French Impressions: John Baxter’s “The Perfect Meal” and Finding the Foregone Flavors of France

16 Tuesday Apr 2013

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Food, Interviews

Tags

A la Recherche du Temps Perdu Marcel Proust, A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Adict, Berowra Waters Inn chef Gai Billson Australia, Bidding, Capital by John Lanchester, Charente, Chronicles of Old Paris, comme il faut, Côte d'Azur, expatriate literature in France, Federico Fellini, France, French cuisine, French food, Fumée d'Opium by Claude Farrère, George Lucas, HarperCollins, HarperPerennial, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, J.G. Ballard, John Baxter, Josef von Sternberg, King Vidor, la politesse, Luis Bunuel, Morphine by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest, Museyon Guides, My Lady Opium, National Public Radio's All Things Considered Outer Space Awaits: A sic-fi escape to the stars, Normandy, Paris, Paris Writers Workshop, Provence, Publishers Weekly John Baxter, Remembrance of Things Past / In Search of Lost Time Marcel Proust, Robert De Niro, Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, The God Killers, The Hermes Fall, The Last of the Wine John Baxter, The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, The Paris Men's Salon, The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, Thomas Atkins, Tour d'Argent Paris, UNESCO French gastronomic meal, Vacherin cheese and Passe Crassane pears, We'll Always Have Paris, Woody Allen

Share it

(French) John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is author of the memoirs The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, and The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, published in February 2013. A native of Australia, he lives with his wife and daughter in Paris, in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

(French) John Baxter is an acclaimed memoirist, film critic, and biographer. He is author of the memoirs The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, We’ll Always Have Paris, and The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France, published in February 2013. A native of Australia, he lives with his wife and daughter in Paris, in the same building Sylvia Beach once called home.

Since moving to France, John has published biographies of Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel, Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas, Josef von Sternberg, Robert De Niro and the author J.G. Ballard, as well as five books of autobiography, including A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. His most recent books are Chronicles of Old Paris and The Paris Men’s Salon, a selection from his uncollected prose pieces. John’s translations of Morphine, by Jean-Louis Dubut de la Forest and Fumée d’Opium, by Claude Farrère, have also been published by HarperCollins, the latter as My Lady Opium.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the internet in search of new acquisitions.

John has co-directed the annual Paris Writers Workshop and is a frequent lecturer and public speaker. His hobbies are cooking and book collecting (he has a major collection of modern first editions). When not writing, he can be found prowling the bouquinistes along the Seine or cruising the internet in search of new acquisitions.

In 1974 John was invited to become a visiting professor of film at Hollins College in Virginia, U.S.A. While in the U.S.A, he collaborated with Thomas Atkins on The Fire Came By: The Great Siberian Explosion of 1908, a highly successful book of scientific speculation, and wrote a study of director King Vidor, as well as completing two novels, The Hermes Fall and Bidding. (John Baxter: Facebook / Website )

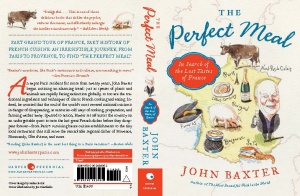

The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France

“Some of the most revered and complex elements of French cuisine are in danger of disappearing as old ways of agriculture, butchering, and cooking fade and are forgotten. In this charming culinary travel memoir, John Baxter follows up his bestselling The Most Beautiful Walk in the World by taking his readers on the hunt for some of the most delicious and bizarre endangered foods of France.” – HarperPerennial

“A spicy, humor-filled accounting of the culinary and literary history of a nation defined by its gastronomy…This is one of those delicious books that tickles the psyche, seduces the senses, and effortlessly enlarges the intellect simultaneously.” – Publishers Weekly

INTERVIEW

The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France

AWP: Why is now the right time to publish your book, The Perfect Meal? Did you feel a need to share a particular time and place in the style of today?

JB: In 2010, UNESCO declared the French “gastronomic meal” or repas an aspect of the “immaterial heritage of humanity,” and thus to be treasured and protected.

In itself, the decision wasn’t so surprising—Mexican food and the Mediterranean diet had been honoured earlier in the same way.

