French Impressions: Andy Fry on the Jazz Age – African American music in Paris, 1920-1960 (part one)

12 Tuesday Aug 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Cultures, Interviews

Tags

African American music in France, African American musicians in France, Andy Fry King's College London, Bessie Smith jazz, Casino de Paris, Cotton Club Harlem jazz, Django Reinhardt Paris jazz, Duke Ellington, Folies-Bergère Paris, France, Guthrie P Ramsey Jr The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius Jazz History and the Challenge of Bebop, jazz age France, Jazz Age Paris, Josephine Baker Paris, Louis Armstrong, Ma Rainey jazz, Oxford London, Paris, Paris Blues Diahann Caroll Sidney Poitier Martin Ritt, Paris Blues Music, Paris Blues Sidney Poitier Paul Newman Diahann Carroll Joaane Woodward Martin Ritt, Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture 1920-1960 Andy Fry, Ronald Radano University of Wisconsin-Madison, Sidney Bechet Paris jazz, Sunset Cafe in Chicago Jazz, The University of Chicago Press, Universities of Lancaster Berkeley California, University of Berkeley, University of California San Diego, University of Pennsylvania

Share it

(Part two) Andy Fry joined King’s College London Music Department in 2007, having previously taught at the University of California, San Diego, and as a visiting professor at Berkeley. He completed his graduate studies at Oxford and has also studied at the Universities of Lancaster, California (Berkeley), and Pennsylvania. Andy’s principal research areas are Jazz (particularly pre-1950, race, gender, and historiography) and music in twentieth-century France. His articles and reviews have appeared in the Journal of the American Musicological Society, Cambridge Opera Journal, Music and Letters, and the Journal of the Royal Musical Association, as well as in Western Music and Race, ed. Julie Brown (Cambridge University Press, 2007), and The Oxford Handbook of the New Cultural History of Music, ed. Jane Fulcher (Oxford University Press, 2011). Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960 is his first book.

(Part two) Andy Fry joined King’s College London Music Department in 2007, having previously taught at the University of California, San Diego, and as a visiting professor at Berkeley. He completed his graduate studies at Oxford and has also studied at the Universities of Lancaster, California (Berkeley), and Pennsylvania. Andy’s principal research areas are Jazz (particularly pre-1950, race, gender, and historiography) and music in twentieth-century France. His articles and reviews have appeared in the Journal of the American Musicological Society, Cambridge Opera Journal, Music and Letters, and the Journal of the Royal Musical Association, as well as in Western Music and Race, ed. Julie Brown (Cambridge University Press, 2007), and The Oxford Handbook of the New Cultural History of Music, ed. Jane Fulcher (Oxford University Press, 2011). Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960 is his first book.

The Jazz Age. The phrase conjures images of Louis Armstrong holding court at the Sunset Cafe in Chicago, Duke Ellington dazzling crowds at the Cotton Club in Harlem, and stars like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey wailing the blues away. But the Jazz Age was every bit as much of a phenomenon in Paris, where the French public found their own heroes and heroines at the Folies-Bergère and Casino de Paris.

