French Impressions: Shari Leslie Segall on melting into French culture

25 Thursday Jul 2013

A Woman’s Paris™ in Interviews

Tags

1889 Paris World's Fair, 90+ Ways You Know You're Becoming French Shari Segall FUSAC, American Hospital in Paris, Americans in Paris by Brian N Morton, Annie Oakley, Arc de Triomphe, avenue de Marceau, avenue Hoche, Bastille Day, Bechet, Buffalo Bill, Calder, Cassatt, Champs-Élysées, Christo Jeanne-Claude, cross-cultural communications, Degas, Doubleday/Bertelsmann Book Club, École de guerre École Militaire, Eiffel Tower, Fitzgerald, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation by Joseph J Ellis, France, France...Really!!!: The French Uncorked!, French culture, French love, French marriage, French politics, French Revolution, French War College, FUSAC.FR, Gare d'Orsay, Gershwin, Golden Triangle Paris, Hemingway, International Herald Tribune, Isadora Duncan, James Joyce, Josephine Baker, L'Institut d'études politiques, La Chanson de Roland, La Quête du Graal, Mosaic Press, Musée d'Orsay, Omar Sharif, Our Lady by Dale Gershwin, Paris, Paris Metro, Paris Without End The True Story of Hemingway's First Wife by Gioia Diliberto, pont neuf, Professional Women's Committee of the American Chamber of Commerce in France, Rudolf Nureyev, Sciences Po Paris, Shari Leslie Segall, Stravinsky, The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language by Steven Pinker, The Word According to Garp John Irving, Van Gogh, Voltaire's Candide

Share it

Shari Leslie Segall is a native of Philadelphia whose father was a violist in the Philadelphia Orchestra. She lived on both U.S. coasts before traveling the world and settling in Paris, where she has lived since 1985. She is an author and speaker and teaches English and Cross-Cultural Communication at Sciences Po Paris (L’Institut d’études politiques) and the French War College (École de guerre) within the Ecole Militaire. A runner who has completed 25 marathons, Shari’s articles on running (“The inner marathon, mile by mile,” April 2006; “The burden of being a champ,” March, 2008; “I must keep running,” April 2009), have appeared in the International Herald Tribune. Calling upon her insights into what makes our French cousins who they are, she shares her views in good humor about the inhabitants of her adopted country in her regular “Hints for Newcomers – Hindsight for Old-timers” column in FUSAC (France-USA Contacts), as well as in other publications. She is active in the American community in Paris and the founding chair of the Professional Women’s Committee of the American Chamber of Commerce in France. Prior to launching Foreign Affairs, a communication and training firm whose specialties include cross-cultural and language training as well as answering all the written and spoken English-language needs of French corporate and private clients, she worked as communication director for several entities, starting with the American Hospital of Paris.

Shari Leslie Segall is a native of Philadelphia whose father was a violist in the Philadelphia Orchestra. She lived on both U.S. coasts before traveling the world and settling in Paris, where she has lived since 1985. She is an author and speaker and teaches English and Cross-Cultural Communication at Sciences Po Paris (L’Institut d’études politiques) and the French War College (École de guerre) within the Ecole Militaire. A runner who has completed 25 marathons, Shari’s articles on running (“The inner marathon, mile by mile,” April 2006; “The burden of being a champ,” March, 2008; “I must keep running,” April 2009), have appeared in the International Herald Tribune. Calling upon her insights into what makes our French cousins who they are, she shares her views in good humor about the inhabitants of her adopted country in her regular “Hints for Newcomers – Hindsight for Old-timers” column in FUSAC (France-USA Contacts), as well as in other publications. She is active in the American community in Paris and the founding chair of the Professional Women’s Committee of the American Chamber of Commerce in France. Prior to launching Foreign Affairs, a communication and training firm whose specialties include cross-cultural and language training as well as answering all the written and spoken English-language needs of French corporate and private clients, she worked as communication director for several entities, starting with the American Hospital of Paris.

