French Impressions: W. Scott Haine on café culture in Paris, Italy and Vienna

15 Tuesday Sep 2015

A Woman’s Paris™ in Book Reviews, Interviews

Tags

No tags :(

Share it

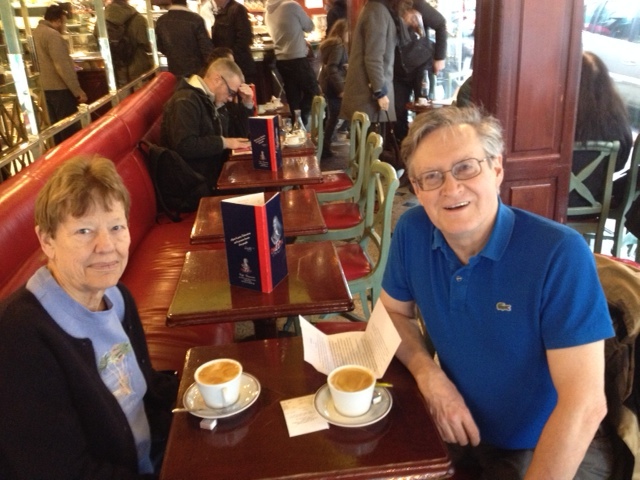

Scott Haine, professor and historian of food and sociability at the College of San Mateo, CA, was educated at the University of California, Berkeley (B.A.), and the University of Wisconsin at Madison (M.A. and Ph.D). Professor Haine has published widely on the history and culture and customs of 19th- and 20th-century France. His first book, The World of the Paris Café: Sociability among the French Working Class, 1789-1914 (Johns Hopkins University, 1998) investigates what the working-class café reveals about the formation of urban life in 19th-century France. His second book, The History of France (Greenwood Press, 2000) is a concise narrative that brings to life the compelling history of this fractious and fascinating country. Culture and Customs of France (Culture and Customs of Europe)(Greenwood Press, 2006), his latest book, is a thorough narrative of the glories that France continues to offer the world.

Scott Haine, professor and historian of food and sociability at the College of San Mateo, CA, was educated at the University of California, Berkeley (B.A.), and the University of Wisconsin at Madison (M.A. and Ph.D). Professor Haine has published widely on the history and culture and customs of 19th- and 20th-century France. His first book, The World of the Paris Café: Sociability among the French Working Class, 1789-1914 (Johns Hopkins University, 1998) investigates what the working-class café reveals about the formation of urban life in 19th-century France. His second book, The History of France (Greenwood Press, 2000) is a concise narrative that brings to life the compelling history of this fractious and fascinating country. Culture and Customs of France (Culture and Customs of Europe)(Greenwood Press, 2006), his latest book, is a thorough narrative of the glories that France continues to offer the world.

In 2013, Scott presented to critical acclaim at the Western Society for French History his paper Group infusion: Crowd Culture Revealing the origins of Simone de Beauvoir’s café life and the entry of France into WWII. He is currently at work on a new project on cafés during the period 1934-1946 and writer Simone de Beauvoir and her intellectual involvement in Paris during WWII.

Scott is a member of The Society of French Historical Studies and the online branch of this organization, and of H-France, an organization of scholars interested in French history and culture. He teaches online at The University of Maryland University College, as well as online and face-to-face in the San Mateo Community College District just south of San Francisco, CA. Scott now lives on the San Francisco peninsula during the summer when teaching face-to-face in Passaic, NJ, and in Paris. For more information, visit: shaine@aol.com

The cafe is not only a place to enjoy a cup of coffee, it is also a space—distinct from its urban environment—in which to reflect and take part in intellectual debate. Since the eighteenth century in Europe, intellectuals and artists have gathered in cafes to exchange ideas, inspirations and information that has driven the cultural agenda for Europe and the world. Without the café, would there have been a Karl Marx or a Jean-Paul Sartre?

