John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “PABLO PICASSO”: In a Season of Calm Weather… (excerpt)

14 Tuesday Jul 2015

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Cultures

Tags

Aix-en-Provence Paul Cézanne, Antibes France, Antigone Jean Anouilh, Ashes of Roses Pablo Picasso, Brigitte Bardot, Cannes France, Chagall, Château de Vauvenargues France, Château Grimaldi Musée Picasso, Chilean artist Manuel Ortiz de Zárate, Christoph Grunenberg Kunsthalle Bremen, Claude Picasso, Côte d'Azur, Daley Plaza Chicago 1967, Dora Maar, France, Françoise Meunier, French artists, French culture, French Riviera, French Riviera and Its Artists John Baxter Museyon, French Riviera art literature love life Côte d'Azur, Georges Braque, Gerald Sara Murphy, Hyères France, In a Season of Calm Weather Ray Bradbury, Jacqueline Roque, Jean Cocteau, Jerome Brierre, Jonas Salk, La Californie France, Léger, Les Demoiselles d ’Avignon Pablo Picasso, Lydia Sylvette David, Man Ray, Marie-Laure Charles de Noailles, Marina Picasso, Mas de Notre-Dame du Vie Mougins France, Matisse, Mont Sainte-Victoire, Mougins France, Musée Picasso Paris, Olga Khokhlova, Pablito Picasso, Pablo Picasso, Paloma Picasso, Paris, Paulo Picasso, Pavillon de Flore, Peace Chapel National Picasso Museum, Picabia, Roger Vadim, Sylvette David, Thérèse Walter, Vallauris France, Vence France, Villa Santo-Sospir French Riviera Côte d'Azur

Share it

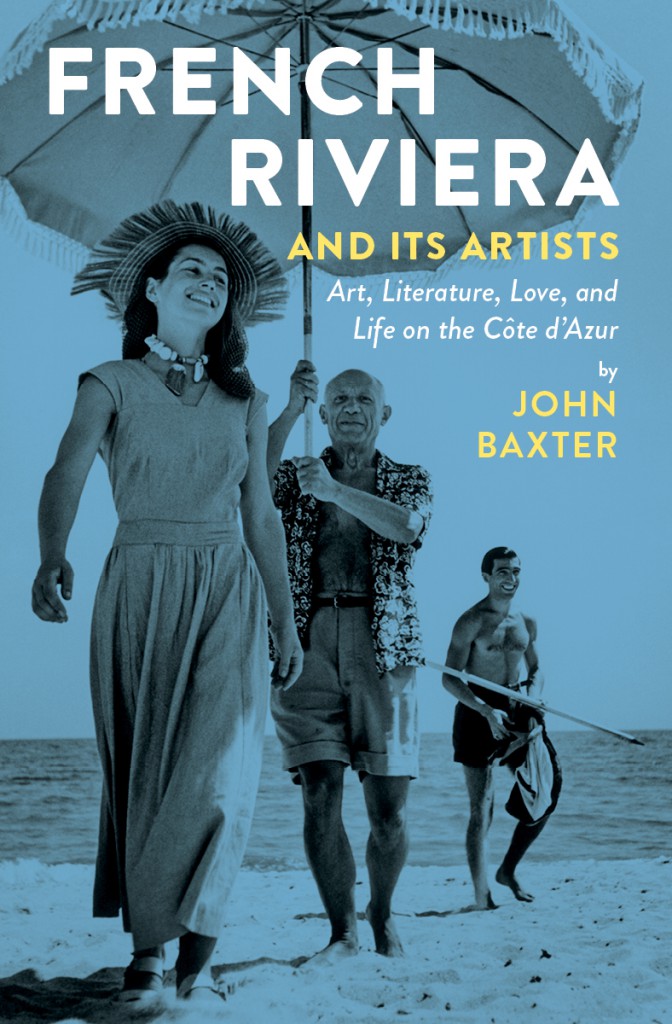

Excerpt from French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur – “PABLO PICASSO”: In a Season of Calm Weather… (excerpt), by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Museyon. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur – “PABLO PICASSO”: In a Season of Calm Weather… (excerpt), by John Baxter. © John Baxter. Reproduced by permission of Museyon. All rights reserved.

