French Impressions: John Baxter on the First World War: A reflection on Paris’ history and transition during the war years

15 Tuesday Apr 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Cultures, Interviews

Tags

A Dance Between the Flames Anton Gill, A Pound of Paper John Baxter, An Honourable Defeat Anton Gill, Années Folles Paris, Art Déco Paris, Art Nouveau Paris, Belle Époque Paris, Chronicles of Old Paris, Chronicles of Old Paris John Baxter, City of Light, Constellation of Genius Kevin Jackson, Eiffel Tower, Ernest Hemingway, First World War Paris, French fashion, Gertrude Stein, Immoveable Feast John Baxter, Jazz Age Paris, Mayflower Kevin Jackson, Midnight in Paris, Pablo Picasso, Paris at the End of the World John Baxter, Paris fashion, Paris Writers Workshop, Salvador Dali, Surrealists, The Golden Moments of Paris John Baxter, The Great War, The Lost Generation Paris, The Most Beautiful Walk in the World John Baxter, The Paris Men's Salon John Baxter, The Perfect Meal John Baxter, We'll Always Have Paris John Baxter, World War I Paris

Share it

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is author of the memoirs The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, and Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918 (April 16, 2014). A native of Australia, he lives with his wife and daughter in Paris, in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is author of the memoirs The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, and Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918 (April 16, 2014). A native of Australia, he lives with his wife and daughter in Paris, in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

Since moving to France, John has published biographies of Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Josef von Sternberg, Robert De Niro and the author J.G. Ballard, as well as five books of autobiography, including A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. His most recent books are Chronicles of Old Paris and The Paris Men’s Salon, a selection from his uncollected prose pieces. John’s translations of Morphine, by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest and Fumée d’Opium, by Claude Farrère, have also been published by HarperCollins, the latter as My Lady Opium.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the Internet in search of new acquisitions.

In 1974 John was invited to become a visiting professor of film at Hollins College in Virginia, U.S.A. While in the U.S.A, he collaborated with Thomas Atkins on The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, a highly successful book of scientific speculation, and wrote a study of director King Vidor, as well as completing two novels, The Hermes Fall and Bidding. (Facebook) (Website) (Excerpt: Paris at the End of the World)