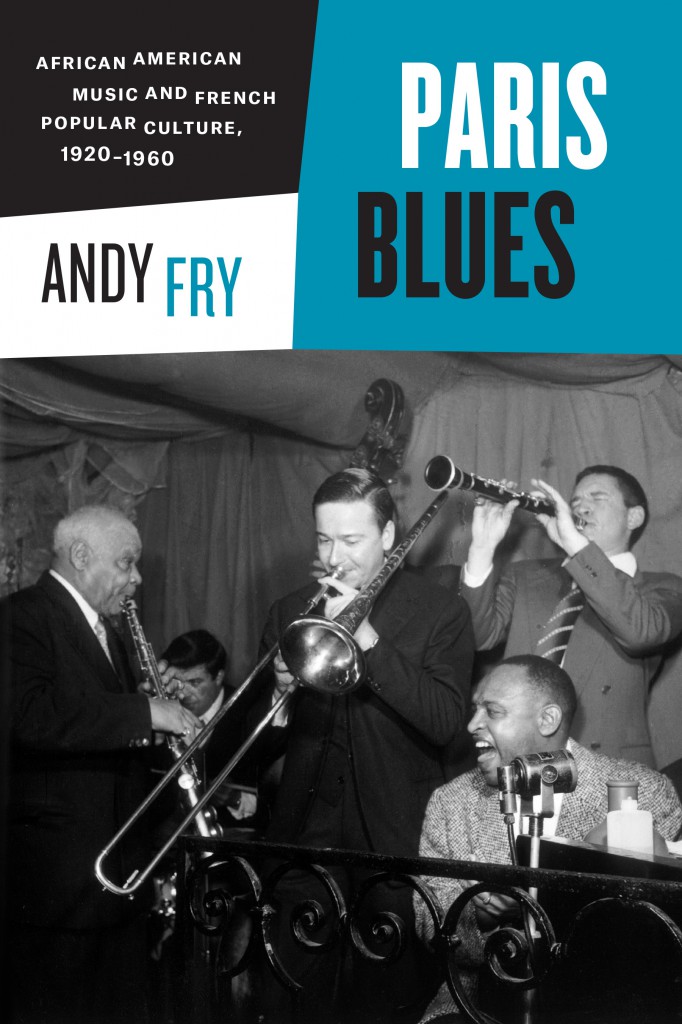

In Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, (July 15, 2014, The University of Chicago Press), Andy Fry provides an alternative history of African American music and musicians in France, one that looks beyond familiar personalities and well-rehearsed stories. He pinpoints key issues of race and nation in France’s complicated relationship with jazz from the 1920s through the 1950s. While he deals with many of the traditional icons—such as Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and Sidney Bechet—he asks how they came to be so iconic, and what their stories hide as well as what they preserve. Paris Blues provides a nuanced account of the French reception of African Americans and their music and marks an important intervention in the growing literature on jazz, race, and nation in France. For more information about Andy Fry visit: (Website) (Purchase)

In Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, (July 15, 2014, The University of Chicago Press), Andy Fry provides an alternative history of African American music and musicians in France, one that looks beyond familiar personalities and well-rehearsed stories. He pinpoints key issues of race and nation in France’s complicated relationship with jazz from the 1920s through the 1950s. While he deals with many of the traditional icons—such as Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and Sidney Bechet—he asks how they came to be so iconic, and what their stories hide as well as what they preserve. Paris Blues provides a nuanced account of the French reception of African Americans and their music and marks an important intervention in the growing literature on jazz, race, and nation in France. For more information about Andy Fry visit: (Website) (Purchase)

Excerpt from Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960. “Reprinted with permission from Paris Blues: African American Music and French Popular Culture, 1920-1960, by Andy Fry, published by the University of Chicago Press. (C) 2014 University Chicago Press. All rights reserved.”

“Paris Blues is a rich, thoughtful and diligently argued account of the African American muse’s great adventures in France during the twentieth century. Fry’s illuminating case studies—including from Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, Sidney Bechet, and more–revisit many of our preciously held views about modernism, black music, and French culture and teases out the complexities and pleasures that have made this intercontinental dance such a delight to revisit again and again.” —Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr., author of The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius, Jazz History, and the Challenge of Bebop

“Andy Fry’s ardently interdisciplinary set of historical analyses of the ongoing importance of African American music in the cultural life of France introduces innovative perspectives on Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt, and other major musical figures. This book incontrovertibly confirms the power of the new critical improvisation studies by affirming the centered place of music in any understanding of the human condition.” —George E. Lewis, author of A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music

INTERVIEW: Paris Blues (Part One) (Part Two)

AWP: You are the author of Paris Blues. What inspired you to write this book?

AF: I’ve always been interested in early twentieth-century French culture (the music, the literature, the art). A long time ago, when I was studying in California, I began taking classes also in African American music, which has since become my primary area of research. At a certain point, I realized that there was a way to put these two interests together—and the result is Paris Blues!

AWP: You entrench your work in a different part of Paris’ past, taking stock of the music scene and mapping the transformation of a new type of jazz. What challenges did you encounter, and how did you unfold the story you wanted to tell?

AF: The challenge is knowing when to stop. There are many stories to tell and extraordinary archives in Paris in which to research them—I could still be there, gathering new material every day. But the hard work comes when you get home and start to figure out not just what happened but what it all meant. For me, things often fall into place only in the process of writing. I organize my chapters around key events—like British bandleader Jack Hylton’s performance at the Paris Opéra, or Josephine Baker starring in Offenbach’s La Créole—but to discover their importance I need to go back a long way, to understand them in their own contexts.