Get swept up in the glitz and glamour of the French Riviera as author and filmmaker John Baxter takes readers on a whirlwind tour through the star-studded cultural history of the Côte d’Azur that’s sure to delight travelers, Francophiles, and culture lovers alike.

For jesters and armchair travelers alike, French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur is sure to become an instant classic and will make even the most dedicated home-bodies yearn for the land of cafés and literary greats. (July, 2015, Museyon) (Purchase)

Praise for French Riviera and Its Artists

“These luminaries celebrated life and created art amid paradise and this book is the ultimate guide to the Riviera’s golden age.” —Christine Gray, luxurytravelmagazine.com

“As with all Museyon guidebooks, the volume is richly illustrated: The back matter alone features an art gallery of the French Riviera and its artists, but paintings are interspersed throughout the book.” —June Sawyers, Chicago Tribune

Subscribers, French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur by John Baxter bestselling author of The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, and We’ll Always Have Paris. Free book giveaway to two subscribers ends July 15, 2015.

Free Subscription: Join our thousands of followers to receive your copy of our Readers’ Choice: 253 Books About France, including books about Architecture, Interiors and Gardens; Arts; Biography; Children; Culture; Fashion; Food and Wine; Memoir; Mystery; Novel; Science; Travel; and War, along with email notifications of new posts on the website.

Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. We never sell or share member information.

Excerpt: John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”: Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir published with permission by A Woman’s Paris®.

Excerpt: John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “MANY FÊTES”: The Hôtel du Cap and Tender Is the Night published with permission on A Woman’s Paris®.

Interview: French Impressions: Author John Baxter and Editor Janice Battiste – conversations on the evolution of the book, “French Riviera and Its Artists” on A Woman’s Paris®.

French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur (excerpt)

“PABLO PICASSO”:

In a Season of Calm Weather…

by John Baxter

In 1959, fantasy writer Ray Bradbury published the short story In a Season of Calm Weather. It describes an enthusiast for Pablo Picasso who visits the Riviera in hopes of meeting him. Walking on the beach one evening, he does indeed run into the artist, out with his dog, but doesn’t speak—simply watches in wonder as Picasso, using nothing but a small stick, idly scratches a riotous frieze of nymphs and satyrs in the wet sand. But his delight has a downside. With no way to preserve the work, the man must resign himself to letting the waves wipe it out. Back in his hotel, he sits at the window, listening. When his wife asks what he hears, he says “Just the tide, coming in.”

Bradbury focuses on one quality that separated Picasso from other artists—his prodigality. The image of him scratching a masterpiece in wet sand was no great stretch. Creativity oozed from every pore. He not only produced more original and adventurous work than any contemporary—a total of tens of thousands of items—but did so in almost every medium: oil on canvas, ink on paper, etching, ceramics, and lithography. Confronted by a table covered in soft clay pots, he could twist, mold, and pinch them into different forms—doves, fish, women—leaving them to be glazed and fired by assistants. Tin cans, wire and scrap metal, bent and soldered together, were transformed into a menagerie of animals. He sketched on menus, tablecloths, and matchbooks. He might pay a bar bill by scribbling a portrait or corrida scene on the verso. In 2010, an electrician produced a cache of 241 paintings, which he claimed Picasso gave him in payment for house improvements.

It became a point of honor to let no artistic challenge go unanswered. Chilean artist Manuel Ortiz de Zárate, having fallen on hard times, took to Picasso his nest egg, an ingot of gold, in hopes he’d buy it. Picasso asked for a few days to consider. In that time, Picasso, according to writer Paul Bowles, “was feverishly studying the essentials of the goldsmith’s craft, one of the few which he had until then neglected. He smelted the gold, made it into a small, rather Aztec-looking mask with features in relief, and engraved his signature on the back.” When Ortiz returned, Picasso presented him with the mask, worth many times the value of the raw metal.

Picasso moved house as often as he changed companions. The key to his restlessness was women. “He loved women and used them in order to be creative,” says his granddaughter Marina. Long-time mistress Françoise Gilot sarcastically compared him to legendary wife-murderer Bluebeard: she would not have been surprised, she said, to open a wardrobe in his home and find the bodies of her predecessors hanging there. With Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso spent more time in the Normandy resort of Dinard. With his first wife, Olga Khokhlova, and such companions as Dora Maar, his home was Paris, but with his last wife, Jacqueline Roque, and with Gilot, his preferred milieu was the Riviera.