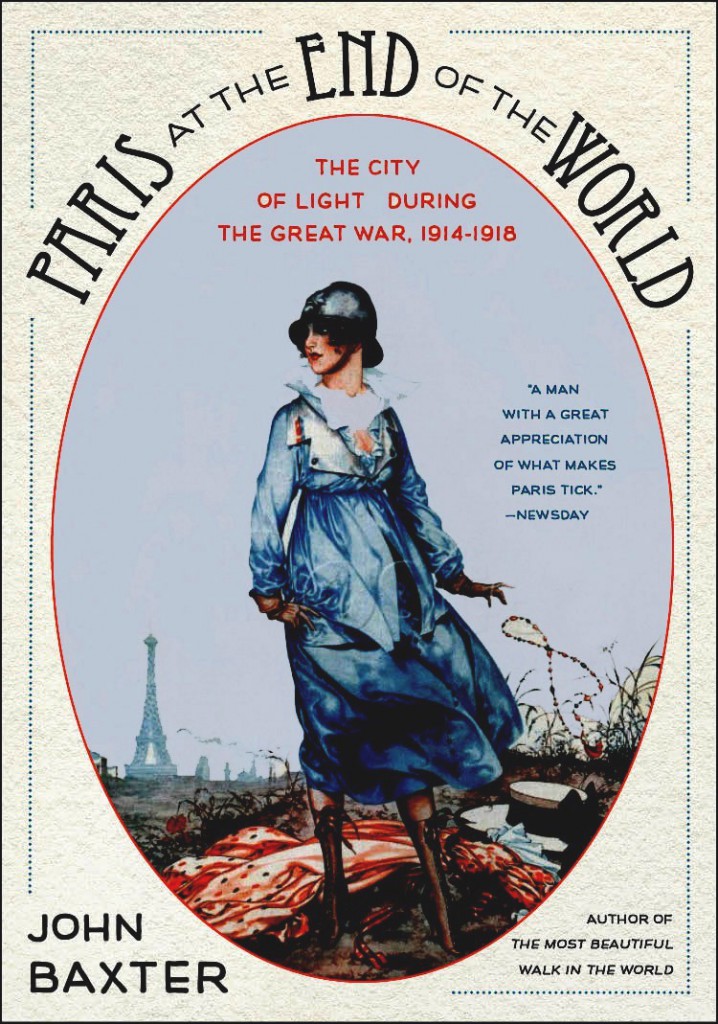

Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918

From 1914 through 1918 the terrifying sounds of World War I could be heard from inside the French capital. For four years, Paris lived under constant threat of destruction. And yet in its darkest hour, the City of Light blazed more brightly than ever. Its taxis shuttled troops to the front; its great railway stations received reinforcements from across the world; the grandest museums and cathedrals housed the wounded, and the Eiffel Tower hummed at all hours relaying messages to and from the front.

From 1914 through 1918 the terrifying sounds of World War I could be heard from inside the French capital. For four years, Paris lived under constant threat of destruction. And yet in its darkest hour, the City of Light blazed more brightly than ever. Its taxis shuttled troops to the front; its great railway stations received reinforcements from across the world; the grandest museums and cathedrals housed the wounded, and the Eiffel Tower hummed at all hours relaying messages to and from the front.

At night, Parisians lived with urgency and without inhibition. Artists like Pablo Picasso achieved new creative heights. And the war brought a wave of foreigners to the city for the first time, including Ernest Hemingway and Baxter’s own grandfather, Archie, whose diaries he used to reconstruct a soldier’s-eye view of the war years. A revelatory achievement, Paris at the End of the World shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city beloved today. (Excerpt: Paris at the End of the World)(Purchase)

“The most original and unexpectedly beguiling account of the Great War I have ever read. John Baxter is one of the master storytellers of our age, and by telling the tale of his half-forgotten grandfather, plucked out of sleepy Australia and pitched into the European massacre, he has been able to re-create not only the all-too-familiar Hell of the trenches but also the Heaven of sex and food and hedonism that was Paris at the twilight of its golden age. A revelation, an adventure, a joy to read.” —Kevin Jackson, author of Mayflower: The Voyage from Hell and Constellation of Genius: 1922: Modernism Year One

“John Baxter’s latest book marks the centenary of the beginning of the First World War with an intimate memoir of his grandfather’s experiences of that war, into which he weaves a reflection on its history, together with an examination of a Paris in transition during the war years – a transition which transformed the city of Art Nouveau and the Belle Époque into the city of the Jazz Age, invaded by Americans fleeing Prohibition, and the city of Art Déco. All this is done with Baxter’s inimitable lightness of touch and conversational style, which often belies the profound knowledge he has of his adoptive city.” —Anton Gill, author of A Dance Between the Flames: Berlin Between the Wars and An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler, 1933-1945

Excerpt: John Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt), published on A Woman’s Paris®.

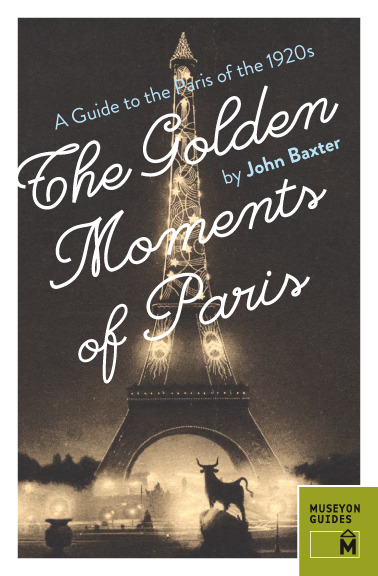

The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s

Following the popular Chronicles of Old Paris, in The Golden Moments of Paris, John Baxter has uncovered more fascinating true stories about the characters that gave Paris its character in the years between World War I and World War II. Explore more about one of the worlds most beautiful and loved cities in twenty-six fact-filled, humorous, and dramatic stories about the famed Années Folles -the Crazy Years at the turn of the 20th century in Paris. Learn about Gertrude Stein and her famous writers salon, Salvador Dali and the Surrealists, the birth of Chanel No. 5, and the antics of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the lost generation. Then see what these areas look like today by following along on the guided walking tours of Paris’s historic neighborhoods and the cafes, clubs, and brothels that were home to the intellectuals, artists, and Bohemians, illustrated with color photographs and period maps. If you enjoyed Woody Allen’s film Midnight in Paris, you’ll love this book. (Purchase)