AWP: During your research for Paris Blues, what aspect of African American music in Paris wouldn’t you include?

AF: I took a catholic approach, including both African Americans performing other types of music and Europeans playing jazz. Too often jazz scholars have employed very narrow definitions, based on the music they like (and think we should like) rather than what was actually popular at the time. To me, that misses the point of writing history—grappling with the foreignness of the past. Still, I had to make choices, the most important of which was to focus in the post-war period on the revival of New Orleans jazz rather than on the arrival of bebop. But this was a practical decision made to round out the book, not an aesthetic or ideological one—though I am crazy about Sidney Bechet!

AWP: Americans have a long tradition of viewing the French capital as a hospitable city for African Americans compared to the harsh realities of home. Did your research uncover a different reality? Does France ignore or downplay its own race problem?

AF: It’s hard to live in Paris and not notice that the people sweeping the elegant streets are not the same color as the people shopping on them. This is the same in many cities around the world, but in France discrimination is harder to gauge for the paradoxical reason that the law’s insistence on equality makes it difficult to ask about race. Thus racial inequality is visible on the street but invisible to the state, which cannot quantify it. African Americans have often (but far from always) said they were well treated in France. Yet we must not forget their point of comparison, at least until the 1960s: in large swathes of the States, segregation was still the law and fraternization between “races” could lead to arrest, violence, or worse; even the Northern states had a long way to go. So of course France was an improvement over the US, but it was no utopia. Paris Blues examines a number of the forms of racialism in which African American performance became engaged in its reception, from primitivist negrophilia through colonial policies to eugenics—all actively debated in Paris in my period.

JAZZ CULTURE IN PARIS (1920s – 1950s)

AWP: What was the network shaping the reception and practice of a broadly construed Parisian jazz?

AF: A lot of different groups were involved in the performance of African American music in France. For a start, African American musicians, of course! But they were not necessarily the most influential, or even the most numerous. There are many white Americans, too, and also some British bands such as that of Jack Hylton (who was called the “King of Jazz” in the 1920s). Some people would argue about whether all this music should still be called jazz, but I find it most helpful to follow the practice of the time. As specialist jazz critics emerged in the 1930s, there were protracted debates about what was and wasn’t jazz, and these discussions are an important part of the story. From a different perspective, the promoters of venues (from clubs to music hall to concert halls) as well as recording companies played an important role in determining which music was understood as jazz—and indeed how it should be understood, whether as popular entertainment or, increasingly, as art.

AWP: What was the popular imagination at the time? What were the social attitudes of the period?

AF: It depends exactly who and when we’re talking about, of course. But broadly speaking I trace a transition from the situation in the 1920s, when African American performers, such as Josephine Baker, were understood as primitive, erotic, and perhaps dangerous, to one, post-war, when Sidney Bechet could emerge as a kind of father figure to young musicians and youthful audiences: still “exotic” but in a charming, almost nostalgic way. This was partly down to his age, of course (Miles Davis was hardly treated the same way). But it was also because all forms of media, the movement of peoples, and of course the war itself, had given the French wider exposure to the world outside their borders. Throughout, what happened was that performers became bound up—in reception—with broader issues about France’s relationship to its empire and to the United States. In the 1920s, various “scientific” theories about racial mixing emerged in discussions about visiting troupes such as the Blackbirds, while polished big bands came to be seen as a sign of American “industrialization.” In the 1930s, Josephine Baker—who often played women from the French colonies and increasingly was understood as one—got caught in debates about immigrants’ capacities to assimilate. In other words, foreign performers acted as lightning rods for issues of much wider significance that swirled all around them. In this way, writing cultural history leads inevitably to social history more broadly conceived.

AWP: Did American jazz musicians in Paris add a Gallic tinge to jazz—swing local songs? Or play a type of jazz more accessible to Latin ears?

