French Impressions: Andy Fry on Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, Django Reinhardt, and jazz today (part two)

14 Thursday Aug 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Cultures, Interviews

Tags

African American music in France, African American musicians in France, Andy Fry King's College London, Bessie Smith jazz, Casino de Paris, Cotton Club Harlem jazz, Django Reinhardt Paris jazz, Duke Ellington, Folies-Bergère Paris, France, Guthrie P Ramsey Jr The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius Jazz History and the Challenge of Bebop, jazz age France, Jazz Age Paris, Josephine Baker Paris, Louis Armstrong, Ma Rainey jazz, Oxford London, Paris, Paris Blues Diahann Caroll Sidney Poitier Martin Ritt, Paris Blues Sidney Poitier Paul Newman Diahann Carroll Joaane Woodward Martin Ritt, Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture 1920-1960 Andy Fry, Ronald Radano University of Wisconsin-Madison, Sidney Bechet Paris jazz, Sunset Cafe in Chicago Jazz, The University of Chicago Press, Travis Jackson University of Chicago, Universities of Lancaster Berkeley California, University of Berkeley, University of California San Diego, University of Pennsylvania

Share it

(Part one) Andy Fry joined King’s College London Music Department in 2007, having previously taught at the University of California, San Diego, and as a visiting professor at Berkeley. He completed his graduate studies at Oxford and has also studied at the Universities of Lancaster, California (Berkeley), and Pennsylvania. Andy’s principal research areas are Jazz (particularly pre-1950, race, gender, and historiography) and music in twentieth-century France.

(Part one) Andy Fry joined King’s College London Music Department in 2007, having previously taught at the University of California, San Diego, and as a visiting professor at Berkeley. He completed his graduate studies at Oxford and has also studied at the Universities of Lancaster, California (Berkeley), and Pennsylvania. Andy’s principal research areas are Jazz (particularly pre-1950, race, gender, and historiography) and music in twentieth-century France.

The Jazz Age. The phrase conjures images of Louis Armstrong holding court at the Sunset Cafe in Chicago, Duke Ellington dazzling crowds at the Cotton Club in Harlem, and stars like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey wailing the blues away. But the Jazz Age was every bit as much of a phenomenon in Paris, where the French public found their own heroes and heroines at the Folies-Bergère and Casino de Paris.

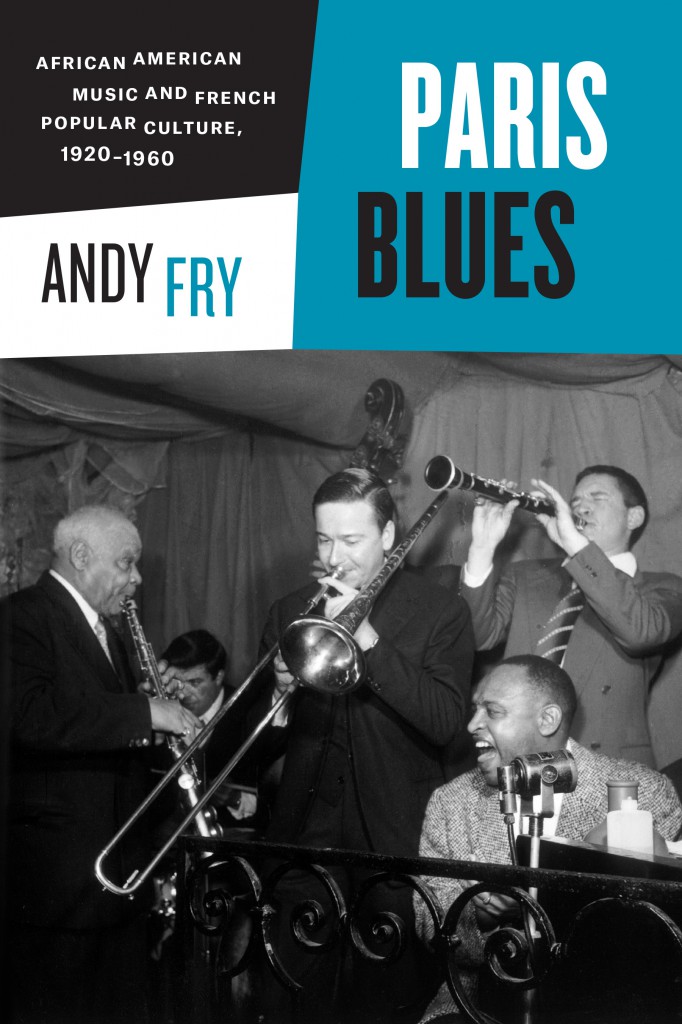

In Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, (July 15, 2014, The University of Chicago Press), Andy Fry provides an alternative history of African American music and musicians in France, one that looks beyond familiar personalities and well-rehearsed stories. While he deals with many of the traditional icons—such as Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and Sidney Bechet—he asks how they came to be so iconic, and what their stories hide as well as what they preserve. Paris Blues provides a nuanced account of the French reception of African Americans and their music and marks an important intervention in the growing literature on jazz, race, and nation in France. For more information about Andy Fry visit: (Website) (Purchase)

In Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, (July 15, 2014, The University of Chicago Press), Andy Fry provides an alternative history of African American music and musicians in France, one that looks beyond familiar personalities and well-rehearsed stories. While he deals with many of the traditional icons—such as Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and Sidney Bechet—he asks how they came to be so iconic, and what their stories hide as well as what they preserve. Paris Blues provides a nuanced account of the French reception of African Americans and their music and marks an important intervention in the growing literature on jazz, race, and nation in France. For more information about Andy Fry visit: (Website) (Purchase)

Excerpt from Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960. “Reprinted with permission from Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, by Andy Fry, published by the University of Chicago Press. (C) 2014 University Chicago Press. All rights reserved.”

“Fry has combined meticulous research with careful and creative use of sources from the worlds of music, film, history and popular culture more generally to produce an account that might, finally, bury the perennial (and perennially misguided) idea that Europeans and especially the French understood and appreciated jazz before Americans did. The story is false not only because African American and other U.S.-based supporters of jazz seem not to be ‘Americans’ in that version of history, but also because, as Fry eloquently argues, the French at times tried to claim jazz as their own creation, because ethnocentrism and paternalism were rarely absent from what they wrote, because the music and the musicians were often proxies in debates over national culture, and because musicians had reasons for living in France that previous scholars have failed to describe completely.” —Travis Jackson, University of Chicago

“What a pleasure to encounter this astute rethinking of the first forty years of jazz in France. Fry’s perceptive reading of the complex discourse network shaping the reception and practice of a broadly construed Parisian jazz is informed by an equally impressive command of a wide and deep historiography. The author’s engagingly written portrait not only upends some of the familiar narrations of Parisian jazz and its place in a wider jazz history; it also urges us to be a little smarter about how we talk and write about the place of jazz in the world today.” —Ronald Radano, University of Wisconsin-Madison

INTERVIEW: Paris Blues (Part Two)(Part One)

Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, and Django Reinhardt

AWP: You entrench your book in a different part of Josephine Baker (1906-1975, American-born dancer, singer, and actress), Sidney Bechet (1897-1959, American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, and composer), and Django Reinhardt’s (1910-1953, French guitarist and composer of Romani heritage) past, taking stock of their lives, as well as their work as performers for French audiences. What challenge did you encounter, and how did you unfold the story you wanted to tell?

AF: Writing about performers that are fairly well known, the problem is how to avoid telling the same story as has been heard dozens of times before: in these cases, specifically, Josephine Baker’s sudden stardom in La Revue nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in 1925, Sidney Bechet’s critical recognition by the celebrated Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet as early as 1919, and Django Reinhardt’s famous recordings with Stéphane Grappelli and the Quintet of the Hot Club of France in the mid 1930s. While I touch briefly on all these, to situate my chapters for readers new to their topics, I focus on far less commonly discussed events: Baker’s performance in a revival of Offenbach’s operetta La Créole in 1934; Bechet’s return to France in the late 1940s and subsequent decade of stardom; and Reinhardt’s remarkable success in occupied Paris during the Second World War. The hardest of these was the last one, since wartime sources are, for obvious reasons, far less plentiful and less well preserved than those from the periods either side. Still, many French newspapers and journals continued throughout the war, albeit with fewer pages. And secondary literature by specialist historians aided me to locate rarer sources. For me, it was fascinating to see how quickly people’s stories changed before, during, and after the war: this period marks an historical breach from which it was difficult for France, morally as well as practically, to recover.

AWP: Josephine Baker became a world-famous entertainer. Today do we celebrate her as an African American heroine, or a sign of successful French assimilation?

AF: This depends on exactly whom you ask, but her story does tend to look different whether you’re viewing it from the US or from France. Of course, African American music and culture is one of the US’s greatest exports and has been for a long time: people today rightly celebrate the pioneers; particularly given the obstacles they often had to overcome. France, on the other hand, has a reputation to uphold as an egalitarian country (an increasingly difficult task, given all the protests by minorities over recent years). Thus the French take great pride in their country’s adoption as home by foreign artists who achieved celebrity there. The problem, I think, is that neither of these positions takes into account the complex web of personal, professional, and social reasons that caused performers to make the choices that they did, or the exceptional nature of these stories. In other words, they may act as a smokescreen as much as an inspiration both for those still living lives of deprivation in the US, and for those majority from overseas who are denied legal residence in France.

