John Baxter’s “Paris at the End of the World” – Patriotism transforming fashion (excerpt)

10 Thursday Apr 2014

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures

Tags

1933-1945 Anton Gill, A Dance Between the Flames: Berlin Between the Wars Anton Gill, A Pound of Paper John Baxter, An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler, Chronicles of Old Paris John Baxter, City of Light, Coco Chanel World War I, Cole Porter World War I, Constellation of Genius: 1922: Modernism Year One Kevin Jackson, Edith Wharton World War I Paris, Ernest Hemingway, Federico Fellini, French fashion during World War I, George Lucas, Immoveable Feast John Baxter, Jean Patou, JG Ballard, Josef von Sternberg, Luis Bunuel, Marcel Proust, Mayflower The Voyage from Hell Kevin Jackson, Pablo Picasso, Paris at the End of the World by John Baxter HarperCollins, Paris fashion during World War I, Paris Writers Workshop John Baxter, Paul Poiret, Robert De Niro, Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s John Baxter, The Most Beautiful Walk in the World John Baxter, The Paris Men's Salon John Baxter, The Perfect Meal John Baxter, The Regent Tailor Paris World War I, The Unknown Anzacs Michael Caulfield, Three Soldiers John dos Passos, Trench-art accessories World War I, Under Fire Henri Barbusse, Voices of War Michael Caulfield, We'll Always Have Paris John Baxter, Woody Allen, World War I

Share it

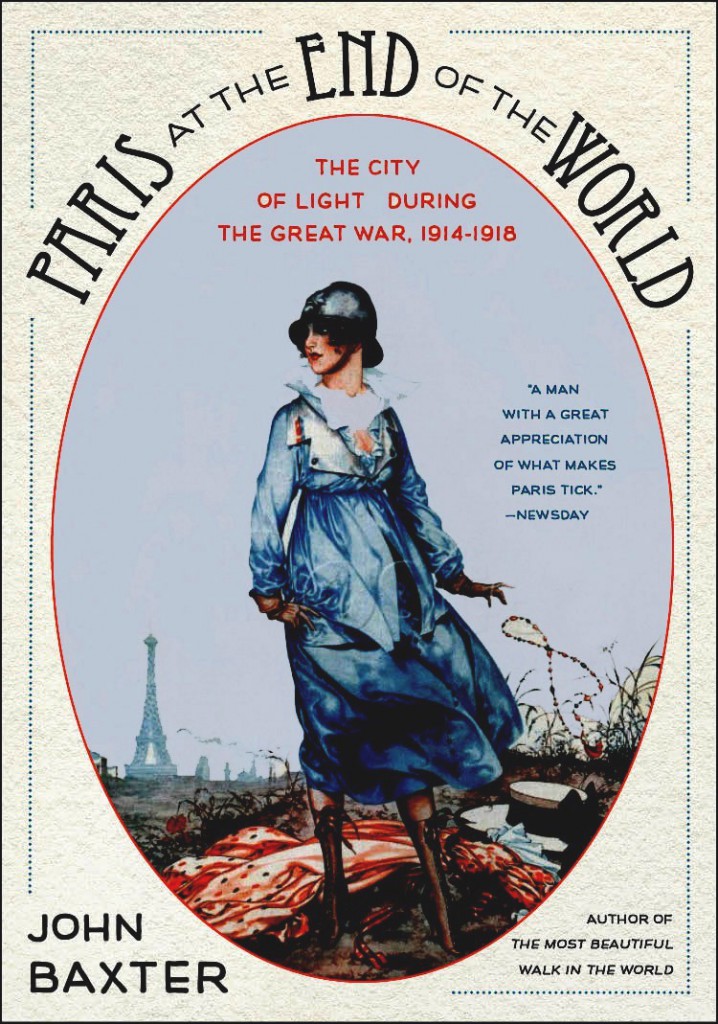

Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918 by John Baxter (Harper Perennial, April 15, 2014) excerpt from HarperCollins.

Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918 by John Baxter (Harper Perennial, April 15, 2014) excerpt from HarperCollins.

A preeminent writer on Paris, John Baxter brilliantly brings to life one of the most dramatic and fascinating periods in the city’s history. During World War I, the terrifying sounds of the nearby front could be heard from inside the French capital; Germany’s “Paris Gun” and enemy aviators routinely bombarded the city.

And yet in its darkest hour, the City of Light blazed more brightly than ever. Its taxis shuttled troops to the front; its great railway stations received reinforcements from across the world; its grand museums and cathedrals housed the wounded; and the Eiffel Tower hummed at all hours, relaying messages to and from the trenches. At night, Parisians lived with urgency and without inhibition, embracing the lush and the libertine. The rich hosted parties that depleted their wine cellars of the finest vintages. Artists such as Pablo Picasso achieved new creative heights. And the war brought a wave of foreigners to the city for the first time, including Ernest Hemingway and Baxter’s own grandfather, Archie, whose diaries he uses to reconstruct a soldier’s-eye view of the war years.