AF: Yes, both French and American musicians sought to encourage French identification with jazz by playing songs that were familiar. French bands of the late 1920s and 1930s made a big show of the fact that they were locals—which was more marketing than jingoism, I think. The long-lived band of Ray Ventura was among the first to do this, and for one of their medleys even located the regions of France from which each song came on a huge map. In the 1930s, the famous Quintet of the Hot Club of France established a more lasting model of French jazz—in terms less of the tunes that they played than their distinctive, all-string sound and perhaps the influence of Romani (“gypsy”) traditions. In the book, I write particularly about Sidney Bechet’s innovations of the post-war period, when he began adapting Creole songs from New Orleans (“Les oignons,” most famously) as well as composing some of his own in a simple, folky style (“Petite fleur”). These, along with his charming accent when speaking French, contributed to his nostalgic appeal, even though his music’s connection to France was largely invented.

AWP: What did African American music culture at that time imply for writers, artists, philosophers and political activists?

AF: African American music never meant just one thing, so the answer to this would again depend who you asked and when. In the 1920s, though, jazz was commonly aligned less with American culture than with African cultures—and often archaic African cultures at that. This is to say that it was regarded as a kind of “primitive” music, from a never-never land that was both historically and geographically distant, in the same way that African art objects such as masks were regarded by modernist painters like Picasso. The politics of such primitivism was complex in that it could signal radical anti-colonialism but it could equally well be limited to exoticizing escapism. Either way, the real cultures concerned had little say in their representation: their music and art became vehicles of the European imagination, even as movements for Pan-Africanism and African independence took off, and African Americans campaigned for recognition and rights in the States.

AWP: In interwar France, was French opinion on African Americans and their music straightforwardly political?

AF: I argue that it was not. There’s a pretty common idea—based mainly on composers’ appropriation of jazz—that African American music and musicians were received with great enthusiasm at the end of the First World War, but were gradually rejected as the political climate across Europe became more reactionary and nationalistic. I don’t really accept either part of that argument. African American musics were, from the start, intensely debated; opinion ranged from huge excitement to violent hostility but didn’t align closely to politics. Conversely, shortly before the Second World War, the greatest enthusiasm for black jazz was expressed by critic Hugues Panassié (a Royalist!) in the far right-wing press. So there’s not a clear connection, I don’t think, and certainly never anything like party positions on jazz in France.

AWP: How do we understand the grey-zone of jazz and the musician’s life in Paris during the occupation?

AF: You still often hear that jazz was banned in France during the war and went underground. A number of us have been doubting this story for a long time, but it’s now been comprehensively debunked by Gérard Régnier in his Jazz et Société Sous l’Occupation. Although African American musicians had, with rare exceptions, gone home before the war, French musicians continued to play jazz unabated; it was more popular during the occupation than ever it had been before the war. Of course, performing any kind of public function during the war meant frequent contact with the German occupiers. This wasn’t necessarily friendly or even willing contact—it wasn’t collaboration—but neither was it in most cases particularly antagonistic or resistant: it was just getting by. This is what I term, following another French historian, Philippe Burrin, “accommodation”: it represents, as he puts it, “the vast grey area that produces the dominant shade in any picture of those dark years” (Living with Defeat, trans. Janet Lloyd, p. 3). That’s the grey zone that most jazz musicians and listeners—like most people in general—occupied during the war, though of course there are exceptional cases on either side of it.

JAZZ CRITICISM IN FRANCE (1920s – 1950s)

AWP: What are the usual hallmarks that codified jazz “Hot”, “Straight”, and “Swing”?

AF: Jazz critics have expended a huge amount of energy over the years adjudicating what is and what isn’t “real jazz.” Looking back, a lot of this can be quite comical, since the arguments are often self-contradictory, or morph over time as the writers’ favorite artists break their supposed rules. In the 1930s, French critics such as Hugues Panassié sought to distinguish between “hot” jazz, which was rhythmically dynamic and featured improvisation, and “straight” jazz, which was played for dancing from written arrangements. But then Panassié tied himself in knots over Duke Ellington’s band, some of whose music was “straight” by the critic’s own definition—yet was unquestionably “authentic.” Panassié happened on the term “swing,” which was already in use among American players and critics to describe jazz musicians’ characteristic approach to rhythmic timing and interaction, and their attack and shaping of notes. This enabled him to explain how Duke Ellington’s band could sound so different from, say, Panassié’s bête noire Jack Hylton’s, even if they were playing the same arrangement without improvising.

AWP: What part did American journalists reporting in American magazines and newspapers published or represented in France provide to this community?