The cafe is not only a place to enjoy a cup of coffee, it is also a space—distinct from its urban environment—in which to reflect and take part in intellectual debate. Since the eighteenth century in Europe, intellectuals and artists have gathered in cafes to exchange ideas, inspirations and information that has driven the cultural agenda for Europe and the world. Without the café, would there have been a Karl Marx or a Jean-Paul Sartre?

By revealing how the café operated as a unique cultural context within the urban setting, this volume demonstrates how space and ideas are connected. As our global society becomes more focused on creativity and mobility, the intellectual cafes of past generations can also serve as inspiration for contemporary and future knowledge workers who will expand and develop this tradition of using and thinking in space.

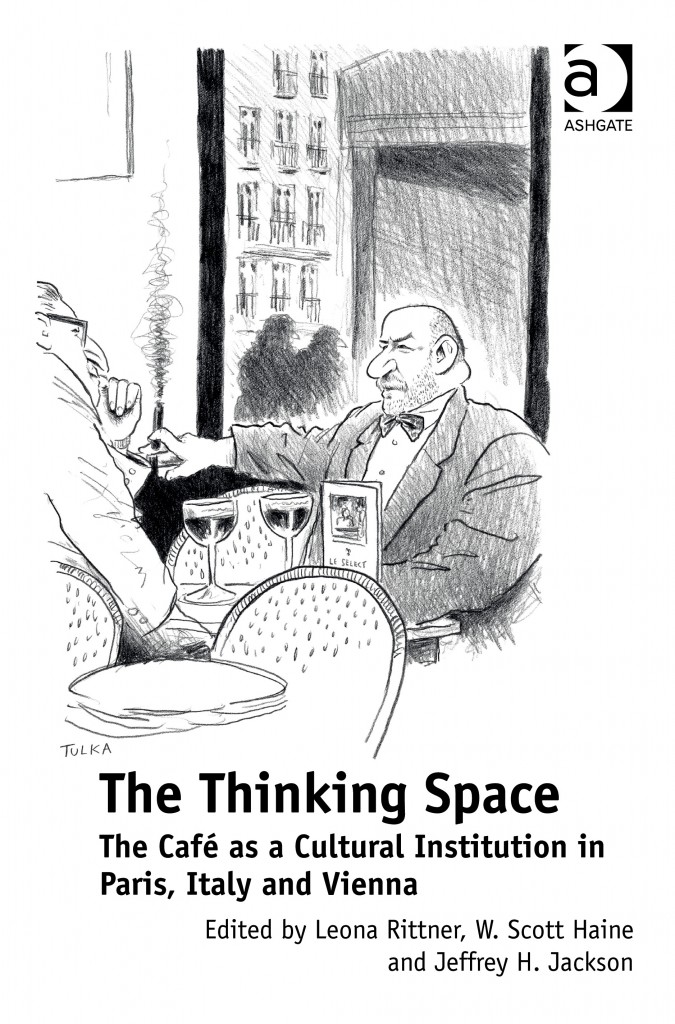

Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna (Ashgate Publishing Limited, England; 2013) edited by Leona Rittner, W. Scott Haine and Jeffrey H. Jackson. (Publisher’s note: Leona Rittner, who sadly died in 2010, was an independent scholar based in New York and published widely on French and Italian literature.) For information, visit: Ashgate History’s Profile Twitter / Purchase

Praise for The Thinking Space

“Across this collection, what emerges is that the café is a site where we can begin to understand not just the relationship between solitude and sociability across time, but also the relationship between speech and place; between speakers and overhearers; between national identity and race; between occupying forces and the occupied; between the elites and the masses. What is hopefully apparent, then, is that while this collection will appeal primarily to scholars of café and literary scenes, it also touches upon ideas of wider interest in historical geography.” – Journal of Historical Geography

Subscribers, The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna. A $124.95 value. Free book giveaway to one subscriber ends September 15, 2015.