Uncovering a thrilling chapter in Paris’s history, John Baxter’s revelatory new book shows how this extraordinary period was essential in forging the spirit of the city we love today.

Interview: John Baxter on the First World War: A reflection on Paris’ history and transition during the war years, published on A Woman’s Paris®.

Chapter Twenty-four: “DRESSED TO KILL” by John Baxter

Imprisoned by asthma in his apartment at 102 boulevard Haussmann, Marcel Proust wrote at night, sleeping by day in his cork-lined bedroom, and only rising, if he got up at all, at four in the afternoon. He saw the war in fragments; glimpses through the windows of his closed car as his chauffeur, Odilon Albaret, a former cabbie and husband of his faithful housekeeper Celeste, drove him to some nocturnal rendezvous, sometimes in the glitter of the Ritz Hotel dining room on place Vendome, on other occasions to the small and squalid Hotel Marigny on rue de l’Arcade, a gay brothel managed by Albert de Cuziat. As Proust was a partner in the business, M. De Cuziat willingly accommodated his sadistic tastes, which “needed,” in the words of arch-gossip Cocteau, “the spectacle of a young Hercules slaying a rat with a red hot needle.”

Seeing the city in time-lapse alerted Proust to minute changes in style. Patriotism, he saw, was transforming fashion.

As the Louvre and all the museums were closed, when one read at the head of an article “Sensational Show”, one could be certain it was not an exhibition of pictures but of dresses. Just as artists exhibiting at the revolutionary salon in 1793 proclaimed that it would be a mistake if it were regarded as “inappropriate by austere Republicans that we should be engaged in art when the whole of Europe is besieging the territory of liberty”, the dressmakers of 1916 asserted, with the self-conscious conceit of the artist, that “to seek what was new, to avoid banality, to prepare for victory by developing a new formula of beauty for the generations after the war”, was their absorbing ambition.

With designers such as Patou and Poiret working for the army, smaller dress and hat-makers flourished, particularly if they could improvise. Deprived of feathers from Africa and the Caribbean, Coco Chanel adapted the simple straws and berets of her country childhood. Like almost everything she did, they started a trend and increased her reputation. With silk unobtainable, dressmakers scavenged what they could. Once it became known that each flare sent up to light no-man’s-land included a small silk parachute to slow its descent, soldiers on both sides risked their lives to retrieve them for their girlfriends back home. Two could be sewn into a pair of knickers, and four made a good-sized blouse.

Meanwhile, in Paris, shrewd designers suggested to their all-too-suggestible clients that it was their duty to dress well, so long as their clothes included some acknowledgment of the war. In a Baionnette cartoon, a dowager asks a couturier if selling expensive clothes in wartime is unpatriotic. “I not a patriot, baroness?” he replies indignantly. “But who created the gown in Pekin taffeta called ‘Croix de Guerre’, and the ‘Where Will It End?’ evening coat?” Proust noticed that

young women were wearing cylindrical turbans on their heads and straight Egyptian tunics, dark and very ‘warlike’. They were shod in sandals, or puttees like those of our beloved combatants. Their rings and bracelets were made from fragments of shell casings from the 75s, and they carried cigarette lighters consisting of two English half-pennies to which a soldier in his dug-out had succeeded in giving a patina so beautiful that the profile of Queen Victoria might have been traced by Pisanello.

Soldiers on leave in Paris, expecting to see many women in mourning, were told the custom of wearing black for a year after the death of a loved one had been allowed to slide – “the pretext being,” wrote Proust, “that [the deceased] was proud to die – which enabled them to wear a close bonnet of white English crêpe (graceful of effect and encouraging to admirers), while the invincible certainty of final triumph permitted them to substitute satins and silk muslins for the earlier dark cashmere, and even to wear their pearls.”

Better than trench-art accessories or having your dressmaker run up a military-looking costume was winning the right to wear a uniform. The first stop for anyone with the slightest connection to an ambulance service or to the armed forces was their tailor or dressmaker. The Regent Tailor on boulevard de Sebastapol offered to create “military uniforms in satin, suede, leather, whipcord, gabardine, khaki etc. Cut and styling beyond reproach.” For those who couldn’t afford made-to-measure, plenty of stores offered ready-to-wear. In Henri Barbusse’s novel Under Fire, a poilu on leave in Paris is dazzled by “the shop windows displaying fantastic tunics and kepis, cravats of the softest blue twill, and brilliant red lace-up boots.” The New America, a manufacturer of military wear in bulk, advertised “Wholesalers, department stores and tailors etc who would care to contact us will receive an immediate proposition that will allow them to double their business in a week.”

Edith Wharton, paying a visit to the front, noted the diversity of uniforms.

The question of color has greatly preoccupied the French military authorities, who have been seeking an invisible blue, and the range of their experiments is proved by the extraordinary variety of shades of blue, ranging from a sort of greyish robin’s egg to the darkest navy. But to this scale of experimental blues, other colors must be added; the poppy-red of the Spahis’ tunics, and various other less familiar colors – grey, and a certain greenish khaki, the use of which is due to the fact that the cloth supply has given out and that all available materials are employed.