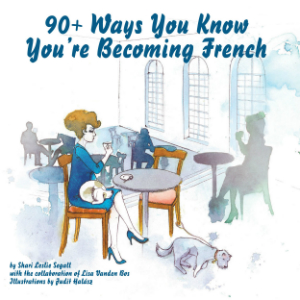

Her latest book, with the collaboration of Lisa Vanden Bos, 90+ Ways You Know You’re Becoming French, offers cross-cultural insights and lighthearted humor while gently holding a mirror up to France-based Anglos and their Gallic hosts. The book is published by Editions FUSAC and contains beautiful, engaging illustrations by Hungarian artist and designer Judit Halasz. Visit: (Purchase)

Her latest book, with the collaboration of Lisa Vanden Bos, 90+ Ways You Know You’re Becoming French, offers cross-cultural insights and lighthearted humor while gently holding a mirror up to France-based Anglos and their Gallic hosts. The book is published by Editions FUSAC and contains beautiful, engaging illustrations by Hungarian artist and designer Judit Halasz. Visit: (Purchase)

Shari’s first book, Our Lady, published in 1999 by Mosaic Press under her nom de plume, Dale Gershwin, was featured by the Doubleday/Bertelsmann Book Club. It was hailed as “Multi-media on the printed page” by www.paris-anglo.com. Her second book, France…Really!!!: The French Uncorked!, published by Mosaic Press in 2003 under her nom de plume, is a very short exploration of particular details of French culture: love and marriage, sports, religion, politics, etc. For more information on Shari Leslie Segall, visit: (Website, scroll down: http://www.i-ts.eu/fr/shari.html)

INTERVIEW

AWP: You write about the French and what makes them who they are. Do you have to do a lot of research? Or do you already know all this inside and out?

SLS: Getting up in the morning is all the research you need. To expand upon what I said in the FUSAC piece, Oh, so French! Crossing over to the other side, republished in A Woman’s Paris earlier this week, if you’re here long enough–and usually, this happens not very long after you arrive–your understanding of your adopted culture, and your adaptation to it, mirrors those Escher drawings where columns of black geese or fish on the left fly or swim straight across the page, migrating and mutating by imperceptible degrees, melting into and finally becoming their white counterparts on the right. To a greater or lesser degree, whether you expected to or not, one day you realize that you’re crossing to the other side–you “get” what the French are all about.

AWP: Your career has taken you from public relations into the world of teaching and writing books. What inspired you toward a life and career so dependent on words and the ability to communicate?

SLS: I think that’s like asking, “What inspired you to have blue eyes?” With all due respect to writers’ workshops and presentation seminars and the like, I think you’re either born a communicator or you’re not. You orally wow your mother from the crib or you don’t. I don’t think someone can be “taught” or “trained” to write brilliantly or give dazzling speeches or tell mesmerizing stories at a cocktail party.

AWP: You were a communications specialist working for the prestigious American Hospital of Paris and other entities. When you started writing books, what was the most difficult thing for you to learn?

SLS: Not to tell anyone you’re writing the book until it’s at least finished and at best published. Otherwise, you get comments like, “Oh, yeah. Sure. Everyone thinks they can write! Y’know, my cousin worked on a book for fifteen years. No literary agent would touch it. Good luck, sister!”

AWP: The American Hospital of Paris is often referred to as “where the rich and famous are treated.” What was it like working there?

SLS: For the six years that I worked there, I said to myself, “I can’t believe they’re paying me to have so much fun and so many exhilarating experiences!” It would take a library full of books to describe it all, but here are merely two examples: Omar Sharif is hospitalized. I need to go to his room to find out what I should tell the press if they ask about him. Lying there in all his beauty, he taps the side of the bed next to him and says, “Sit down, dear.” I sit on his bed, right up beside him. He takes my hand, and I ask him my question.