AWP: An underlying theme in Paris Blues about Josephine Baker and Sidney Bechet is the message of freedom to experience their different selves or codify an articulate self in Paris. Why is this message significant, especially for musicians today?

AF: Both Josephine Baker and Sidney Bechet found that they had a popularity in Paris above all their expectations—Baker from the 1920s and Bechet in the 1950s (though he’d spent time there thirty years earlier). In both cases, I think, they struggled not to be subsumed by a French idea of what they were (or should be)—though they were prepared to go quite far in gratifying those expectations. In the process, Baker and Bechet became aware that identities are, to a large extent, “performed” by individuals rather than inherent to them—and thus can be shaped and reshaped over time. That’s to say that not just their relationship to their new home but their relationship to their old one, and indeed to their ethnicity, was open for continual negotiation. During the first decade of her career in France, after La Revue nègre in 1925, Baker went through a series of quick-fire image changes that progressively replaced a “primitive” African girl with a “sophisticated” Frenchwoman: both of them skilled performances that were taken as her true identity. After the war she matured into an even more versatile performer, able to put on and take off different versions of herself, while pursuing political goals of equality and respect that were brave and influential, if often impractical. Bechet, meanwhile, sought in his music and his autobiography, to locate himself as the very root of jazz history. He also developed a notion of musical authenticity that amounted to a truthful response to a time and place, not a narrow definition of what was proper for a given idiom. In both cases, they were able to combine sufficient commercial success with deeper personal objectives: surely an object lesson for any musician.

JAZZ TODAY

AWP: You are making some very interesting discoveries about African American jazz in Paris through research. Are you finding an underlying message that is especially significant for us today?

AF: I suppose one underlying message of my work—and it’s not a very happy one—is that musical acceptance is not synonymous with social acceptance. We may like to think that differences dissolve up there on the bandstand—and sometimes, temporarily, perhaps they do—but those fleeting moments do not add up to real social change, which takes much longer to achieve: music is at best a prelude to this and at worst acts to disguise a lack of progress. I don’t believe in utopias, musical or otherwise: which doesn’t mean I’m not hopeful and don’t recognize the huge improvements of the last fifty or so years, simply that musicians alone don’t change the world and we shouldn’t expect them to.

AWP: How did this extraordinary period become essential in forging the spirit of an international jazz culture we know today?

AF: The 1950s and the 1960s were the defining period, I think, because this was when the festivals were established and international travel came to be the expectation not the exception. Of course, this was also the period in which jazz lost the mainstream audience that it had fleetingly held in the swing era to rock’n’roll. So jazz musicians increasingly had to forge international careers in order to survive.

WRITING

AWP: Do you feel you’ve brought a scholar’s point of view to a territory that had, for the most part, been popular culture and media territory in the accounts of African American jazz in Paris and French culture?

AF: Stories about African Americans in Paris are certainly popular in the media, though they tend to concentrate rather obsessively on a few key figures (Josephine Baker, Miles Davis, etc.). But jazz in France has long been a scholarly topic, too, if only because musicologists sought to explain French composers’ interest in the music, in the late teens and twenties. What I hope I’ve done is to bring a similar level of attention to African American music itself, not just its appropriation in classical music. So, yes, a scholarly approach to popular culture.

AWP: When you started writing Paris Blues, did you have a sense of what you wanted to do differently from other authors whose work you had seen?

AF: This is a difficult question to answer since many of the books that surrounded me as I wrote were not published when I first began researching this topic, way back when I was still a graduate student. At that time, I knew I wanted to concentrate on African American music itself, not French composers, and I knew I wanted to take a historical approach, not lose my critical faculties in misplaced nostalgia. Since then, a number of books have come out—by critics and historians of various kinds, though interestingly none by a musicologist. We all have our different interests and methods, but we share the impulse to move beyond anecdotes to a more rigorous historical approach.

AWP: What do you think today’s writer-historians bring to the music listener’s experience?

AF: What I at least hope to bring is a sense of the music’s origins in a particular time and place, and the meaning it conveyed there and then. But music speaks differently to different people at different times. I’d never aim to contain music’s meanings. Rather, I believe that exploring music history can open up imaginative spaces for listening to sounds that might otherwise simply seem old and remote.

AWP: What things do you feel haven’t been said about African American music in Paris that you are trying to explore in your work now?

AF: One of the things I wasn’t able to explore in this book is the extent to which communities of musicians, critics, and listeners in different European cities were connected. African American musicians often visited Paris as one of a number of cities on a European tour, or used it as a base while forging a more broadly European career. Similarly, homegrown musicians in European cities often knew one another and played together, and critics shared information and published in each other’s journals. I’m seeking to explore these networks more now, with a particular attention to London, Paris, and various US cities in the 1950s.