Each move, like each woman, brought fresh inspiration. His earlier work, in particularly the Cubism he developed with Georges Braque, shows a metropolitan sophistication in its use of a city’s detritus—newspapers, advertising signs, sheet music. However his ceramics, redolent of ancient Mediterranean trade, his images of the bullfight, the romping giantesses of his décor for the ballet Le Train Bleu (1924), his co-opting of Greek mythology in his use of the Minotaur myth to symbolize his own waning potency, and of Provençal whorehouses in Les Demoiselles d ’Avignon (1907) to celebrate the carnality of bought sex—all these bear, as if seared into them, the imprint of a Mediterranean sun.

In 1936, Picasso rented a house in Mougins, a village built on the ruins of a Roman settlement in the hills behind Cannes. He was visited there by such artist friends as Picabia, Cocteau, Léger and Man Ray, all of whom spent summers in the south, often at the nearby homes of Marie-Laure and Charles de Noailles in Hyères or at the Villa America of Gerald and Sara Murphy in Antibes, where Picasso would often join them.

When his Mougins landlord, ignorant of his fame, protested his habit of painting on the walls, Picasso found new working space in Antibes. In 1946, with his newest mistress Françoise Gilot as assistant, he decorated an entire floor of the Château Grimaldi—today the Musée Picasso. In 1948 he moved with Gilot to Vallauris, a Communist-governed town in the hills above Cannes, and there he created murals for a deconsecrated chapel disused since the Revolution of 1789. Described optimistically as a “Peace Chapel,” the building and its belligerent frescos channeled Picasso’s personal turmoil into a protest on behalf of the town and the Communist party against the war in Korea. They are also an atheist’s wry comment on the two Catholic chapels in nearby Vence, decorated by Matisse and Chagall. The Peace Chapel is now a part of the National Picasso Museum. Gilot left him, taking their two children, in 1953—the only of his partners to do so.

In Vallauris, Picasso fell under the spell of yet another woman in the spring of 1954. Nineteen-year-old Lydia Sylvette David caught his eye when she helped her furniture-designer boyfriend deliver some chairs to Picasso’s villa, La Galloise, in the hills outside town. Long-necked, slim and blonde, Sylvette wore her hair in bangs and a long ponytail high on the back of her head, a look inspired by ancient Greece by way of a recent Paris stage production of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone (1944).

Picasso, captivated, asked her to sit for him, and began work on what became a series of sixty drawings, paintings, and sculptures. She insists she was too timid to pose nude or become his lover. Christoph Grunenberg, director of Germany’s Kunsthalle Bremen, which has exhibited some of the series, suggests this could have fuelled Picasso’s inspiration. “Maybe it was her resistance to be seduced by him that made him need to see her: because he didn’t conquer her, he needed to conquer her on canvas and on paper and in sculpture.” Denied her naked body, Picasso concentrated on externals; her ponytail, the innocent wide-eyed pout, even her then-fashionable hooded coat with large buttons down the front. Echoes of her would continue to appear in his later work, including the fifty-foot-tall sculpture installed in Daley Plaza in the center of Chicago in 1967.

In 1955, Picasso moved to a tumbledown mansion above Cannes called La Californie. Built in 1920, it became his holiday home and a storehouse for both his own work and that given to him by others. After his death, more than 500 canvases, his personal archive, going back to his childhood in Spain, were removed from the villa. They became the basis of the collection now housed in the Musée Picasso in Paris.

It was at La Californie in 1956 that the artist encountered another twentieth-century icon, Brigitte Bardot. With her pout and high ponytail, the actress strikingly resembled a more knowing version of Sylvette David—no accident, says David, who claims Bardot and her director Roger Vadim copied her. “I only had one brief meeting with Brigitte Bardot, when we passed each other on the promenade at Cannes during the film festival of 1954. She was on Vadim’s arm and I was on Picasso’s, and of course we took a long look at each other and the men took a long look at us. The next time I saw her, she was no longer a brunette but had dyed her hair blonde to match mine, keeping the fashionable dark eyelashes. She had adopted the ponytail, but really it wasn’t as stylish.” Although photographer Jerome Brierre covered the meeting of Bardot and Picasso for Life magazine, Picasso never painted Bardot. In her version, she was too shy to ask. Others suggest she did offer, but Picasso, faithful to Sylvette, turned her down with a curt “I only have one model at a time.”