In 1986, the transformation of the Gare d’Orsay (Orsay Train Station) into the Musée d’Orsay (Orsay Museum) was completed. The American Hospital of Paris’s January 1986 fundraising gala was the museum’s first event. It took place at night. The museum was closed. Although I was “working,” I had to dress like everyone else in attendance. At one point, I wandered off by myself, away from the festivities, and entered a dark room. When my eyes adjusted to the dim light, I realized that there I was, alone, in my long black ball gown, surrounded in the stone-still silence by a roomful of Degas.

AWP: Could you talk about your process as a writer?

SLS: It’s as if what I want to write is already in the computer and all I have to do is tap on the keys for it to come out. I’m definitely a lark, not an owl, so when I write major works (I’ve also ghostwritten a book for the head of a French multinational, I co-wrote The American Revolution in Paris: In the Founding Fathers’ Footsteps and I’m shopping another novel around to literary agents), I work on them in the morning.

AWP: What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever been given?

SLS: It’s writing advice I read: I think it was John Irving (The World According to Garp, etc.) who said that the entire novel should be contained in the first sentence.

THE ART OF LIVING

AWP: You arrived in Paris in 1985–in context, the same year Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped the Pont-Neuf, the oldest bridge in Paris. What was Paris like, nearly 30 years ago? How is it different today?

SLS: It was more the same back then than different back then–which, in some (not all) aspects, is great. Otherwise, Paris would not be Paris. There of course have been many changes, three of which are as follows: Today’s no-smoking-in-public-places law did not exist. People smoked everywhere. On métro platforms. In métro cars. Needless to say, where food and drink were served. In offices. My great office-smoking story is that on my very first day in a post-American Hospital job, I arrived at my desk in a shared space. My officemate had no idea that a new person had even been hired, let alone that that person was going to share his office. I was a total stranger to him–a squatter, as far as he was concerned. I had not been there for more than a half hour when he started lighting a cigarette. “We don’t smoke in this office,” I said to him. You can imagine his reaction!

Whereas now, some bakeries outdo each other in the degree of exoticism to which their sandwich-making arts can take them, there were no sandwiches for sale in bakeries when I arrived. Everyone–everyone–either went out for an elaborate multi-course lunch; went to the company cafeteria for an elaborate multi-course lunch; or brought their own elaborate multi-course lunch, heated it in the company microwave and then took it to the company cafeteria. (Eating at your desk at the time was as inappropriate as hauling a photocopy machine into a restaurant and collating the annual report during the soup course would have been.) The only people who ate sandwiches for lunch were tourists, and those sandwiches had to be made from bread purchased in a bakery and contents purchased in a grocery store or supermarket. (But even today, the only people eating–sandwiches or anything–while walking on the street or riding on a public-transportation vehicle are tourists. Entering a métro car as you’re chowing down subjects you to brutal gawking. How many eyes does this métro car contain? That’s how many are trained on you in vicious condemnation.)

Yes, French women do now get fat. Thank you, McDonald’s!

AWP: Some women and men are predisposed, each in their own way, toward France: through fantasy, family or a cultural context. How did your interest in France unfold?

SLS: I was destined to live in Paris. Listing all the reasons I say this would take up too much of this interview, but here are several: By the end of my very first day in my very first French class, in junior high school, I felt as if I had been speaking the language all my life. Then, the teacher would say to the class, for instance, “Go home and study the chapter on the [extremely challenging] subjunctive. We’ll discuss it tomorrow.” By the next day I had totally mastered the subjunctive–or whatever language category du jour– and was painfully bored in class. When I moved to Paris, I predicted the street on which I’d find an apartment. That was the street on which I found an apartment. When I moved to Paris, I predicted the date by which I’d find a job. That was the date by which I found a job (the above mentioned American Hospital job, the best job in the world). I networked my way into that job in a matter of weeks, deflecting statements like “I hope you have enough money for plane fare back, because it’s extremely difficult for an American to find work here” and “I hope you can clean houses. You might find something in that field.”

AWP: What is it about Paris and writers?