However I found it ironic.

Tacos and tortillas are common these days, even in France, and the Mediterranean cuisine of olive oil, tomatoes, garlic and fresh herbs is even more widespread. But the kind of meal UNESCO described—a formal dinner for more than ten people, usually to celebrate a wedding, retirement or the conferring of an honour, with multiple courses, wine, an aperitif before the meal, a digestif after, and toasts between each course—barely existed, at least in the big French cities like Paris, Lyon and Bordeaux. City restaurants no longer possessed the space, the staff or the expertise for such elaborate meals.

I decided to see if this traditional cuisine still existed somewhere in what is known as la France profonde—deepest France. As a symbol of the kind of feast honoured by UNESCO, I chose the roasting of an entire ox or steer. This was once a fairly common occurrence, but now it’s almost unknown. To find and attend an ox roast would prove that the French repas was still alive and well somewhere, if not in the cities. And as The Perfect Meal describes, I succeeded. The book ends with my wife Marie-Dominique and me sharing a roasted ox with five hundred other people in a field in Picardy.

AWP: You went on a quest to taste the last great French dishes before they disappeared forever—from Paris’ surviving haute cuisine establishments to the tiny local restaurants that still serve regional dishes of Provence, Normandy, and Côte d’Azur. These are such different regions of France—why did you decide to write about them together?

JB: It wasn’t simply the individual dishes that had disappeared from French city life but the tradition of the repas: the coming together of a family or group to celebrate a shared experience, like the American Thanksgiving or the British Christmas.

Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas described the experience of marrying into an old French family in which, because most of its members were writers, painters or academics, nobody could cook. As a result, I, an Australian with no natural connection to this great tradition, ended up re-affirming it by cooking Christmas dinner for up to twenty. That still seemed to me an enormous irony, and one worth exploring further.

AWP: What did you like best about each region?

JB: The surprise was more collective than individual. I learned that, when one turns off an autoroute and drives into the countryside, one steps back a century or more. Life moves more slowly there. People are more respectful of ritual and custom.

This applies to food as well. Country restaurants, with no worries about high rents, can cater to large parties. There are church halls big enough to accommodate banquets, often staged by the town itself. Nothing in Paris or Lyon quite approaches an aioli in Provence, where an entire village sits down to steamed fish and vegetables accompanied by aioli (garlic mayonnaise) or a sardinade, where they gather at long tables in the town square to feast on fresh grilled sardines.

AWP: What is it about France and food?

JB: Each nation has its way of “keeping score,” of establishing and demonstrating where a person stands in the pecking order. In some, it’s owning more and better objects: houses, cars, boats. Some assess relative value by signs of “class:” a different accent, better education, a uniform or a role in public affairs. Still others grade a person according to family background—the older the name and fortune, the more distinguished.

In France, food is one way of “scoring” a person. Traditionally, only aristocrats ate meat. Peasants got by on grains and roots. If they had meat, it was game, usually fat or tough. Their bread was heavy and dark, made from rye or millet, not wheat. That’s why, if the French say of someone “he eats meat every day” or “he eats white bread,” it signifies material success, the equivalent of being “on the gravy train.”

Because of this tradition, the richer and more distinguished a family, the more sparse and “refined” its food. Fatless veal fillet, a little mashed potato, green beans, a good wine, a little camembert or brie…this is the typical meal in the best houses. Robust soups and stews, sausages and the riper, smellier cheeses show you are still a peasant at heart.

AWP: During your research for The Perfect Meal, where wouldn’t you go? What cuisine wouldn’t you try?

JB: Obviously I couldn’t eat in every region of France; there would be no time left to write, and my system would have collapsed before the job was completed.

I promised myself that I would visit the four corners of France, from Picardy and Normandy in the north to both ends of the Mediterranean coast. Paris was familiar territory, and as we have a house in Charente, on the Atlantic coast, I already knew that cuisine.

I limited myself further by planning a “perfect meal” using the dishes I discovered. The meal might never actually be served, but the menu would be included in the book, along with some recipes, so that readers could recreate at least some of my finds in their own homes.