Free Subscription: Join our thousands of followers to receive your copy of our Readers’ Choice: 253 Books About France, including books about Architecture, Interiors and Gardens; Arts; Biography; Children; Culture; Fashion; Food and Wine; Memoir; Mystery; Novel; Science; Travel; and War, along with email notifications of new posts on the website.

Once subscribed, you will be eligible to win—no matter where you live worldwide—no matter how long you’ve been a subscriber. We never sell or share member information.

Excerpt: “The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna (Excerpt, Part One) published on A Woman’s Paris®.

Excerpt: “The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna (Excerpt, Part Two) published on A Woman’s Paris®.

INTERVIEW

The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna

“The stage of mental comfort to which they had arrived at this hour was one wherein their souls expanded beyond their skins, and spread their personalities warmly through the room. In this process the chamber and its furniture grew more and more dignified and luxurious; the shawl hanging at the window took upon itself the richness of tapestry; the brass handles of the chest of drawers were as golden knockers; and the carved bed-posts seemed to have some kinship with the magnificent pillars of Solomon’s temple.” ––Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles

AWP: As an editor of The Thinking Space. What inspired you to write this book?

SH: Leona Rattner, scholar of French and Italian literature, wrote back in 1998 or so that she was gathering together a volume on the cultural role of cafés. She had seen my book, The World of the Paris Café: Sociability Among the French Working Class, 1789-1914, and requested a contribution. Overtime, I joined the project as an editor. Leona also asked Jeffery H. Jackson, a J.J. McComb Professor of History at Rhodes College, to contribute to her publication, and later I invited him to become another editor. Jeffrey proved to be key in getting a contract with Ashgate Publishing for this book. He is a brilliant, intellectual entrepreneur, which is vital in these times of zealous publishing.

AWP: You entrench your work in a different part of Paris’ past, taking stock of the café scene and mapping the transformation from a proletariat community to new forms of sociability and democratic expression. What challenges did you encounter, and how did you unfold the story you wanted to tell?

SH: A great observation linking my long-standing study of 19th-century working class cafés. Here I refer to what I just cited and that is noted in your superb introduction to my new work on intellectual cafés. The tentative title of my new book that I am co-authoring with Donna Evleth is The World of the Paris and French Café: Sociability and Strategy during Depression and War, 1934-1946. I consider this in the introduction to The Thinking Space regarding my thesis on the subject of anonymity as being key to working class sociability in cafés that, in many ways, set the tone for all drinking establishments. Within The Thinking Space, I include additional factors on the general café atmosphere in my article on Jean-Paul Sartre, one of the leading figures of 20th-century French philosophy and Marxism. In my upcoming book on Paris cafés, researcher and writer Donna Evleth and I reflect on the meeting of

Communist cells in cafés between World War I and World War II, when modern communism was developed and diffused around the world. In my view, I have not yet elaborated fully on this account: cafés, in reality, had a golden age – in terms of intellectuals, writers, and artists – roughly between 1890 and 1950.

These dates bracket a point in time when working class drinking declined, although contemporary media of that time had not yet taken hold of the daily life of the average Parisian. One theory in my upcoming book is that cinema did not detract from café life as much as one might expect. In my new work, I will argue that it was the arrival of the automobile that becomes more ubiquitous before television, which set the café into decline as it became the living room of much of France.

In The Thinking Space, ironically, its Sartre’s theory of how café sociability could overlap with social movements; a postulation that was never developed in his own magnum opus on social movements, The Critique of Dialectical Reason, or by the Communist Party – nor did Sartre, in fact, try to elaborate on this theory himself.

AWP: During your research for The Thinking Space, what aspect of café life in Paris wouldn’t you include?

SH: In The Thinking Space, I focused mainly on intellectuals and writers, and not on the social and economic conditions. I studied much of the secondary literature on intellectual and artistic cafés, especially the work of Gerard Georges Lemaire, who has been a great pioneer in the study of Europe cafés. Leona Rattner’s move to get Lemaire on board was brilliant, and it was crucial to have her English language distillation of some of his key points.