SLS: You could ask, “What is it about Paris and artists (Calder, Cassatt, Van Gogh, etc.)?” “What is it about Paris and musicians (Gershwin, Beckett, Stravinsky)?” “What is it about Paris and dancers (Isadora Duncan, Josephine Baker, Rudolf Nureyev)?” Even “What is it about Paris and performing cowpeople (Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley were featured at the 1889 Paris World’s Fair, which commemorated the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution)?” For the between-the-two-World-Wars writers (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, etc.), it was the escape from Prohibition, the favorable franc-dollar exchange rate and the fact that in France, if at a cocktail party you said you were a poet or writer, you were lauded, not told to get a real job. The latter is still the case, as it is with all “intellectual” pursuits. Beyond that, will anyone ever be able to pinpoint and define why Paris is such a magnet to the creative, the bohemian, the true-to-their-soul?

AWP: When you moved to Paris, how did you grapple with the cultural differences? Can you share the moment you knew it had changed?

SLS: I’m still confronted with cultural differences. I am still gob-smacked by them. The gobsmackedness was, of course, more intense when I first arrived. I came with fluent French and a deep knowledge of French literature (including the ability to read La Chanson de Roland and La Quête du Graal in Old French), but my Philadelphia teachers obviously either had had no knowledge about French-U.S. cultural differences or had seen no need to impart information about them. Everyone looked like me, I reasoned, so why don’t they act like me?! My most illustrative cultural-difference story is: As communication director at the American Hospital I had to take pictures for various reasons. One of my peers had borrowed my camera and one day I popped by his office to get it back. I stuck my head in the door and asked (in French, of course), “Y’got the camera?” I had just arrived. I had been in that job for merely weeks. And for the next six months, no one but my (British) assistant spoke to me. After half a year of cold shoulders, I asked my assistant why she thought this might be. She told me that she had heard through the grapevine that when I first arrived I did something so rude that word got around that that was the kind of treatment I deserved back. She had not been told what it was, and neither she nor I had any idea of what I possibly could have done. So she went on an investigation mission and came back with the answer. It was the camera question. What I had not said that day, but should have, was: “Hi, Jean-Paul. Sorry to disturb you. How are you? How’s your family? Any plans for the end-of-year holiday? Listen: I am permitting myself to ask you if you would please be so kind as to return my camera.” Can you imagine how the time it took to say that in a U.S. company every time you wanted something from someone would be looked upon?

AWP: What French cultural nuances, attitudes, ideas or habits have you adopted? In which areas have you embraced a similar aesthetic?

SLS: I’m hugely non-French: I don’t drink, I have been a vegetarian for 43 years (a restaurant once refused to serve me, saying I was “insulting the chef” by not eating his meat specialties!), I go to bed breathtakingly early, I don’t like going out. But I have “become” French in one area: The French consider most any questions about their personal lives to be “indiscreet.” Even a question as seemingly innocent as “Where did you meet your wife?” sends shock waves up their cultural spines. What an American thinks is healthy, amicable, sincere interest the French consider dangerous, insidious, invasive in-butting. Don’t get personal with a newfound American friend and they’re insulted–they think you don’t care; get personal with a newfound French friend and they’re affronted–they think you care too much. For some reason, this is the French trait that has stuck to the walls of my American carapace.

AWP: Parisiennes dress well all of the time. How do you describe their understated elegance?

SLS: In a continuation of my answer about what has changed: Take out your Paris map. Find the Arc de Triomphe. Hold the page so that this is the vertex then look at the triangle of location! location! location! formed by the avenue Hoche as the right-hand leg, the avenue de Marceau as the left-hand leg and, roughly, the avenue Franklin Roosevelt as the base (the true site of the base is ever elusive and in dispute, especially among real estate agents for obvious reasons). This area is called the Golden Triangle. It is the Park Avenue of Paris, the Rodeo Drive of France, the high-rent, high-prestige district host to the legendary Champs-Elysées (literally–and classically–”the Elysian Fields”); the $10 cup of coffee; the venerable apartments wherein the master of the manor still picks up a little silver bell next to his dinner plate in order to ring for the servant who clears the dishes; and the only women in Paris, let alone France, who look understatedly elegant all the time. In the other 211,207 (out of 211,208) square miles of the realm, everyone looks more or less like you and me–at least some of the time.