In each case, I also wanted to visit the area with a friend, someone to give a detached perspective on what we ate. This took a little organizing, and the availability of individuals dictated where and when I travelled. For example, a friend invited me to spend a few days in his house in the mountains above Cannes and Antibes. It was too good an opportunity to miss, and inspired one of my favourite chapters. But it meant I never got to Alsace, on the border with Germany, to sample its choucroute and sausages. I’m saving that for another book.

No dish was excluded just because it sounded repellent. I even sampled lamprey, a kind of eel/fish/worm that’s cooked in a sauce of its own blood (definitely not part of my menu). Some dishes, though delicious, didn’t fit a formal meal. One was socca, a pancake made from chickpea flour, olive oil and water. I ate it with fingers, fresh from the oven, dusted with white pepper, in the market in Antibes. No way could it be served at table.

AWP: Are there things that you felt haven’t been said about French cuisine that you are trying to explore in your work now?

JB: I already knew that in France, food and social life are intimately entwined, but researching The Perfect Meal was a forceful reminder of the passage in the Bible that states,“Better a meal of herbs than a stalled ox where love is.” In other words, a simple meal eaten with friends and loved ones is better than the most lavish banquet.

WRITING

AWP: Your career has taken you from science fiction, crime fiction, and biography writing to arts journalism, radio, TV and as a professor of film to the world of autobiographic memoirs. What inspired you toward a life and career so dependent on words and the ability to communicate? What influenced this vision?

JB: I once asked the Italian director Mario Bava how he was able to make such effective horror films. He said simply, “I am a frightened man.” When he slept in a house alone, he scattered crumpled paper around the bed to warn if someone was creeping up on him.

In the same way, I was born timid. My childhood was disordered. We moved around a lot, and I made few friends. Reading and going to the movies were my escape. By my late teens, I’d overcome my timidity and nervousness around people, and found I had the skills to write, as well as what used to be called “the gift of the gab,” a flair to tell stories and to speak in public. Once I put them to work, I had a career.

AWP: As an expatriate writer living in Paris, where do you situate yourself in the realm of expatriate literature?

JB: Writers come to France for different reasons. Henry James and Edith Wharton came here in the 19th century because it was a habit of the rich of other countries to spend some time here, Paris being regarded as the epitome of good taste. They both enjoyed that life and found a subject in it.

The writers who relocated here after World War I were entirely different. Most, like Hemingway, Henry Miller, etc., were poor. To them, Paris was the place where, if one was determined to starve in a garret while making a reputation as an author, one could survive for longer than in any other civilized city.

The expatriates of the fifties and sixties, predominantly African American or “beats,” were mostly fleeing something: racial prejudice, anti-drug laws, Vietnam. They wrote in Paris but seldom about Paris.

When I came here in 1989, the expat community comprised mostly eager newcomers who’d fallen in love with the mythology of the twenties and thirties, and comfortably established professional writers, journalists and academics who mined French culture for an Anglophone audience. It pretty well remains that way today, except that the eager are more eager and the comfortable more comfortable.

AWP: Your work has won great recognition, in particular the acclaimed book, The Most Beautiful Walk in the World. How has this experience changed your world?

JB: Beautiful Walk didn’t particularly change my world. Other books have been even more successful: The Fire Came By sold millions, was widely translated, and filmed, and my biography of Robert DeNiro did very well. But it’s true that I’m better known around Paris because of Beautiful Walk. People even stop me in the street to say how much they enjoyed the book, and I have more clients for my literary walks than I can handle.

AWP: Your first novel, The God Killers, was published in 1969 in the U.S. and Britain. You began writing books on cinema, gangster and science fiction film genres. Who is considered the most important of the earlier writers in these genres? Why?

JB: National Public Radio’s All Things Considered asked me that question a while back, and I responded, at least as far as science fiction is concerned, with the following tribute to one of my preferred science fiction writers and his best novel. I don’t think I could improve on it: NPR.ORG (NPR: Outer Space Awaits: A sci-fi escape to ‘the stars’)

AWP: What contemporary cultural phenomenon(s) do you think each of them would be most interested in? What modern trend do you think each would love the most?