AWP: What did café culture imply for writers, artists, philosophers, and political activists? Did its culture evolve gradually or in jolts running parallel to major political or artistic turbulence?

SH: This is a complex and difficult topic to research. A close study would be needed of virtually all writers, artists, and intellectuals to fully answer this question. Overall, substantial developments emerge with the first cafés in the Middle East and Europe, and with the fact that coffee drinking has always been associated with intellectual life and later with newspapers – and more recently with the Internet.

For Paris in the late 18th century, it was the creation of this intellectual café culture after its first apparition in the London of Addison and Steel, through the ferment of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and various artistic movements of the 19th century. However, during this era, cafés seem to have had a subordinate place to the salons, which were commonly associated with French literary and philosophical movements. Then, alongside WWI and WWII various scholars have asserted that these wartime watershed events saw cafés overtake the salons, but a much more detailed study will be needed to verify this.

AWP: At various points, café spaces in Paris have had a dramatic impact on intellectual history. What is it about café life that is central to the diffusion of artistic and philosophical needs?

SH: A wonderful, big question! This, truly, is at the center of café life. Indeed, one can argue that the French/Paris café from the early 18th century was a cradle for the development of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, romanticism, and on through modernism – particularly Charles Baudelaire. The French poet influenced a generation of poets and the responsibility art has to capture the ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis. In a future book on cafés and intellectual life, I will argue that it was with the emergence of Surrealism during the 1920s that the café, in reality, assumed a key and even “formal” role in French cultural history and throughout the world. André Breton, French writer, poet, and founder of Surrealism, held meetings in cafés, from his early years through the end of his life. Even Sartre and de Beauvoir did not achieve such formality; Guy Debord and his Situationist movement came close.

AWP: You speak about “group infusion,” and “crowd culture.” What is this notion and how did it jump cultural norms during the 20th century, in particular?

SH: Another great question about a highly complex subject! Gustave Le Bon, one of the authors of the notion of crowd psychology, thought cafés were a vital space where the masses were indoctrinated and influenced with bad ideas. Gabriel Tarde, another early French social psychologist, argued that the “little paper” (in short, a cheap mass produced circulation newspaper), and “the drink,” “alcoholized the heart.” (Note role of beer halls and cafés in rise of Hitler in biographies such as those by Joachim Fest, German historian and leading figure in the debate among German historians about the Nazi period). The late 19th and early 20th centuries were the olden age of cities, cafés, newspapers, and cinemas across the world.

In recent history, there seems little connection between cafés and the “occupy” movement. Perhaps this was one of its weaknesses and why it has not returned.

AWP: How important was café habituation in France for crafting opinion and framing political and arts criticism?

SH: As I comment in my introduction to The Thinking Space, students of café life have shown that multifunctional venues have become a combination office, newspaper room, living room, and work space. Simone de Beauvoir explains in her reflection on travel across the United States, America Day By Day (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1948) that the interactions and stimulation of café life keep European writers in touch and creative in ways that American writers cannot attain at home. In short, this is the reason why so many American writers are one-hit wonders:

“To grasp what jazz means to a young American writer, you have to understand the stifling routine and deadly solitude of his days. In France, Spain, in Italy, in Central Europe, café life offers the intellectual and the artist the relaxation of comaraderie, emulation, and exciting conversation after his daily work. There’s noting like that here. Even gatherings like the one these evenings are very rare. Parties represent a social obligation to which they bow from time to time, but these are occasions for distraction more than for discussion, and it’s very rare that writers meet each other at such get-togethers. In Paris, literary life sometimes takes precedence over literature itself, which isn’t a good thing, but the absence of all literary life is still more debilitating. It is understandable that Hollywood and all the illusions of ease are dangerous temptations to the gifted writer, and it’s understandable that those who have difficulty creating become discouraged. It takes a great deal of asceticism and energy to “hold out” over the long haul. That is what explains a phenomenon that has long puzzled me—that after one very good book, or at least one that’s full of promise, so many writers are silent forevermore.” (Pp. 262-263).