Following the popular Chronicles of Old Paris, in The Golden Moments of Paris, John Baxter has uncovered more fascinating true stories about the characters that gave Paris its character in the years between World War I and World War II. Explore more about one of the worlds most beautiful and loved cities in twenty-six fact-filled, humorous, and dramatic stories about the famed Années Folles -the Crazy Years at the turn of the 20th century in Paris. Learn about Gertrude Stein and her famous writers salon, Salvador Dali and the Surrealists, the birth of Chanel No. 5, and the antics of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the lost generation. Then see what these areas look like today by following along on the guided walking tours of Paris’s historic neighborhoods and the cafes, clubs, and brothels that were home to the intellectuals, artists, and Bohemians, illustrated with color photographs and period maps. If you enjoyed Woody Allen’s film Midnight in Paris, you’ll love this book. (Purchase)

“…The city has had many golden ages but probably none as famous as the 1920s: the Paris of the Lost Generation. This is the Paris of Hemingway and the Fitzgerald’s’, of Gertrude Stein and so many others, when the City of Light was a veritable living museum of cultural activity: literature, music, art, dance…” —Chicago Tribune

INTERVIEW

Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918

AWP: You are the author of Paris at the End of the World. What inspired you to write this book?

JB: Australia, where I grew up, is particularly proud of it sunny climate, its sporting tradition and its military history. However sport never appealed to me, I much preferred shade to sun, and I was ambivalent about the military tradition.

My paternal grandfather William Archie Baxter, volunteered to fight in 1917, was shipped to France, and returned in 1919 in a highly dissatisfied state of mind. Initially he refused to go back to his wife, family or job. When he finally did, he spoke often about Paris, scattering French words and phrases through his conversation. As a boy, my father memorized these without completely understanding them. In time, I learned them too – again without fully appreciating what they meant.

What actually happened to Archie in Paris became a family mystery. I decided to solve it, using the little he’d left in the way of evidence; a few souvenirs, postcards, the records of his military service and the memories of other Australians who went through the same experiences.

Doing so lifted a corner of the curtain that obscured life in Paris during the four years of the war. I wondered how Parisians (not usually outgoing and accessible) coped with the influx of Australians, Americans, Canadians and Britons. The more I learned, the more fascinated I became with life in wartime Paris. During those four years, the gracious belle epoque came to an end, and les années folles – the crazy years – began. It was, literally, the end of a world.

PARIS AT THE END OF THE WORLD interweaves the story of those years with my account of how I solved the mystery of my grandfather’s time in France.

AWP: Paris at the End of the World, for the most part, is a revelatory work from your grandfather William Archie Baxter’s diaries of World War I. How did you uncover these diaries; oral or written histories from your grandfather or family members, or soldiers who served in the war alongside your grandfather?

JB: Australia zealously celebrates and documents its military history. Anzac Day, comparable to Veterans Day, is a major event, celebrated with marches and ceremonies of remembrance in even the smallest town. Its involvement in the Great War is regarded as the first collective achievement of the new country. The National Archives and the Australian War Memorial have accumulated enormous quantities of documentation. Once they had given me copies of Archie’s military history, I started filling in the gaps.

AWP: How did the diaries from your grandfather influence your book Paris at the End of the World?

JB: They were the reason for it, really. People like Archie had never travelled more than a few hundred miles in their lives, let alone gone abroad. They knew only one language and one way of life. Thrown into one of the most complex cultures in the world, they struggled to cope. Oral histories, letters and postcards give the specific details of how they adjusted, or failed to.

AWP: Your research is exemplary. How did you accumulate and obtain this information? From civil and court records, memoirs, letters, eyewitnesses, among others? Was the information primarily in French?

