French Impressions: Meg Bortin’s “Desperate to Be a Housewife” on the challenges of being a woman in our time (part one)

16 Monday Dec 2013

A Woman’s Paris™ in Interviews

Tags

Agence France-Presse AFP, American women, Associated Press, Bruno Chief of Police by Martin Walker, Cuban missile crisis, Desperate to Be a Housewife by Meg Bortin, everydayfrenchchef, France, French women, Gorbachev USSR, Le Divorce by Diane Johnson, Meg Bortin, Memoir, Mirabelle Books, Paris, Reuters, The Cold War, The Cold War: A History by Martin Walker, The International Herald Tribune, The Moscow Times, The New York Times, United Press International, University of Wisconsin, Vietnam protests

Share it

(Part two) Meg Bortin is an American journalist and writer based in Paris. Her articles on politics, culture and lifestyle have appeared in The International Herald Tribune, The New York Times and many other publications. A former senior editor at the International Herald Tribune, she has written widely on French and Soviet affairs. In 1992, she was the founding editor of The Moscow Times, the first independent English-language daily newspaper in Russia. Her personal essay Dear Djeneba was included in Family Wanted, an anthology on adoption published by Granta Books in 2005 and Random House in 2006. As a food blogger, she posts recipes regularly at www.everydayfrenchchef.com. She and her daughter divide their time between Paris and Burgundy, where they have a garden.

(Part two) Meg Bortin is an American journalist and writer based in Paris. Her articles on politics, culture and lifestyle have appeared in The International Herald Tribune, The New York Times and many other publications. A former senior editor at the International Herald Tribune, she has written widely on French and Soviet affairs. In 1992, she was the founding editor of The Moscow Times, the first independent English-language daily newspaper in Russia. Her personal essay Dear Djeneba was included in Family Wanted, an anthology on adoption published by Granta Books in 2005 and Random House in 2006. As a food blogger, she posts recipes regularly at www.everydayfrenchchef.com. She and her daughter divide their time between Paris and Burgundy, where they have a garden.

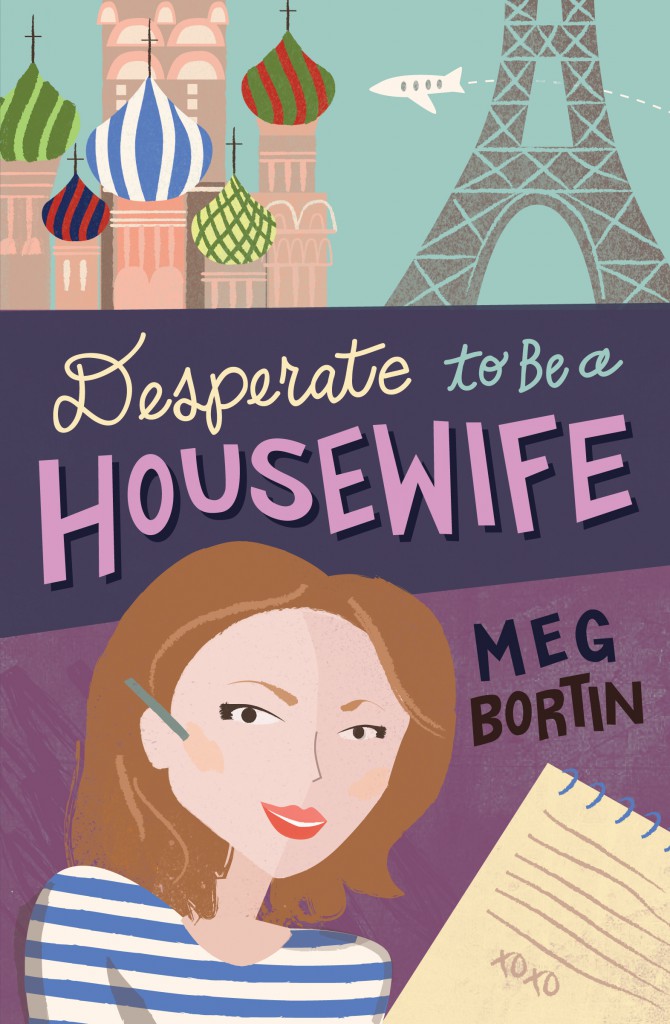

Desperate to Be a Housewife, Meg Bortin’s second book, was published by Mirabelle Books in 2013. Her first, Dear Djeneba, was included in Family Wanted, an anthology on adoption published by Granta Books in 2005 and Random House in 2006. For more information on Meg Bortin, visit: (Website) (Facebook) (Purchase)