AF: There were a lot of American correspondents in Paris between the wars, including some for the African American press. They in particular were responsible for generating great pride among the black community at home about the achievements of performing artists abroad. Sometimes they also wondered whether it was correct to keep pandering to European tastes for comic stereotypes left over from minstrelsy, or primitive “jungle” roles. But more typically these reports were simple celebrations, describing the fame of the musicians and dancers and how well they were treated outside the United States. There were some white lies in those reports, ones that are too infrequently challenged today. But we must remember how powerful a motivator was the idea that black people were treated better elsewhere than at home—therefore that their lives in the United States could radically improve.

AWP: How is the story of jazz itself remembered and retold in French culture? What do they hide and what do they preserve?

AF: The whole story is often seen through rose-tinted glasses, I think. We remember the musicians who became successful and famous, not those—many more—whose careers didn’t take off, some of whom returned home deeply disillusioned. And we remember that some entertainers became popular, but not how they did so: the compromises they had to make to fit audience expectations of them and their music. This contrasts with the way stories about African American performers in the States are told, their achievements commonly seen against a background of social deprivation and industry exploitation. In Paris Blues, I try to bring a similar level of critical scrutiny to the situation in France. I celebrate the musicians’ achievements but I acknowledge that they, too, operated in a world that was far from perfect, facing critical and sometimes public hostility. To me, that makes their story all the more extraordinary. Harder to deal with is the fact that even those writers who were enthusiastic about the visitors often exoticized them to the point that they were not individuals but types, to be marveled over like a foreign species. Better to be a marvel than a horror, of course, but tragic if those are the only options.

AWP: How important was music criticism in France for crafting the story of jazz from the 1920s through the 1950s?

AF: I depend a lot—some would say too much—on music criticism to reveal what was on people’s minds at the time. There are some problems with this approach, of course: you only hear from professional writers (or those whose work includes some writing at least) who represent a fairly privileged subset of the population; they may have personal or even financial stakes in the success or failure of particular performers, too. I try to offset this as much as possible by consulting a very wide range of sources, from specialist music journals through daily newspapers to general-interest magazines, each with their particular readers in mind. I also try to “read through” writers’ commentaries to the responses of others: for example, critics commonly describe the reactions of other audience members, even if to disapprove. In Paris Blues, musicians’ own accounts feature fairly rarely, since my focus is on French reactions to African American music and musicians rather than on African American reactions to the French. There are exceptions to this, in that I write at some length, for example, about Sidney Bechet’s autobiography Treat It Gentle, which was written in the same period of his career as I discuss, the 1940s and 1950s. But for the most part, performers have written or spoken about their times in France long after the fact, and this makes their accounts a little unreliable as historical sources: can you recall in detail what you did, how you felt, or—still harder—how others felt about you thirty, forty, or fifty years ago? Besides which, these musicians’ narratives have been well mined for information by other writers: in Paris Blues, I wanted to locate their stories in a broader historical and social context.

Acknowledgements: Alyssa Noel, student of French and Italian, and Journalism at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities and English editor for A Woman’s Paris.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® blog, French Impressions: Alice Kaplan – the Paris years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, on the process of transformation. Author and professor of French at Yale University, Ms. Kaplan discusses her new book, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, and the process of transformation. By entering into the lives of three important American women who studied in France, we learn how their year in France changed them and how they changed the world because of it. (French)

Tilar J. Mazzeo’s “The Hotel on Place Vendôme” – Hôtel Ritz in Paris: June 1940 (excerpt). Tilar J. Mazzeo, author of the New York Times bestseller The Widow Clicquot, and The Secret of Chanel No. 5. This riveting account uncovers the remarkable experiences of those who lived in the hotel during the German occupation of Paris, revealing how what happened in the Ritz’s corridors, palatial suites, and basement kitchens shaped the fate of those who met there by chance or assignation, the future of France, and the course of history.

Joan DeJean’s “How Paris Became Paris” – Capital of the Universe (excerpt). How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City by acclaimed author Joan DeJean. Paris has been known for its grand boulevards, magnificent river views, and endless shopping for longer than one might think. While Baron Haussmann is usually credited as being the architect of the Paris we know today, with his major redevelopment of the city in the 19th century, Joan DeJean reveals that the Parisian model for urban space was in fact invented two centuries earlier.

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2014 University of Chicago Press. ©Andy Fry. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com