AWP: Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986), French novelist, essayist, biographer, philosopher, and political activist – what did café culture imply for her?

SH: Just about everything! She was born above the Café de la Rotonde, and she and her sister dreamed of going there as children. Their father was a real upper class habitué and their mother a pious Catholic. An older cousin initiated de Beauvoir to the adult café, where she met Sartre and other philosophers getting their baccalaureate. De Beauvoir became a part of a generation of café habitués, along with writers like Marguerite Duras and Natalie Sarraute. (I detail Sarraute’s café frequentation and her work rituals in the introduction of The Thinking Space). From the 1930s through the 1950s, cafés were a key space for de Beauvoir to think, socialize, and write. After de Beauvoir and Sartre became international celebrities, they spent much of their time in cafés, including the basement bar at Hotel Pont Royal, a self-proclaimed literary hotel.

It was near the offices of the Gallimard publishers, who brought out their book along with many of the most prestigious authors of France. De Beauvoir and Sartre often lunched at La Couple in Montparnasse because the wait people would protect their prized habitués from paparazzi, tourists, and aspiring writers. La couple remained a real force in French cultural through 1980s in part due to two different spaces (both expensive and cheap sections that allowed various strata of the French cultural work force to interact) that often made contact going to and from the bathrooms (I owe this insights to Jim Haynes author and host at the center of Anglophone networks in Paris.) Since 1987 the Flo Group has run La couple, as well as many of the other classic cafés and bistrots of Paris. However, many believe the café is not as lively and integral to Parisian life as it was even in the early 1980s.

One question I also wish to explore is the decline of the intellectual/artistic café in relation to the end of the avant-garde.

AWP: How is the story of café life itself remembered and retold in French culture? What do they hide and what do they preserve?

SH: Great question! In many ways, The Thinking Space is the story of the hundreds of oral interviews I have done since 1989 on café life and its evolution. I wished to find out as many specifics about café life as I could, and I tried to interview people as old as possible to get a concrete sense of how café life transformed over the course of the 20th century. I had hoped everyone from café owners to habitués would have a stock of fascinating and personal stories. Alas, what I usually got was the following narrative: cafés, especially before WWII were great social spaces, aperitifs were king (they took the place of absinthe after its prohibition during Word War I). But after World War II, with the modernization of France – higher wages and better housing and modern consumer durables – the café lost some of its key functions for ordinary people. Refrigerators and espresso machines, for example, allowed cold drinks and good coffee to be found at home. Television provided an alternative to café sociability. In general the cinema and radio did not have as much of impact. Instead, I argue that both could be highly complementary to café life. Moreover the ongoing anti-alcohol campaigns of the French government (especially those during World War, in particular under Vichy, and continuing into the Fifth Republic of de Gaulle) meshed with a dramatic change in the consumption habits of the average French family. A shift occurred from daily small purchases of food and drink to a growing concern with saving for larger purchases like summer vacations or for consumer durables. Putting money aside for summer vacations emerged for the first time when the Popular Front government (1936-1938) instituted summer vacations with pay for the workers for the summer. The development of congés payés (paid vacations) inspired people to save for the beach in the summer rather than the apéro after work or after diner.

Naturally, after WWII and in particular from the late 1950s – with the growing pervasiveness of automobiles and the relatively tardy (late 1960s through 1970s) diffusion of television sets and then programming – we see cafés decline dramatically in numbers. To sum up a long complex story: over 500,000 cafés existed across France in 1938, to under 300,000 cafés by 1946, to 220,000 cafés by the late 1960s, to about only 33,000 cafés in 2015. We see an astonishing decline. Indeed, just Google French and Paris cafés in decline, and you will get a sense of what a common theme this has become.