La Californie was no luxury residence. Some rooms, including the kitchen, remained floored in earth, and animals, among them a goat, wandered in and out at will. Picasso himself slouched around in baggy t-shirts and shorts. He made no concessions to visitors, least of all to his grandchildren Marina and Pablito, who lived in poverty in Cannes with their grandmother, Olga. Their father Paulo, who, as a boy, had modeled for Picasso as a sad-eyed clown, lacked artistic talent. He preferred automobiles, and wanted to open a garage, but his father, embarrassed, made him his chauffeur instead. Humiliated, Paulo became an alcoholic, and died young.

When Marina and Pablito needed money, they were told to ask their grandfather. He often left them standing at the gate for hours, then sent his housekeeper to inform them that “the Master” was too busy to see them. Picasso only took an interest when Marina became a pretty adolescent.

In 1958, Picasso acquired the Château de Vauvenargues, in the countryside near Aix-en-Provence immortalized by Paul Cézanne. “I have just bought Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire,” he boasted to friends. Thinking he meant one of the artist’s canvases of the mountain, they asked, “Which one?” “The real one!” Picasso snapped in exasperation.

The château’s remote location and imposing architecture reminded Picasso of his birthplace in Spain. Intending to spend the rest of his life there, he installed a number of bronze figures on the terrace and transferred hundreds of paintings from other houses. However, his last wife Jacqueline Roque found it too isolated and draughty, so after only two years they moved to Mas de Notre-Dame du Vie in Mougins, where he lived his last twelve years, and died in 1973. When the authorities at Mougins refused to let him be buried in the garden, he was interred at Vauvenargues.

While Picasso lived, Jacqueline had been his strict, indeed fanatical protector. Even after they married, she continued to address him as “Master,” and even “Soleil”—Sun. She barred many members of the family from the funeral, claiming he would not have wanted them there. They included Paloma and Claude, his children by Françoise Gilot, and former mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. She also turned away Pablito and Marina.

Following Picasso’s death, bad luck dogged the family. Shortly after the funeral, Pablito killed himself by drinking bleach. In later years, Jacqueline Roque, Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar also committed suicide. Picasso always refused to make a will, gleefully anticipating that his heirs would fight over his millions. He might have been surprised by the result. Backed by the fortune of her husband, American biologist Jonas Salk, Françoise Gilot forced a change in the law, permitting both legitimate and illegitimate children to share an inheritance. Her son Claude later became chief administrator of his father’s legacy.

Ironically, La Californie, as part of Paulo’s inheritance, passed to Marina, the grandchild Picasso once scorned. Renamed Pavillon de Flore, it has become a showcase. Among the works hanging there is his pensive portrait of the mentally unstable Olga. If guilt has a color, it is that of her dress in the painting, the greyish pink known as Ashes of Roses, emblematic of her troubled life, and, some might say, of the way Picasso consumed women in the fire of his genius.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, and Five Nights in Paris. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is the author of the memoirs: The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, The Golden Moments of Paris: A Guide to the Paris of the 1920s, Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, and Five Nights in Paris. A native of Australia, he currently lives with his wife and daughter in Paris—in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

Since moving to France, John has published biographies of Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Josef von Sternberg, Robert De Niro, and the author J.G. Ballard. He has also written five autobiographies, including A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. His most recent books are Chronicles of Old Paris and The Paris Men’s Salon, a selection from his uncollected prose pieces. John’s translations of Morphine, by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest and Fumée d’Opium, by Claude Farrère, have also been published by HarperCollins, the latter as My Lady Opium.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker at universities and writers workshops. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the internet in search of new acquisitions.

