summer jobs and saved up all my money, because I was determined to head for Paris the minute I was old enough. I was seventeen when I first decamped on my own for Europe, which of course caused my parents some consternation.

AWP: What French cultural nuances, attitudes, ideas, or habits have you adopted? In which areas have you embraced a similar aesthetic?

TM: My friends know that the French habits of chic scarves and beautiful perfumes came to me quite naturally and many years ago. I adore the July soldes and the ritual of proper mid-day lunches. The French sense of politesse is also one I admire, especially the way even young children are taught to be gracious. My aesthetic, though, remains very much West Coast and American. Our home is mid-century modern, and I’m a reasonably serious mid-century modern collector. My personal style sense is also definitely a mix of Manhattan and California more than anything. In fact, I’ve always been struck how the Franco-American affinity runs in both directions. The French are quite interested in that décontractée American sensibility, and I love being asked on the streets by chic Parisienne where I found something or another that I’ve picked up in TriBeCa or Santa Monica.

AWP: What do you think today’s historical writers bring to the travelers’ experience?

TM: History is well lets us feel like travelers instead of tourists.

AWP: What is it about writers and Paris?

TM: I’ve always had the sense that the architecture of Paris is one important factor. The apartments clustered around internal courtyards in many of the buildings and the rooftop rooms are the kind of spaces writers are always seeking.

AWP: What was the last book you read? Would you recommend it?

TM: I’m taking a winemaking course University of California at Davis, and I have been reading a textbook chapter on organic chemistry reactions in fermentation. It’s not exactly light reading. But it is fascinating.

AWP Your life is extraordinary. What’s next?

TM: I’m already at work on a new book, and this summer it will be back to Berlin and Paris!

BOOKS RECOMMENDED by Tilar J. Mazzeo

Out Stealing Horses by Per Petterson

Molecular Gastronomy by Herve This

The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt

Acknowledgement: Iona Davidson, student of French and Italian at the University of Oxford, England, and English editor for A Woman’s Paris.

SELECTED BOOKS BY TILAR J. MAZZEO

The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris (HarperCollins, 2014)

The Secret of Chanel No. 5: The Intimate History of the World’s Most Famous Perfume (HarperCollins, 2010)

The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and the Woman Who Ruled It (HarperCollins, 2009)

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post John Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt). Preeminent writer on Paris, John Baxter brilliantly brings to life one of the most dramatic and fascinating periods in the city’s history. Uncovering a thrilling chapter in Paris’ history, John Baxter’s revelatory new book, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city we love today. (Interview with John Baxter, 2014)

French Impressions: Barbara Will on Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the intellectual life during wartime France. From 1941 to 1943, Jewish American writer and avant-garde icon Gertrude Stein translated for an American audience thirty-two speeches in which Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of state for the collaborationist Vichy government, outlined the Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from the public sphere while calling for France to reconcile with its Nazi occupiers. In her book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, Barbara Will outlines the formative powers of this relationship, treating their interaction as a case study of intellectual life during wartime France.

French Impressions: W. Scott Haine on the origins of Simone de Beauvoir’s café life and the entry of France into WWII. “Café archives” seldom exist in any archive or museum, and library subject catalogs skim the surface. Scott Haine, who is part of a generation that is the first to explore systematically the social life of cafés and drinking establishments, takes us from the study of 18th century Parisian working class taverns to modern day cafés. A rich field because the café has for so long been so integral to French life.

French Impressions: Dr. Alan T. Marty on the dark history of the City of Light. Alan T. Marty, MD, armed with an historically-informed exploratory spirit, has often encountered Paris’ endless capacity to evoke a mood, to surprise with similar absent/present paradoxes, as detailed in his A Walking Guide to Occupied Paris: The Germans and Their Collaborators, a book-in-progress. His work has been acknowledged in Paris dans le Collaboration by Cecile Desprairies, Hal Vaughan’s book Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War; and referenced in Ronald Rosbottom’s When Paris Went Dark, and in an upcoming book about Occupied Paris by Tilar Mazzeo.

Joan DeJean’s “How Paris Became Paris” – Capital of the Univers (excerpt). How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City by acclaimed author Joan DeJean. Paris has been known for its grand boulevards, magnificent river views, and endless shopping for longer than one might think. While Baron Haussmann is usually credited as being the architect of the Paris we know today, with his major redevelopment of the city in the 19th century, Joan DeJean reveals that the Parisian model for urban space was in fact invented two centuries earlier. Joan is the author of nine books on French literature, history, and material culture, including most recently The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual and the Modern Home Began and The Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafés, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour.

French Impressions: Marilyn Yalom’s “How the French Invented Love” a tradition of courtly and romantic love that reaches back into the 12th century. Marilyn Yalom’s latest book, How the French Invented Love: Nine Hundred Years of Passion and Romance, shares condensed readings from French literary works—from the Middle Ages to the present—and the memories of her experiences in France. The French have always assumed that love is embedded in the flesh and that women are no less passionate than men.

French Impressions: Alice Kaplan – the Paris years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, on the process of transformation. Author and professor of French at Yale University, Ms. Kaplan discusses her new book, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, and the process of transformation. By entering into the lives of three important American women who studied in France, we learn how their year in France changed them and how they changed the world because of it. (French)

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2014 Tilar J. Mazzeo. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

Photography copyright ©2014 Sarah Rose. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

1 comments

Nancy said:

May 12, 2015 at 2:37 pm

Hey, hope it isn’t too late, but this little interview was interesting and provided some insight into the author’s intent.

Enjoy…

Janet