JB: Accounts of life in Paris between 1914 and 1918 are surprisingly skimpy. There are a number of reasons for this. News was strictly censored, and often distorted for the purposes of propaganda. Some reports of life at the front show it as a kind of holiday. I include an illustration showing troops playing with pets and cultivating gardens in the trenches.

Fortunately dozens of French magazines commented obliquely on the war through cartoons and caricatures. I collected hundreds of these magazines. They helped me reconstruct what was really going on in the lives of Parisians.

AWP: You are making some very interesting discoveries about Paris during World War I through research and the diaries of Archie Baxter. Are you finding an underlying message that is especially significant for us today?

JB: In writing the book, I often thought of John Milton’s line “they also serve who only stand and wait”. The endurance and fortitude of the both soldiers and civilians was remarkable. I’m not sure we still have the ability or willingness to dig in and tough out a national disaster of such proportions.

AWP: You entrench your book in a different part of Paris’ past, taking stock in the civilian, as well as the lives of those who fought at the front. What challenges did you encounter, and how did you unfold the story that you wanted to tell?

JB: Finding a point of view is often the most difficult task when starting a book. Instead of describing the period from a distance, as a detached observer, I made it a kind of memoir, narrating the process, so that the reader can follow me as I search for Archie’s secret and investigate the period. Hopefully people will become involved in the story, and share my curiosity about the outcome.

AWP: When you started writing Paris at the End of the World, did you have a sense of what you wanted to do differently from other authors whose work you had seen?

JB: I didn’t want to write another book about the horrors of the Great War. Those have been amply covered by other writers. What interested me was the way Parisians resisted that “hatred and despair.” Even with a war literally on their doorstep, they continued to create, and to find joy in life. Some disapproved of what looked like hedonism. “The worse the war is, the more depraved the civilians become,” novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline grumbled. “Women seem to have a fire in their ass. In time of war, instead of dancing in the lobby, we dance in the cellar.”

AWP: What did café culture during World War I imply for writers, artists, philosophers and political activists?

JB: Jean Cocteau, one of the main characters in PARIS AT THE END OF THE WORLD, said “there are two fronts in this war – the trenches and the Montparnasse front.” French artists and intellectuals were painfully aware of the war, but felt they could best contribute by keeping alive the values for which it was being fought. Cafes had become essential to the intellectual life of Paris. They were a place to work in warmth and comfort, to meet friends, to linger and talk. They functioned as artistic stock exchanges where ideas were swapped and projects planned. There genuinely was a “Montparnasse front.”

AWP: How descriptive were the writings of common life on the streets and in the cafés and the goings on around them by writers and philosophers, in particular?

JB: The great works of realist fiction about the war, such as Barbusse’s Le Feu, Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, were all written after the war. While hostilities continued, few writers felt able to stand back and take a properly dispassionate view. Most used poetry, satire or performance to express their concerns. I use the ballet Parade as an example. Cocteau conceived a ballet about travelling circus performers, enlisted Picasso to design it, and travelled with him to Rome to pitch the idea of Serge Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Eric Satie agreed to write the music, which scandalized the whole of Paris by including such dance rhythms as the jazz One Step, until then associated only with American minstrel shows. When critics attacked Parade as “unpatriotic”, Cocteau said “Laughter is natural to Frenchmen: it is important to keep this in mind and not be afraid to laugh, even at this most difficult time.” One unusual detail I discovered – couples were so stimulated by the music and the general air of transgression that it became fashionable to hire a box for a performance and make love while it was taking place.

AWP: During the early years of World War I, did many writers, philosophers and artists believe they were framers of a new era? Do we know their shared “truths”? Were they caught in their own web of self-proclaimed “genius” or did they see themselves as historical interpreters, thereby influencing events around them?

JB: The Great War was exceptional in that everyone expected it would be averted at the last minute. Even when it began, the generals confidently predicted it would be “over by Christmas.” Young men rushed to enlist; worried peace would come before they had their adventure.

Most writers saw war as a chance to reaffirm neglected values like heroism and nationhood. The British poet Rupert Brooke felt war “caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping/With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power/To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping.” To the American Malcolm Cowley, the imminence of death made every other sensation more vivid. “Danger was a relief from boredom; a stimulus to the emotions, a color mixed with all others to make them brighter.”