The inconsistency of fabrics and the proliferation of uniforms from other countries and armies helped draft-dodgers to lose themselves. In Le Feu, five soldiers from the front notice that some of the men who appear, from a distance, to be soldiers, are actually wearing a kind of fancy dress. Arriving home on leave, writer Paul Truffau was as astonished by the gaiety of the women on the boulevards as by the dubious military credentials of their men.

The lighted department stores, the beautiful cars, the pretty girls in their little hats, high-heeled boots, rice powder, muffs and little dogs, and draft dodgers in beautifully tailored blazers and breeches that look like uniforms, but drip with gold braid brighter than anything on the jackets of real officers. Over and over, you see such sights, next to soldiers on leave who roam the boulevards in tin hats, muddy greatcoats and heavy boots.

In John dos Passos’s novel Three Soldiers, an American on leave is overwhelmed by the variety and quality of the uniforms in the cafes around the Opera, none of them damaged or stained by combat. “Serbs, French, English, Americans, Australians, Rumanians, Tcheco-Slovaks. God, is there any uniform that isn’t here? The war’s been a great thing for the people who knew how to take advantage of it.” Songwriter Cole Porter owned an entire wardrobe of uniforms. His friend Monty Wooley recalled “Porter had more changes than Marchal Foch, and wore them with complete disregard of regulation. One night he might be a captain of the Zouaves, the next an aide-de-camp.”

Young common soldiers embittered by their experience of the front found the city’s cynicism disgraceful. In June 1916, Gaston Biron wrote to his mother at the end of a leave, “You will probably be astonished to hear that it was almost without regret that I left Paris, but it’s the truth. I’ve noticed, like all my comrades who are left, that these two years of war have, little by little, made the civilian population selfish and indifferent, and that we and the other combatants are almost forgotten. So what could be more natural than that we become as distant as they are, and return to the front calmly, as if we had never been away?” In September, at Chartres, Biron died of wounds. He was thirty.

Praise for Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918

“The most original and unexpectedly beguiling account of the Great War I have ever read. John Baxter is one of the master storytellers of our age, and by telling the tale of his half-forgotten grandfather, plucked out of sleepy Australia and pitched into the European massacre, he has been able to re-create not only the all-too-familiar Hell of the trenches but also the Heaven of sex and food and hedonism that was Paris at the twilight of its golden age. A revelation, an adventure, a joy to read.” —Kevin Jackson, author of Mayflower: The Voyage from Hell and Constellation of Genius: 1922: Modernism Year One

“John Baxter’s latest book marks the centenary of the beginning of the First World War with an intimate memoir of his grandfather’s experiences of that war, into which he weaves a reflection on its history, together with an examination of a Paris in transition during the war years – a transition which transformed the city of Art Nouveau and the Belle Époque into the city of the Jazz Age, invaded by Americans fleeing Prohibition, and the city of Art Déco. All this is done with Baxter’s inimitable lightness of touch and conversational style, which often belies the profound knowledge he has of his adoptive city.” —Anton Gill, author of A Dance Between the Flames: Berlin Between the Wars and An Honourable Defeat: A History of German Resistance to Hitler, 1933-1945

“To produce a fresh take on World War One is a not inconsiderable achievement. To do so in a book that’s a joy for both head and heart is a triumph. Paris At The End Of The World is original, moving and revelatory. Read it.” —Michael Caulfield, Producer of Australians at War and In Their Footsteps, and author of Voices of War and The Unknown Anzacs

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is author of the memoirs The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, and Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918 (April 16, 2014). A native of Australia, he lives with his wife and daughter in Paris, in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is author of the memoirs The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, and Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918 (April 16, 2014). A native of Australia, he lives with his wife and daughter in Paris, in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

Since moving to France, John has published biographies of Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Josef von Sternberg, Robert De Niro and the author J.G. Ballard, as well as five books of autobiography, including A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. His most recent books are Chronicles of Old Paris and The Paris Men’s Salon, a selection from his uncollected prose pieces. John’s translations of Morphine, by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest and Fumée d’Opium, by Claude Farrère, have also been published by HarperCollins, the latter as My Lady Opium.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the internet in search of new acquisitions.

In 1974 John was invited to become a visiting professor of film at Hollins College in Virginia, U.S.A. While in the U.S.A, he collaborated with Thomas Atkins on The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, a highly successful book of scientific speculation, and wrote a study of director King Vidor, as well as completing two novels, The Hermes Fall and Bidding. (Facebook) (Website) (A Woman’s Paris Interview with John Baxter)

Selected Books by John Baxter

Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918. Harper Perennial, April 15, 2014

The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s. Museyon Inc., 2014

The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France. Harper Perennial, 2013

The Most Beautiful Walk in the World: A Pedestrian in Paris. Harper Perennial, 2011

Chronicles of Old Paris: Exploring the Historic City of Light. Museyon Guides, 2011

Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas. Harper Perennial, 2008

We’ll Always have Paris: Sex and Love in the City of Light. Harper Perennial, 2006

A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2005

Text copyright ©2014 John Baxter. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com