AWP: What is the most valuable thing the Frenchwoman has to work with?

SLS: Her ability to look the other way when she knows her husband is cheating on her. She gets on with her (continuing-to-be-married-to-the-same-man) life. I am not happy about this or approving of it but given that infidelity is institutionalized here, at least the woman does not wind up in a state of function–impeding emotional paralysis. American men cheat too. But in the U.S. cheating is not considered part of existence on the planet. It’s considered hurtful and thus shameful. There are historical reasons for all this (as there are for most cultural phenomena), but they’d be way too long to go into in this interview.

AWP: How has the idea of the Parisienne changed since you began writing?

SLS: Not that this affects my writing (except for reporting about and/or commenting on it) but, as mentioned above, I am dumbstruck by the increase in the waistline of la parisienne since I got here.

AWP: What modern trend do you love the most?

SLS: In the category of urban trends, the fact that more street space is being set aside for biking, running, etc. Not enough, but at least there’s been increased sensitivity about this throughout the years.

AWP: We all feel less spending power from the recent downturn in the world economy. What do French women do differently? What do you do differently? What wouldn’t you give up?

SLS: I think the French are going on fewer expensive vacations. They still go on vacation–they’re the world champions in the art of time off-but I think they’re sticking closer to home. That might be one of the reasons that there seemed to be more people watching the Bastille Day fireworks under the Eiffel Tower this year, i.e., instead of going to Peru, the family came to Paris. I don’t do much differently because I never spent a lot of money. I don’t like a lot of “things.” I eat for extremely little money. I don’t like to go out. I don’t like to leave Paris. I hate waste and champion recycling (i.e., using a beautiful old mug as a cutlery holder, for instance, instead of buying a new cutlery holder–or whatever). My rent is astronomical, as are many rents in Paris, but other than that, I usually keep my spending down to a low roar. I wouldn’t give up running, but that doesn’t cost me anything (except for [universally expensive] shoes).

AWP: What is the last book you read? Would you recommend it?

SLS: Paris Without End: The True Story of Hemingway’s First Wife, by Gioia Diliberto. Wouldn’t recommend it. Well researched, well written, but got boring after a while. That might be due to my attention span; someone else, needless to say, might not be able to put it down.

AWP: Describe your own “Paris.”

SLS: As counterproductive (and pretentious) as this might seem–i.e., this is basically the point of this whole interview–I really can’t bring myself to do so, as Paris is so sacred to me. It’s kind of like Jews’ not being able to say the name of God. That said, after having read Our Lady one has a sense of my Paris.

AWP: Tell us something we don’t know about Paris–its style, food, culture or travel.

SLS: Here are corrections to some foreign-held misconceptions: The Sorbonne is not the best institution of higher education in France. It’s one of the world’s oldest universities. It’s an extremely good university. But in France, the equivalents of Ivy League schools are called grandes écoles (which the French erroneously translate as “big schools” on their CVs, leading recruiters to state that they do not care how many square feet the applicants’ schools occupied). Universités, as high performing as they may be, are second-class citizens in the hierarchy of types of higher-education establishments. No, the last guillotining was not during the 18th-century Reign of Terror. It was in 1977. No, Dr. Guillotin did not invent the guillotine. As a physician, he promoted it, as a more “humane” way to execute, stating that all that one feels is “a slight breeze on the back of the neck.” (How did he know this?) Tobias Schmidt, a German engineer and harpsichord maker (worked with wood–get it?) made the first guillotine. French women did not get the right to vote until 1944, did not gain the right to work or open a bank account without their husbands’ consent until 1965 and become the legal owners of their possessions in only 1966. And in 1789, when the Bastille was taken by the revolutionaries, there were only seven prisoners in it!