Like Cowley and Hemingway, Cocteau enlisted with an ambulance unit but saw the whole thing as a kind of joke – a vision that inspired his novel Thomas the Imposter. His poems depicted casualties with a poetic detachment. As the war dragged on, however, perspectives changed. The “self-proclaimed geniuses” sobered up quickly after the worst battles of 1915. Cocteau, one of the worst offenders, left the ambulance service to become a propagandist after, as he wrote, ” I realized I was enjoying myself.”

AWP: How did this extraordinary period become essential in forging the spirit of Paris we know today?

JB: I hadn’t understood quite how fundamentally art and literature were transformed by the war. When it ended, Britain, France and Germany were bankrupt. The cheap franc encouraged the rush of American tourists that created the expatriate culture of Paris between the wars and re-made literature. André Breton’s insights into the imagination, gained during his work in a psychiatric hospital caring for war casualties, led directly to Surrealism. Jazz, brought to France first by the African-American bandleader James Reese Europe to entertain the troops, transformed contemporary music… There are numerous such examples.

AWP: Is there one statement that channels everything you have uncovered about World War I?

JB: In 1914, H.G. Wells forecast that the forthcoming conflict, by destroying German militarism, would be “the war that will end all wars.” He could hardly have been more wrong.

WRITING

AWP: What do you think today’s historical writers bring to the travelers’ experience?

JB: Americans in particular have a romantic attachment to Paris, probably going back to the influx of soldiers during the Great War and the tourism that followed. Many would like to do what I did – visit Paris when they were old enough to enjoy and understand the city. Most never get beyond the wish, and those that do are generally limited to a couple of weeks in the city. For those who can’t stay longer or can’t come at all, my books provide an armchair visit to the city, with glimpses behind the doors that are usually closed to strangers. I’m pleased that I can share some of my delight with my adoptive home.

AWP: What is it about writers and Paris?

JB: It would take another book to answer this question comprehensively. It’s particularly difficult to explain why writers in English come to Paris; you would expect them to choose London, since it’s the language centre.

As far as I can tell, most expect Paris to inspire them. Only a small number take courses in writing or actually write anything while they are here. They believe something will happen in Paris which, returning home, they can describe. Some think a French lover is the answer. Others believe there is a kind of Paris magic that confers inspiration, as the citizens of Berlin believe there in Berlinerluft – a “Berlin air” that rises from below the city and confers genius. It seems ridiculous – yet it’s surprising how often the formula seems to work. Paris has inspired more than its share of authors. Maybe it’s a special ingredient they put into baguettes…

AWP: Why did you feel that now, in particular, would be the right time to publish your book, Paris at the End of the World?

JB: Obviously the centenary of the outbreak of war was a factor. Also our own daughter Louise is just graduating from college and it seemed a good time to explain this part of her heritage. And I felt that Archie also deserved to be put to rest. In a way, this book buries him in France, which I suspect is what he would have wished. In returning to Australia, he found only frustration. In a way, I’m living on his behalf the life he wished he could have led in Paris.

AWP: You moved to Paris in 1989. What was Paris like nearly twenty-five years ago? How is it different today?

JB: Environmentally the city is cleaner. There’s almost none of the dog dirt about which people used to complain. (It’s become too expensive to keep large dogs, and landlords dislike them.)

Many more people ride bikes, since the city provides them almost free via the Vel’Lib system.

Tourism is even more popular now, so people who interact with the public usually speak English.

The ban on smoking in public has cleaned up cafes, which now smell much better. On the debit side, however, most cafes are now, effectively, restaurants, since food offers more profit than coffee. Loitering dreamily for hours in a café over a café crème, once a cornerstone of the Paris experience is no longer an option.

In part because of this re-purposing of cafes, restaurants have deteriorated. More than 80% admit they rely on frozen, freeze-dried or packaged products.

Politically, Paris remains left wing in a country moving to the right. Manifs – political demonstrations and marches – seem to take place every day, blocking traffic and demonstrating Parisians’ disagreement with national policy, particularly on health care, pensions and same-sex marriage.