Yet, I will also show that much of this decline is media hype. Cafés, even in much more limited quantities, remain a powerful force – both at the elite and the popular level – for the development and evolution of French culture.

AWP: How does the shift to a digital, fully open, and global marketplace play into modern day café life?

SH: The increasing ubiquity of digital media suddenly makes face-to-face interaction not a banality, as it has been traditionally, but a luxury. At a bar or table, people have a chance again to connect. As Pynchon notes in one of the masthead quotes in my introduction to visceral animal spirits in human beings in public places: Whether on savannahs in Africa, the cities of Egypt and Mesopotamia, India, or China people traditionally lived a public life. Philippe Aries, a student not only of the family and private life but also of public sociability, lamented from the post-WWII era until the time of his death in the early 1980s that human being were losing the sense of being public entities and not just private consciousnesses. As hunter-gatherers, especially sitting around fires at night watching the stars cross the skies, human being emerged as an especially mobile and sociable species. (Jack London makes this point in his anti-alcoholic polemic, John Barleycorn (1913).)

AWP: In a world that is becoming all the more serious and ferocious in its competition, is there a role for the café? Could it become, as we know it, obsolete?

SH: I think cafés will outlast bookstores, most department stores, and even specialty shops. People always need to eat and drink, to rest and refresh themselves, especially when they are on vacation. This is equally important for business trips: you need to acclimate to the local environment, to begin to feel grounded before any meeting. The café is as important a point of embarkation as an airport and a lot less chaotic. As I note in my introduction, Steve Jobs is merely the most famous of the hi-tech CEOs that believed that face-to-face, café-style, and spontaneous sociability best fostered creativity. We also see this again at the end of The Imitation Game when Alan Turning gets his big Eureka moment in a pub.

AWP: You write about tourists and cafés in Paris as a place of pilgrimage that one visits, like a museum. Do we have a secret hope of finding something there?

SH: Yes, absolutely. Unlike the formal space of a museum or library, a café is a place of purchase, conversation, and searching. There is always the hope that something magical will happen, especially for the tourist. For example, I have heard American tourists at sidewalk tables of the café Deux Magots saying that the street life one sees around this iconic café provides the best evening show in Paris.

WRITING

AWP: When you started writing The Thinking Space, did you have a sense of what you wanted to do differently from other accounts of café life in Paris?

SH: Systematically explore the life of writers and their lives in cafés to go beyond anecdote to get to sociability patterns, writing rituals, and marketing strategies. As I discovered, this study connects to a growing literature trying to unlock the dynamics of creativity amidst a globalized world where with so much of the world’s intellectual and technological elite always on the go, a welcoming café from Shanghai to San Francisco to Stockholm becomes a vital venue for contact, preparation, meetings, and follow-up.

AWP: You have a shrewd grasp of how common culture works, often in strange ways. How did you come to it?

SH: By triangulating between academic, cultural, and participant observation sources. Patience and persistence are keys. I wish to explore the hinge between daily life, and events of either a ludic or political nature in cafés the hinge between public and private life, the home, and the street.

AWP: What things do you feel haven’t been said about café culture in Paris that you are trying to explore in your work now?

SH: Café life, like life in general, is ever=changing and you never know what will come next! This is not like a business office or a family home. It is a bit of both, with more permanence than the milling of a city street or the endless information of the Internet. What is fascinating is the intersection of the Internet and cafés. Most cafés have websites, and I am sure increasingly will have blogs and be sites of flash crowds.

Life will certainly become more digital, with even driving being taken over by computers. In this case the café will be one of the last places for spontaneous face-to-face sociability.

ART OF LIVING

AWP: Name the single café in Paris that has inspired you. Why?