Desperate to Be a Housewife, Meg Bortin’s second book, was published by Mirabelle Books in 2013. Her first, Dear Djeneba, was included in Family Wanted, an anthology on adoption published by Granta Books in 2005 and Random House in 2006. For more information on Meg Bortin, visit: (Website) (Facebook) (Purchase)

Photo credit: Marion Kalter

“Tear Gas and U.S. college riots in the ’60s, Paris and love in the ’70s, Gorbachev’s Moscow and Afghan missiles in the ’80s, Meg Bortin—aka Mona Venture—saw it all, did it all and wrote it all up, while enjoying serial love affairs and a lot of great meals along the way. More than a thrilling memoir, this is also an enthralling book about sex, love and the evolving challenges of being a woman in our time.” — Martin Walker, author of The Cold War: A History and the Bruno, Chief of Police mystery novels.

“Meg Bortin’s eventful memoir will surprise and amuse.” — Diane Johnson, author of Le Divorce

INTERVIEW

“Ay, now am I in Arden; the more fool I; when I was at home, I was in a better place: but travelers must be content.” — William Shakespeare

Desperate to Be a Housewife

AWP: You are the author of Desperate to Be a Housewife. What inspired you to write this book?

MB: I felt that my experience as a woman who came of age at a very specific moment in history might have resonance for other people. The very heady days of the late ’60s in the States – the Vietnam protests, sexual revolution and the start of the women’s movement – have of course been widely covered in novels and essays. But having left the States for France, and then Gorbachev’s USSR, I felt I could add another dimension to this chapter of history. It was a time when many others were torn, as I was, between the independence I’d carved out and my longing for happily-ever-after.

AWP: In Desperate to Be a Housewife, you capture insights into the human spirit and the bittersweet tension between your travel companions, lovers, and yourself. What were the challenges and how did you unfold the story you wanted to share?

MB: The main challenge was to be true to the story. Even though I changed the names of the people portrayed, Desperate is nonfiction and all the events recorded actually took place. Many readers have asked why I didn’t turn it into a novel – but I felt the fact that it was a true story was what gave it its strength. Nonetheless, it was quite difficult to describe the conflicts I experienced in a way that was fair – both to myself, and to the men and women in my life, regardless of what happened between us. After the opening chapter, which sets the scene, the story flashes back and unfolds chronogically. That was the easiest part.

AWP: You write about love. “Loves me, loves me not,” the United States version of effeuiller la marguerite, a game of French origin played while plucking one petal off a flower, usually a daisy, for each phrase. But in France, plucking marguerites has six choices: Il m’aime, un peu, beaucoup, à la folie, passionnément, pas du tout (he loves me, a little, a lot, madly, passionately, not at all). What was the most surprising thing you learned about each culture as it codifies passion and romantic love?

MB: I hope American readers of this interview will forgive me, but the French seem to have fewer complexes about love than we do. Or is it just speaking a foreign language that makes it feel so much easier to say ‘Je t’aime’ than ‘I love you’? The French seem to take affairs of the heart more lightly than we do. Flirting is constant, and what they call the cinq à sept – 5 to 7 p.m., when lovers tryst before going home to their families – is a national sport. Of course not everybody indulges in this, but the French have a libertine tradition that goes back centuries. It is not at all uncommon to see couples kissing passionately in public. As an American friend who visited me in Paris once remarked many years ago, ‘I saw a couple on the metro doing things I wouldn’t do in the bedroom!’ It’s just a sexy place. There’s also more elegance in the way people talk about love and desire. Where an American man might say, ‘Do you want to go to bed?’ a Frenchman would be more likely to take your hand and lead you there, saying, ‘I desire you, my love.’ Which is one of the sexiest things a woman can hear.

AWP: In Desperate to Be a Housewife, you lead readers beyond exotic geography and into the rich terrain of the human heart. What is that image, rich terrain of the human heart, like?

MB: It’s a place where anything can happen – and if you open yourself to love, you can find yourself in a transcendent state, not just as a teen but in maturity, too. Of course, the heart can also break. So it’s a very vulnerable terrain.

AWP: Your memoir, for the most part, takes place in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, several decades before you published Desperate to Be a Housewife, in 2013. Did you feel a need to share this particular time and place today?

MB: Yes. I felt that the temporal distance made it easier to understand a period that was exhilarating but also very confusing at the time. And I wanted to record this period both for people of my generation, who may have had similar experiences, and for younger readers who missed out on a chapter that has transformed what we expect of our political leaders and the way we regard relations between the sexes.