AWP: What was the last book you read?

AF: Recently I’ve been in New Orleans, conducting research in the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University. My bedtime reading was two books by musicians “of a certain age”—one born in New Orleans and the other an émigré from London—who were just in time to learn from some of the founding fathers of jazz. They have fascinating stories to tell, both about the city and its musicians. The books are Tom Sancton, Song for My Fathers: A New Orleans Story in Black and White (New York: Other Press, 2006) and Barry Martyn, Walking with Legends: Barry Martyn’s New Orleans Jazz Odyssey (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007). Both musicians can still be heard playing live in New Orleans, too!

AWP: Your life is extraordinary. What’s next?

AF: I’ve been on sabbatical this year, completing the final stages of the publication process for Paris Blues and beginning work on this new project, on New Orleans jazz revival. So what’s immediately next is returning to teaching at King’s College London! Every chance I get, though, I’ll be back to my research—in New Orleans, Los Angeles, New York, Chicago and, sooner or later, Paris.

BOOKS AND VIDEOS RECOMMENDED BY Andy Fry

Martin Ritt, dir., Paris Blues. Los Angeles, Optimum Classic, 2008 [1961]. DVD.

Bertrand Tavernier, dir., ‘Round Midnight. Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2008 [1986]. DVD.

Jody Blake, Le Tumulte noir: Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900–1930. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

Bennetta Jules-Rosette, Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

Trica Danielle Keaton, T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, and Tyler Stovall, eds., Black France / France Noire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Ludovic Tournès, New Orleans sur Seine: Histoire du jazz en France. Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 1999.

Glenn Watkins, Pyramids at the Louvre: Music, Culture, and Collage from Stravinsky to the Postmodernists. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1994.

Acknowledgements: Alyssa Noel, student of French and Italian, and Journalism at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities and English editor for A Woman’s Paris.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post For Love or Money: Marriage and Divorce in the French capital (1880-1941) – Excerpt from Nancy L. Green’s “The Other Americans in Paris”. Nancy L. Green introduces us for the first time to the Right Bank American transplants. There were newely minted American countesses married to foreigners with impressive titles, American women married to American Businessmen, and many discharged American soldiers who had settled in France after World War I with their French wives. The book details the politics of citizenship, work, and business, and the wealth (and poverty) among the Americans who staked their claim to the City of Light.

Readers’ Choice: 146 Good Books for Summer About France (January to August 2014 resleases). Avid reader?Get a free reader’s list. If you subscribe, you’ll receive a free list as a welcome gift. Including: architecture, interiors and gardens, arts, biography, culture, fashion, food and wine, memoir, novel, science, travel, and war. Once subscribed, you’ll receive the free list—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber—and notifications of new posts by e-mail. You can unsubscribe at anytime. We never sell or share member information.

John Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt). Preeminent writer on Paris, John Baxter brilliantly brings to life one of the most dramatic and fascinating periods in the city’s history. Uncovering a thrilling chapter in Paris’ history, John Baxter’s revelatory new book, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city we love today. (A Woman’s Paris interview with John Baxter)

French Impressions: W. Scott Haine on the origins of Simone de Beauvoir’s café life and the entry of France into WWII.“Café archives” seldom exist in any archive or museum, and library subject catalogs skim the surface. Scott Haine, who is part of a generation that is the first to explore systematically the social life of cafés and drinking establishments, takes us from the study of 18th century Parisian working class taverns to modern day cafés. A rich field because the café has for so long been so integral to French life.

French Impressions: Barbara Will on Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the intellectual life during wartime France. From 1941 to 1943, Jewish American writer and avant-garde icon Gertrude Stein translated for an American audience thirty-two speeches in which Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of state for the collaborationist Vichy government, outlined the Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from the public sphere while calling for France to reconcile with its Nazi occupiers. In her book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, Barbara Will outlines the formative powers of this relationship, treating their interaction as a case study of intellectual life during wartime France.

McLain’s “Paris Wife” will have you head over heels for the Hemingways. Bethany Olson was drawn to McLain’s writing, detailed and thoughtful, that artfully captures Hadley’s voice and Ernest’s character in McLain’s fictionalized rendering of Hadley and Ernest’s relationship and their life in Paris. As did Hadley, Bethany found herself falling for for Ernest Hemingway, drawn to his exuberance, quick wit, and verve for life. Included are vimeos featuring interviews with Paula McLain by WHSmithDirect and BookLounge.

African-American Expatriates in Paris, by writer Kristin Wood who shares a few of our favorite books written by and/or about African-Americans in Paris and France. Some are novels; some are histories; all are fantastic reads.

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2014 University of Chicago Press. ©Andy Fry. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com