In 1974, John was invited to become a visiting professor of film at Hollins College in Virginia, U.S.A. While in the United States, he collaborated with Thomas Atkins on The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, a highly successful book of scientific speculation, and wrote a study of director King Vidor, as well as completing two novels, The Hermes Fall and Bidding. (Facebook) (Website)

Photo: Rudy Gelenter

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “THE WALLS SPEAK FOR ME”: Jean Cocteau and the Villa Santo-Sospir (excerpt). Graphic artist, playwright, poet, novelist, film director—Jean Cocteau was too multi-talented for his own good. In a period characterized by commitment and specialization, his contemporaries scorned his failure to join some movement or embrace a cread. Cocteau felt himself to be above petty categorizations. He preferred to echo Oscar Wilde, who, on being asked by U.S. Customs if he had anything to declare, is said to have replied, “Only my Genius.”

John Baxter’s “French Riviera and Its Artists” – “MANY FÊTES”: The Hôtel du Cap and Tender Is the Night (excerpt). “On the pleasant shore of the French Riviera, about half way between Marseille and the Italian border, stands a large, proud, rose-colored hotel. Deferential palms cool its flushed façade, and before it stretches a short dazzling beach. Lately it has become a summer resort of notable and fashionable people,” begins Scott Fitzgerald in his book Tender Is the Night, the finest of all Riviera novels, with this description of the Côte d’Azur’s most exclusive hotel.

French Impressions: Author John Baxter and Editor Janice Battiste – conversations on the evolution of the book, “French Riviera and Its Artists”. “Writers interviewed by the media or at festivals often describe the crucial moment they decided to write a book,” writes John Baxter. “In my experience, such moments seldom exist.” John never set out to write a book about the French Riviera and its artists. The idea caome from a New York publisher, Akira Chiba, who owns a small company called Museyon. Akira handed editing of the book to a trusted collaborator, the free-lance editor Janice Battiste. Janice and John had worked with great congeniality on The Golden Moments of Paris, so it was a pleasure for them to set out again. The extracts from John and Janice’s emails synopsize the process by which they jointly brought The French Riviera and Its Artists to a successful conclusion.

Je suis Charlie: “Paris Mourns Heros of the Pen” by Ronald C. Rosbottom. Ronald C. Rosbottom, author of the bestseller When Paris Went Dark, is the key person to talk about Paris having gone dark once more considering the tragic attack at the Charlie Hebdo headquarters in early 2015. Ronald’s letter to colleagues and friends captures the terror and humiliation that was Paris. We feel When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944, is timelier than ever.

Gerri Chanel’s “Saving Mona Lisa” on the battle to protect the artistic heritage of France during World War II (part one). In this engaging and suspenseful book, Gerri Chanel describes the connections between the museum and its curators to other wartime developments in France. Superbly researched, Saving Mona Lisa is a compelling true story of art and beauty, intrigue and ingenuity, and remarkable moral courage in the face of one of the most fearful enemies in history.

The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 – Excerpt from Ronald C. Rosbottom’s “When Paris Went Dark” (Part One). June 14, 1940, German tanks entered a silent and deserted Paris and The City of Light was occupied by the Third Reich for the next four years. Rosbottom illuminates the unforgettable history of both the important and minor challenges of day-to-day life under Nazi occupation, and of the myriad forms of resistance that took shape during that period. August 2014 marks the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris, perfect timing for Ronald C. Rosbottom’s riveting history of the period.

The Impossible Legacy of the Perfect Parisian Woman by Edith de Belleville, who is both French and Parisan to the core, unites the past and present in her exploration of the Parisian myth: the perfect French woman. The Parisian woman, writes Edith, is not just the cold image of a fragile and chic fashion plate on high heels. Being Parisian is a behavior in life. The unique, violent, and bloody history of Paris built the soul of the Parisian who has a strong personality and is proud of the beloved city she fought for.

Text copyright ©2015 John Baxter. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com

1 comments

Jacqueline Bucar said:

July 14, 2015 at 4:51 pm

I knew Picasso was not a “family man” but there is so much in this article that I had no idea about. Incredible portrait of Picasso. How does a man sensitive enough to paint the horrors of war including many subtleties of that horror in a masterpiece like Guernica be such an unfeeling father and grandfather? I wondered about jealousy among artists and if he was jealous of other great painters like Cezanne whose influence can be seen in so many of them including Picasso.