SH: I do not believe I mentioned my “home base” in Paris. For over a decade, I have gone to Le Falguière, a café-bar at 129 Rue de Vaugirard, rue by Fred. It attracts a fascinating, diverse, and always-changing clientele (that usually includes Fred’s friends from all stages of his life). For the most part, it is just an ordinary café, but one that has philosophers, poets, and distinguished retirees among its patrons. Almost certainly as the medical institutions proliferate around the Pasteur Institute, there will be more scientists such as Phineus, now in San Diego at the Salk Institute who often worked around the clock, but took breaks and celebratory meals (with his family) at the café.

AWP: What’s next?

SH: I will continue to work on A Cultural History of Alcohol 1750 to 1850, The World of the Paris Café during World War II, and The Café in a Century of Urban and Cultural Transformation 1914 to 2014. But I have also become entranced by the social cultural and intellectual affinities of Simone de Beauvoir and Nelson Algren in both their lives, their writings, and in their complex and enduring relationship. Such as study gets to the heart of why intellectuals link up in both social and intellectual space. It also provides a window upon our increasingly global world as one of their most important affinities was traveling and exploring foreign countries cities together. They produce a fascinating joint journal of their trip down the Mississippi and to Mexico that should be published one day. Much of what I whish to focus upon in all of these publications comes out well in the lives of these two legendary intellectuals.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED BY W. SCOTT HAINE

Simone de Beauvoir American Day by Day, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) This multilayered book not only provides an fascinating cross cultural insights into socializing, drinking, and creating but also illuminates post-World War II American society in 1947 through the lens of Existential philosophy.

Acknowledgements: Lee Murphy, student of new media communications at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities and copy editor for A Woman’s Paris.

You may also enjoy A Woman’s Paris® post Whistle Stop Coffees: Flore der Agopian on Cafés in Train Stations in Paris. “When I walk inside a train station in Paris,” writes Parisianne Flore, I always feel like I’m taking a journey back in time; an out-of-reality experience immortalized in countless French and American films: Nikita, Les Poupées Russes, Mr. Bean’s Holiday, and Ocean’s Twelve, to name a few.” Flore writes about Gare Montparnasse, Gare de Lyon and Gar du Nord and the cafés and restaurants you will find there—from the famous Le Train Bleu and Terminus Nord to Paul, the boulangerie café founded in the late 19th century, and now a worldwide success.

Hotspots and Hot Chocolate: Student Cafés in Paris by Parisian Flore der Agopian. The Left Bank has always been “the place to be” for intellectuals, artists and students. By strolling through the famous Latin Quarter, which attracts many students from the whole of France, you can feel the lively, bustling atmosphere created by the presence of the famous universities, such as La Sorbonne. Follow Flore as she visits the seven most famous student cafés in Paris.

Café Culture in Paris, by Parisienne Flore der Agopian. The café, writes Flore, is a pleasurable way of sitting unbothered for hours on end with a book, with friends, or jut watching all sorts of people coming and going. Le Café de Flore, one of the oldest and most prestigious in Paris, where you can meet or observe its famous clientele among the Parisians, tourists and waiters dressed in their black and white uniforms as if they were still in the 1920s. To Flore, Café de Flore is almost mythical, legendary—a real institution. (French)

Museum tearooms in Paris. Parisienne Flore der Agopian invites us to visit some of the most enchanting tearooms in Paris: Café du Musée de la Vie Romantique, its courtyard garden a step back into the 19th-century; Café Jacquemart-André, decorated and furnished in late 19th-century style; and La Flottille, in the garden of the Château de Versailles in front of the Grand Canal. Including a list of Museum tearooms, cafés and restaurants in Paris.

A Woman’s Paris — Elegance, Culture and Joie de Vivre

We are captivated by women and men, like you, who use their discipline, wit and resourcefulness to make their own way and who excel at what the French call joie de vivre or “the art of living.” We stand in awe of what you fill into your lives. Free spirits who inspire both admiration and confidence.

Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street, fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening. — Coco Chanel (1883 – 1971)

Text copyright ©2015 W. Scott Haine. All rights reserved.

Illustrations copyright ©Barbara Redmond. All rights reserved.

barbara@awomansparis.com