AWP: Your passion for life is extraordinary. What’s next?

SLS: To paraphrase Voltaire’s Candide at the end of the eponymous book, “I must cultivate my garden.”

BOOKS RECOMMENDATION BY SHARI LESLIE SEGALL

Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation, by Joseph J. Ellis (2000)

The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language, by Steven Pinker (1994)

Americans in Paris, by Brian N. Morton (1984)

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post, Oh, so French! Crossing to the other side. Paris-based writer Shari Leslie Segall shares her observations of becoming a little bit French after living in Paris for nearly thirty years and writes: “To a greater or lesser degree, whether you expected to or not, one day you realize that you’re crossing to the other side.” She offers a very incomplete list of how you know when you’ve arrived. (First published in FUSAC.FR July 5, 2013.)

Beauty Confessions from a Globe-trotting Parisienne. Parisienne Bénédicte Mahé shares a French woman’s approach to beauty and makeup; and how the relationship Americans have with beauty is very different from that of the French. Including her list of Beauty Resources in Paris and a vocabulary of French to English translations. (French)

What’s in a Word? There’s more to French class than you thought. Jacqueline Bucar, French teacher and immigration attorney, invites us to stimulate a way of thinking and learning that expands our understanding of the world and ourselves through the study of a foreign language. She shares “what’s in a word,” a way of thinking, a “mentality” that helps define the people who speak it and their culture. (French)

Ballet Flats in Paris: And God made Repetto, by Barbara Redmond who shares what she got from a pair of flats purchased in a ballet store in Paris; a feline, natural style from the toes up, a simple pair of shoes that transformed her whole look. Including the vimeos “Pas de Deux Coda,” by Opening Ceremony and “Repetto,” by Repetto, Paris. (French)

I dream of Paris. Writer and educator Natalie Ehalt shares the quote from Napoléon, who wrote in 1795, “A woman, in order to know what is due her and what her power is, must live in Paris for six months.” To Natalie, Paris is the ultimate in elegance and style. It is old-fashioned, it is cobblestone, it is aprons, it is a chauffeur helping you step off the curb…

A Woman’s Paris–Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2013 Shari Leslie Segall. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

5 comments

Martin Seldman said:

May 19, 2020 at 10:07 pm

Hi Shari,

I’ve been listening to some of your interviews and reading your articles. Nice to remember about St. Malo and first place we stayed in Paris.

Didn’t hear about Essaouira experience but maybe that wasn’t too high on your list.

Really enjoyed listening to you and sounds like you have had a rich wonderful experience following your heart.

Sorry I missed your 70th birthday recently but hope you had a good celebration, All the best Marty

Gee Hamilton said:

February 4, 2015 at 4:48 am

Is there any chance that your book will be available in England?

Brian Chatham said:

January 8, 2015 at 3:37 pm

Shari, Great to see you are still writing and doing well. I had the pleasure of meeting you on a brief stop in Paris. Your kindness and spirit made my short stay all the better. You obviously made an impression on me, since I still remember my visit after all these years. Take care and keep living!

Ellyn Glassman Bloomfield said:

August 14, 2014 at 1:08 am

Shari,

I believe that we went to Northeast High School together. I’m an old friend of Sue Black, Sheryl Geller and Sandy Krantz. I don’t know if you remember any of us from that time.

I thought this article was fascinating and enjoyed reading about your life in Paris. I’ve visited Paris many times and will be there in Sept. Best wishes.

Ellyn

Rick Cohen said:

September 25, 2013 at 5:07 pm

I read an article ‘Walking in Jefferson’s Footsteps in Paris’ in the 22 September edition of the San Diego Union Tribune. My wife and I will be in Paris from 6 October to 11 October and we would like to hire Sheri to take us on the Jefferson tour. Please ask Sheri to send me an e-mail regarding the details of the tour.