AWP: When you moved to Paris, how did you grapple with the cultural differences? Can you share the moment when you knew it had changed for you?

JB: Another topic worth a book. In fact, I already wrote it – We’ll Always Have Paris. Briefly, you don’t so much grapple with cultural differences as try not to be bulldozed by them. As to becoming French, I never will; I’ll always be an outsider, even though I married into a French family. I did discover, quite quickly, that, whereas, in England, most things can be explained in words, in France one relies on inference, implication, suggestion – what the French call nuance. Body language conveys 80% of sense, so a flip of the hand, the raising of an eyebrow, a moue of the lips can say much more than words. I suppose I began to understand the French when I learned the importance of the shrug. (Oddly, there is no French word for “shrug”: one just…well, shrugs.)

AWP: What is the best part about living in Paris?

JB: As France is known as The Woman of Europe, the best part of living in Paris relates to what Simone de Beauvoir said about women in The Second Sex – that men regard women not as separate yet equal, but rather as “other” – a person who is not them. I’ve lived in a number of cities around the world, but Paris is not like any of them. In Los Angeles or London or Prague or Rome, one can look around and wonder “Where am I?” but never in Paris. As a city, it is not just different but “other”.

AWP: Tell us something we don’t know about Paris-–its style, food, culture or travel.

JB: You must never order a café crème – café au lait – after mid-day. It’s exclusively a morning drink. To the French, it’s as if you requested cornflakes for lunch. And under no circumstances ever call it a cappuccino.

AWP: What was the last book you read? Would you recommend it?

JB: The Yearning by Kate Belle, an Australian writer with whom I’m appearing on a panel at the Sydney Writers Festival in May to discuss Sex and Literature. It’s accomplished and highly erotic – a kind of Australian Lolita, told from the nymphet’s point of view. I’d certainly recommend it, particular to women readers.

AWP Your life is extraordinary. What’s next?

JB: If you mean in writing terms, I’ve just delivered Five Nights in Paris, a companion to The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, but dealing with nocturnal perambulation. And of course I’ll continue to give my literary walks, which are proving as popular as ever.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED by John Baxter

JB: On my Kindle at the moment, I have Swann’s Way, the first volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Melville’s Moby Dick, Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, William Gibson’s Burning Chrome and Pattern Recognition, Robert Parker’s Looking for Rachel Wallace, the anthology British Poems of the Thirties… Hous plus about a hundred other titles.

Acknowledgement: Bailey Roberts, Linguistics student at Macalester College and English editor for A Woman’s Paris.

SELECTED BOOKS BY JOHN BAXTER

Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918. Harper Perennial, April 15, 2014

The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s. Museyon Inc., 2014

The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France. Harper Perennial, 2013

The Most Beautiful Walk in the World: A Pedestrian in Paris. Harper Perennial, 2011

Chronicles of Old Paris: Exploring the Historic City of Light. Museyon Guides, 2011

Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas. Harper Perennial, 2008

We’ll Always have Paris: Sex and Love in the City of Light. Harper Perennial, 2006

A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2005

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® postJohn Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt). Preeminent writer on Paris, John Baxter brilliantly brings to life one of the most dramatic and fascinating periods in the city’s history. Uncovering a thrilling chapter in Paris’ history, John Baxter’s revelatory new book, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city we love today.

French Impressions: W. Scott Haine on the origins of Simone de Beauvoir’s café life and the entry of France into WWII. “Café archives” seldom exist in any archive or museum, and library subject catalogs skim the surface. Scott Haine, who is part of a generation that is the first to explore systematically the social life of cafés and drinking establishments, takes us from the study of 18th century Parisian working class taverns to modern day cafés. A rich field because the café has for so long been so integral to French life.

French Impressions: Barbara Will on Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the intellectual life during wartime France. From 1941 to 1943, Jewish American writer and avant-garde icon Gertrude Stein translated for an American audience thirty-two speeches in which Marshal Philippe Pétain, head of state for the collaborationist Vichy government, outlined the Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from the public sphere while calling for France to reconcile with its Nazi occupiers. In her book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, Barbara Will outlines the formative powers of this relationship, treating their interaction as a case study of intellectual life during wartime France.

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2014 John Baxter. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com