AWP: In this memoir, what beckoned you to see behind the veil of ordinary Western culture: in particular, its U.S. college riots in the ’60s, Paris and love in the ’70s, Gorbachev’s Moscow and Afghan missiles in the ’80s, and events leading to the collapse of the Cold War? Did you feel you were witnessing the start of a new era?

MB: Yes. I felt it at the time, and I still feel that way today. As for seeing behind the veil, my career as a journalist – a professional observer of the world around me – taught me to look beneath the surface of events for a deeper understanding.

AWP: What was your “Cold War” upbringing like in Wisconsin?

MB: I was 12 at the time of the Cuban missile crisis, and remember looking out the window of the school bus to see whether there were any Russian nuclear bombers flying overhead. At school we had daily drills where, at the sound of a loud alarm bell, we had to run into the corridors and sit along the wall with our arms over our heads – as though that would protect us from a nuclear strike. Neighbors built bomb shelters, and everyone stocked up on canned food, thinking this could see us through an emergency, nevermind the radioactive fallout. Down the highway from our home was a Nike site, with nuclear-tipped missiles ready for launching. All of this was terrifying, but ultimately led me to want to go to Russia – where, I learned, people my age had experienced similar fears and were equally curious about ‘the enemy.’ It was extremely gratifying to be in Moscow when the Cold War finally began to ease.

AWP: Do you feel there are things that haven’t been said about the cultural revolutions in the ’60s and ’70s in America and France that you are trying to explore in your work now?

MB: So many people have written so eloquently on this subject that I don’t think I’m adding anything new, in terms of the events. What I did feel I had to offer was the way these enormous changes played out in the life of one woman. It’s a personal perspective that, hopefully, illuminates the era in a new way.

AWP: What do you think it is about the book Desperate to Be a Housewife that makes readers connect in such a powerful way?

MB: It may be because of the everywoman quality of the heroine – my alter ego, Mona Venture. Her misadventures are of the kind that everyone can identify with. She is chatty and down-to-earth, and has a humorous perspective on life. She doesn’t make a big deal out of her various catastrophes, romantic and otherwise, which may, oddly, make them more powerful.

AWP: An underlying theme in books about women and France is the message of freedom for women to experience their different selves or codify an articulate self. Why is this message significant, especially for women today?

MB: Fifty years after the start of the women’s movement, so many of us still have a hard time feeling free to become the women we want to be. We are still bound by so many conventions. It’s very challenging to let go of the fear of social reprobation if we defy these conventions in order to follow our hearts. In my view, this is equally true for French and American women. And women in both countries still face not just reprobation, but discrimination in the workplace. Equal pay for equal work is still largely a fiction, and the glass ceiling has only started to be cracked. Nonetheless, French women often appear to have an easier time than American women in living life as they desire it instead of attempting to conform to what is expected of them. The French have an expression that has no obvious equivalent in English. They will say of a woman, ‘Elle est très épanouie’ – meaning she’s radiant, fluorishing, happy. The subtext is that she has taken control of her life and is reaping the benefits, sexually, professionally and otherwise. The expression derives from the word s’épanouir, which connotes the way a budding flower will open up in the sun. As women, we need to remember to allow ourselves this pleasure – to take control of our lives in order to blossom.

WRITING

AWP: Your career has taken you from copy editor at Agence France-Presse (AFP) to foreign correspondent for Reuters, founding editor of The Moscow Times and senior editor at the International Herald Tribune to the world of autobiographic memoir. What inspired you toward a life and career so dependent on words and the ability to communicate?

MB: My father was a great story-teller. He was also a physician of great compassion. I admired these qualities while growing up. My mother was a lover of the arts and literature who occasionally wrote for a small local paper. Her example also inspired me. I studied literature at the University of Wisconsin, but my main education there was in the streets as I became caught up in the political movements of the times – the protests against the Vietnam war, the struggle of blacks for civil rights, the fledgling movement for women’s liberation. Upon graduation, I wanted to play a role – even a very small role – in making the world a better place, more fair, more just, but didn’t know how to achieve this. Then one day I had the great good fortune to fall into journalism. As reporters and editors, using words to bring events into the public eye, journalists can help readers better understand a complex world. Only with this understanding can we make progress toward righting the wrongs of our societies. So much remains to be done, and communication is essential.

AWP: The Western news organizations AP, Reuters, UPI, and AFP are often referred to as the “big time” of big-name columnists. What was it like working there?

MB: It was a hugely fun, and also hugely challenging because as a news agency reporter you are in competition with the other wire services. You need to be very fast, but also very accurate. Otherwise you risk receiving a ‘rocket’ from your editor blasting you for being beaten by the other wires. It was a great training ground for learning the trade of writing. My colleagues were also a fabulous crowd – passionate, intelligent, funny people with a great lust for life. They taught me so much.