JB: Contemporary crime fiction is preoccupied with serial killers. I find most of the novels inspired by this theme as tediously formulaic as the stately home butler-did-it mysteries of the 1920s. Science fiction is in the doldrums. Fantasy rules that particular roost, a genre I’ve never enjoyed.

AWP: Your memoirs, The Most Beautiful Walk in the World, Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas, and We’ll Always Have Paris, have had a huge impact on Francophiles and travelers to France. What do you think it is about your books that make readers connect in such a powerful way?

JB: As I explain in Beautiful Walk, I began taking people on walks as part of the Paris Writers Workshop, which I co-directed with Marcia Lebre. It became clear very quickly that visitors didn’t want to be lectured. For want of a better phrase, they preferred to “hang out,” ideally with someone who could answer their questions but who mostly would introduce them to the city in a casual, almost subliminal way. They wanted a friend in Paris. I try to make my books as little like guide books as possible. Sometimes the best way to learn about a place is to stand still and look around—but really look.

AWP: A native of Australia, in 1990, you met your present wife, the filmmaker Marie-Dominique Montel, and relocated to Paris from Los Angeles where you worked as a screenwriter and film journalist. Some men and women are predisposed, each in their own way, toward France: through fantasy, family or a cultural context. Was this the same for you, and if so, how?

JB: I’m not sure this is true. I certainly was not predisposed towards France. Keen as I was to leave Australia, the place I wanted to live was Los Angeles. I was living there, quite happily, when I met my present wife, and followed her back to France, a country I knew hardly at all. I spoke barely a word of French.

Very few expatriates live like the French. I’m a rarity in having married into a French family. Most expatriates have partners of their own nationality. Many more are alone. Of these, the majority has come to France to Live the Dream. Once they find that of all European cultures, that of France is one of the least inclined to fantasy, they leave.

AWP: In addition to being a student of French history and culture, literature and cuisine; what French cultural nuances, attitudes, ideas or habits have you adopted? In which areas have you embraced a similar aesthetic?

JB: The French are extremely formal. Modes of address, styles of dress, and ways of behaviour are very important. It’s easy to give offence, to say or do something that is pas convenable: inappropriate. La politesse is an important concept. Most situations are dominated by the rule of comme il faut—the way things should be. I learned this through trial and error, then found I rather enjoyed the precision of it. There’s an element of the game in doing or saying the right thing, and nobody plays it better than the French. One understands how they became great diplomats and why French is the language of diplomacy.

AWP: Tell me about your cooking and eating habits and traditions.

JB: Hard to answer, since a meal consists of numerous ingredients, only some of which are food.

My first meal at the Tour d’Argent certainly stands out. The room looks out over the Seine, a spectacular view at night. We ate duck—the specialty—preceded by lobster ravioli in a foie gras sauce.

In Australia, one of the finest restaurants was Berowra Waters Inn of chef Gai Billson. It was as impressive for its location and design as for the food. The building was by Pritzker Award winner Glenn Murcutt. One arrived by boat across a river, or by private float plane. The menu included stuffed pig’s ear with sauce ravigote and the skin of a goose neck stuffed with duck forcemeat and served with an orange sauce.

Of meals I’ve cooked, I remember lunch for a number of British publishers and agents who had come to Paris for the launch of We’ll Always Have Paris. I did slow-boiled beef in a very thick sauce, a mash of potatoes and celery root enriched with egg yolk and cream, followed by a gooey Vacherin cheese and fresh Passe Crassane pears—one of the classic duos of French cuisine, possible only during a few weeks of the year when the pears are in season.

AWP: Describe your own “Paris.”

JB: We’re fortunate in owning an apartment in the centre of the city. From our terrace, we can see both Notre Dame and the cathedral of Sacre-Coeur on the summit of Montmartre. The Luxembourg Gardens are just five minutes’ walk away.