AWP: Your career has taken you to France, London, and Russia as senior editor and foreign correspondent. How would you describe your life, on assignment, as a solo traveler?

MB: Well, given that I wanted to be married with children, life as a solo traveler was a lonely business at times. On the other hand, I was free to go off as an adventurer and was lucky enough to find myself on the front lines of some truly world-changing events. It was immensely exciting, and the opportunity to live and work in different cultures has been a very mind-expanding experience.

AWP: AWP: Do you feel you’ve brought a journalist’s point of view to the writing of memoir?

MB: Yes. In the sense that I tried to tell the story very accurately, and to present the events I recount as objectively as possible. I hope I’ve succeeded in this. But the very liberating thing about literary writing is that subjectivity is also part of the process. When writing about human relations, I could say take a point of view, and not have to maintain the guise of the objective observer.

AWP: What is the most surprising thing you’ve learned as a memoirist?

MB: That despite having a notoriously terrible memory in everyday life, I have the capacity to plunge into the past and recreate events that took place decades ago.

AWP: Could you talk about your process as a writer?

MB: When I was working on the memoir, I would get up early every morning, see my daughter off to school, do the necessary minimum of housework, and then sit down to write. It was like entering a time-machine. As I sat at my computer, the present faded out and I re-entered the particular moment in time I was writing about. Everything came back – sights, sounds, smells, feelings. And then it was as though some external force was guiding my fingers as they typed it all down. I didn’t have to think too hard, at least not while writing the first draft. I just let the past flow through me and transfer itself to the page, usually for two to three hours. After that, I came back to the present, with no more energy for writing that day. It’s so all-consuming that it leaves you emptied. Then, once the first draft was written, I went back and revised many times. That was a lot more work.

AWP: Do you keep a journal? Is there the temptation to keep a journal just to preserve what you’ve experienced?

MB: No. I have never kept a journal, although there were times when I thought I should, particularly in the Soviet Union when a closed society began opening up thanks to Gorbachev’s reforms. It was an incredibly exciting time, and very moving. But in the end, life took precedence over art. In terms of preserving what I’ve experienced, I very much regret having not kept a journal after adopting my daughter. I would so love to have a record of her astonishing early years. But I was a single mother with a full time job, and there just wasn’t time for that.

AWP: In general, what opportunities or challenges do you experience as an American writer in France?

MB: This is such an aesthetic culture with such a strong literary tradition that it’s inspiring simply to live here. I also feel that writers who live abroad have the benefit of a certain critical distance from their homegrown assumptions. You get a stronger depth of vision by being able to view the world from two different angles.

AWP: What is it about Paris and writers?

MB: A fabulous cosmopolitan city, its transcendent beauty, its style, its energy, the poetry of everyday life. A city big enough to allow you to be anonymous, small enough to ensure you never feel lost. A new discovery around every street corner. The café culture, the history, the romance, the savoir-vivre – the feeling that you are not merely allowed but actually expected to get the greatest possible pleasure from life. The value Parisians place on intellectual life and critical thinking. Their love of books. The freedom to be who you want to be. These all add up to creating a very rich environment for anyone wishing to lead the writer’s life.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post Finding boubous, taibas, and myself in Sénégal, by Ashley Steele, an African American and student of French, who wanted to explore a non-Western culture and its perspective where she found a deep meaning once she stepped foot on African soil. (French)

French Impressions: Paula Butturini on writing, adversity, and finding grace in asparagus. Paula, following her work as an East European correspondent based in Warsaw and freelance writer for The New York Times, Boston Globe, San Francisco Examiner, Houston Chronicle, Miami Herald, Washington Post and Baltimore Sun, left journalism to resume writing her book, Keeping the Feast: One Couple’s Story of Love, Food, and Healing. Keeping the Feast, is an extraordinary story of family and place—following her husband’s shooting, recovery and rehabilitation; and the immediate restorative pleasure of a single Italian meal.

What’s in a Word? There’s more to French class than you thought. Jacqueline Bucar, French teacher and immigration attorney, invites us to stimulate a way of thinking and learning that expands our understanding of the world and ourselves through the study of a foreign language. She shares “what’s in a word,” a way of thinking, a “mentality” that helps define the people who speak it and their culture. (French)

Vive La Femme: In defense of cross-cultural appreciation. Writer Kristin Wood finds Francophiles around the world divided by Paul Rudnick’s piece entitled “Vive La France” in the New Yorker magazine. As is often the case with satire, there is a layer of truth to the matter that is rather unsettling. Including comments from readers worldwide. (French)

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2013 Meg Bortin. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com