So we live, in effect, in the equivalent of a five-star hotel suite. That alone makes living here a constant delight. I can look out each morning at the sun rising behind the towers of Notre Dame, walk through the Luxembourg to Montparnasse, passing Gertrude Stein’s old apartment, and have lunch at La Coupole, with all its associations with Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Man Ray, Dali, Aragon and Kiki of Montparnasse. Our building itself is a literary site, since Sylvia Beach lived here when she ran Shakespeare and Company, and was visited by all the greats of her day.

AWP: Name the single book or movie, work of art or music, fashion or cuisine that has inspired you.

JB: A la Recherche du Temps Perdu (in English, Remembrance of Things Past), or In Search of Lost Time, by Marcel Proust.

AWP: What is the latest book you read? Would you recommend it?

JB: At the moment I’m in the middle of John Lanchester’s Capital. So far it’s absorbing. I lived in London for fourteen years, so there’s a certain poignancy for me in his picture of the city’s middle- to upper-class society collapsing inexorably in a slow-motion avalanche of greed, prejudice, stupidity and malice.

AWP: Your passion for life is extraordinary. What’s next?

JB: My grandfather was a soldier here during World War I, so I’ve written a book about his experiences, and the changes that eradicated the belle epoque and ushered in les annees folles. It’s called The Last of the Wine. Harper Perennial will publish it to coincide with the 2014 centenary of WWI. I’m also planning a follow-up to The Most Beautiful Walk. And Chronicles of Old Paris has sold so well that Museyon is discussing Chronicles II.

John Baxter: Facebook / Website

SELECTED BOOKS BY JOHN BAXTER

The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France. Harper Perennial, 2013

Amazon / IBookstore / Barnes&Nobel / INDIEBOUND / Books-A-Million

The Most Beautiful Walk in the World: A Pedestrian in Paris. Harper Perennial, 2011

Chronicles of Old Paris: Exploring the Historic City of Light. Museyon Guides, 2011

Immoveable Feast: A Paris Christmas. Harper Perennial, 2008

We’ll Always have Paris: Sex and Love in the City of Light. Harper Perennial, 2006

A Pound of Paper: Confessions of a Book Addict. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2005

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® blog, French Impressions: Alice Kaplan – the Paris years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, on the process of transformation. Author and professor of French at Yale University, Ms. Kaplan discusses her new book, Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis, and the process of transformation. By entering into the lives of three important American women who studied in France, we learn how their year in France changed them and how they changed the world because of it. (French)

French Impressions: Anne Fontaine’s white shirts and the color of happiness. Anne Fontaine, a Franco-Brazilian fashion designer, entrepreneur, businesswoman and philanthropist, known as the “queen of the white shirt,” brought new faces and unforeseen levels of diversity to the fashion industry. Thanks to her, the white shirt is now definitely a staple on women’s wardrobes as a key piece. Anne shares her rise in the industry and 2011 launch of The Anne Fontaine Foundation, which is committed to the reforestation of the Brazilian rain forest. (French)

French Impressions: Brooke Desnoës on dance, the finest expression of freedom. Brooke Desnoës discovered dance as a student of Sonia Arova, a former partner of Anton Dolin of the Royal Ballet and in 1987, after graduation from high school, joined the Scottish Ballet under the direction of Alexander Bennet. In 1990, she obtained a diploma as a professor of classical dance, while dancing in the Georgetown Ballet in Washington D.C. In 1997, Brooke returned to France and founded the Académie Américaine de Danse de Paris.

86 Classic French films to watch again and again. French woman Bénédicte Mahé believes that to better understand French pop culture and French people you may meet, you need to have some notion of cinematographic culture. She shares with us important French films (mainly from the 1990s and 2000s) that will help you accomplish just that. (French)

Ballet Flats in Paris: And God made Repetto, by Barbara Redmond who shares what she got from a pair of flats purchased in a ballet store in Paris; a feline, natural style from the toes up, a simple pair of shoes that transformed her whole look. Including the vimeos “Pas de Deux Coda,” by Opening Ceremony and “Repetto,” by Repetto, Paris. (French)

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2013 John Baxter. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com